Shortly before each Grand Départ, the Tour de France’s promoter, Amaury

Sports Organisation, proudly trumpets figures demonstrating the grandeur

of its race. The Tour involves more than 30,000 gendarmes, firefighters and departmental officials, fuels 7,800 hours of live broadcasting in 190 countries, and reels in 12 million followers on social media.

Then there is the 10km-long publicity caravan – carnival floats travelling the route distributing pens, key rings, flags and caps sponsored by major international brands and known to most as the ‘junk train’. Coming behind that, is the 176-rider peloton, now including riders from Slovenia, Eritrea, Colombia, the United States, Australia, South Africa and Britain.

There are even some French riders in the Tour de France, although it’s almost 40 years since a home rider wore the coveted yellow jersey in Paris. Bernard Hinault, winner in 1985, will be 68 this year and his long wait for a successor continues.

This year’s Tour, which starts in Copenhagen next Friday, is expected to follow the usual pattern. There will be much sabre-rattling from the major

team leaders as the race begins, the French participants will huff and puff

and bag a stage win, here or there, but a better-paid and more talented

foreign rider will win the race overall in the end.

Meanwhile, the globalisation of the Tour is demonstrated not just by the

fact that the peloton’s biggest sponsors are not French, but also by other

anniversaries. This July marks 25 years since the first German winner, Jan

Ullrich, and a decade since Bradley Wiggins recorded a groundbreaking British success in the summer of the London Olympics. The explosion in

popularity of the Tour in Britain post-2012 inspired ASO to venture to Yorkshire for the least likely of Grand Départs in 2014. That then fuelled a brief spell promoting the Tour de Yorkshire men’s and women’s races, although both were lost to the ravages of the pandemic.

Ironically, despite the inability of the host nation to provide an heir to Hinault, the Tour’s global popularity continues to grow.

While ASO’s marketing of the race relies on sepia-tinted memories of past champions, Louison Bobet, Jacques Anquetil, Hinault et al – with no mention anywhere of cycling’s Voldemort, Lance Armstrong – its current champion, Slovenia’s Tadej Pogačar, is big on TikTok and Instagram, where he freely shows off his questionable rapping skills.

Pogačar, born in 1998, the year of the harrowing Festina doping scandal that almost brought the Tour to a halt and that further depressed homegrown talent, has already won two yellow jerseys and is the favourite to win the race overall again this year.

His team is sponsored by UAE Emirates and managed by Mauro Gianetti, one of the former riders from that disgraced pre-millennial era, whose past history of doping scandals has been conveniently swept under the carpet as the Tour’s Slovenian fanbase grows. Dwelling on the history of Pogačar’s backroom staff is discouraged, as is any questioning of how Slovenian cycling has risen to the pinnacle of the sport in so short a time. Scarred by the scandals of the recent past, nobody in cycling wants to be reminded of its economic fragility.

As the Tour’s internationalisation continues, the post-Armstrong makeover as gathered pace, although in France, reservations over globalisation remain. In an excellent new book, Le Fric, by Alex Duff, the relationship between the race and France’s institutions is also explored. On the one hand, the Tour wants to be big in America, the holy grail of sports marketing; on the other, chastened by the Armstrong experience, it has to be wary of the superbrands – Nike, Google, Coca-Cola – taking over an event that still sells itself as the personification of patrimonie.

Duff explores the intertwined relationship between the Tour, the traditional idyll of the summertime fête populaire, the French media and the State and explores the efforts made by ASO to repackage the race in the post-Armstrong era.

French winners may be hard to come by during July’s fête populaire but French presidents are ubiquitous, with messrs Chirac, Sarkozy, Hollande and Macron, all fully aware of the emotive power of the old race, regular VIP guests in the race director’s limousine.

When the pandemic caused the 2020 race to be postponed until September,

Macron was quick to defend the institutionalised popularity of the Tour. “When we talk about the French way of life, we are talking about our culture, our gastronomy, our conviviality and our great sporting events. The Tour de France is an absolutely exceptional event,” he said.

As long ago as 1968, after the social unrest that summer, Charles de Gaulle,

seeking to shore up his popularity, pointed to the staging of the Tour as a

return to ‘normality,’ however short-lived that proved. But in contrast with its global growth, the Tour remains something of a stranger at home. The French fanbase is largely male, pale and to many, stale. Eco-activists in particular have little time for the anachronistic, gas-guzzling juggernaut, the VIP helicopters, the logistics lorries and luxury team buses, chugging through the countryside.

In 2020 the mayor of Lyon described the Tour as polluting and lacking an environmental conscience, as well as being blind to the needs of gender diversity, something that is finally being addressed this July with the return of the women’s Tour de France, which has former professional rider Marion Rousse as race director.

There have been multiple calls for the race to reduce its carbon footprint and last year the race organisation stepped up its recycling programme and encouraged the use of plug-in hybrids among the convoy, rather than more traditional petrol and diesel vehicles. Then there are the accusations of both greenwashing and sports washing that are now hovering over the professional peloton. Pogačar’s UAE Emirates sponsor is one example but there are other sponsors in cycling – Bahrain, Gazprom, Kazakhstan and even Britain’s Ineos Grenadiers – that have been accused of using cycling as a smokescreen for more nefarious activities.

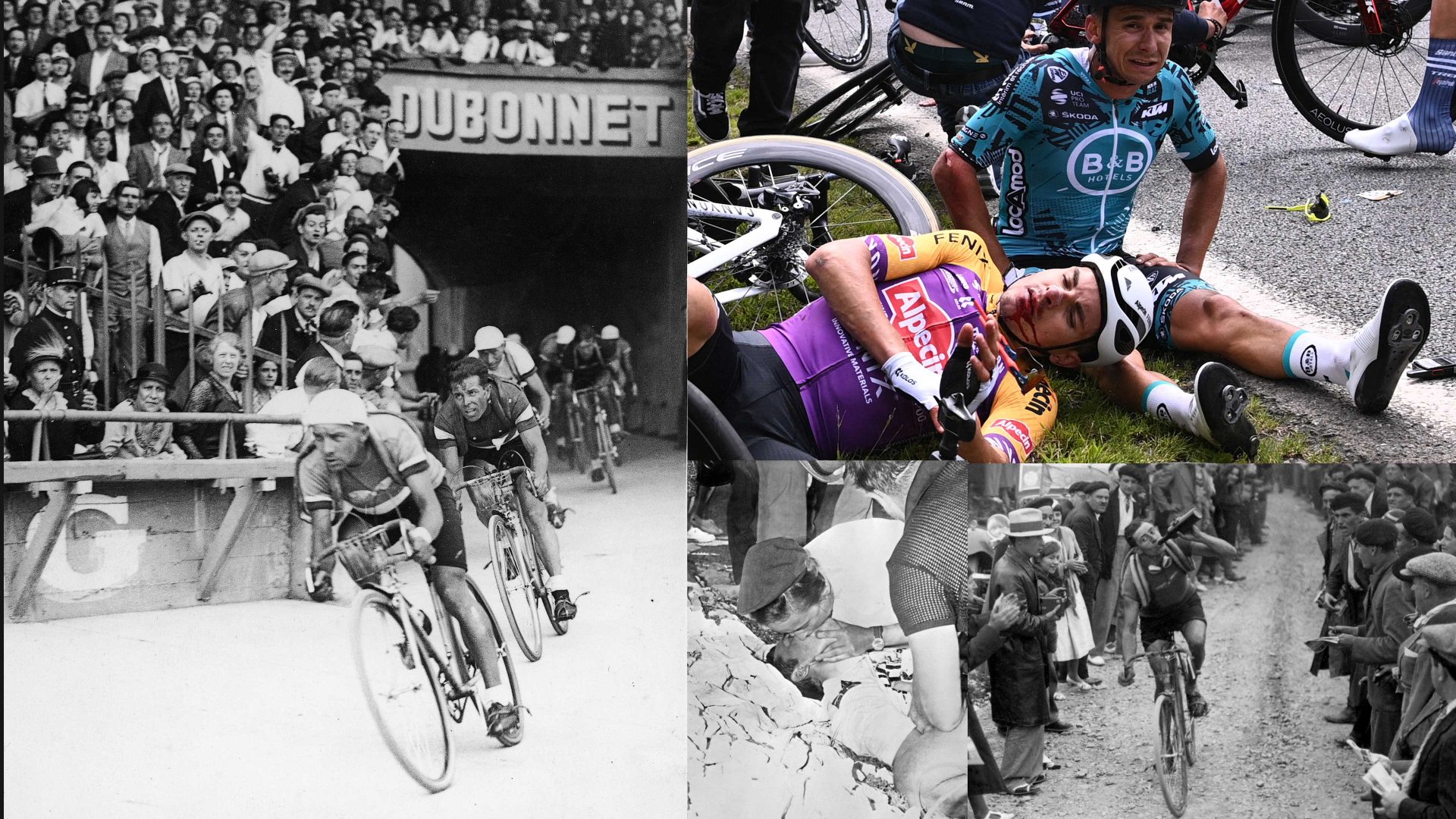

But what sells the Tour is its unapologetically gladiatorial quality. Unvarnished, brutal, even heartless, the culture of sacrifice and suffering has endeared it to millions. As long as that tradition of sporting voyeurism

continues, its future popularity seems guaranteed.

Jeremy Whittle is editor-in-chief of cycling magazine Stelvio

TIMELINE OF LE TOUR

1903-04

The Tour de France makes its debut as France’s longest cycle race. Maurice Garin wins the first two Tours, but his second win is wiped out when it is found he cheated by taking a train.

1910

For the first time, riders are sent over the “circle of death” in the Pyrenees. The first rider has to push his bike up the initial climb and accuses the organisers of being “murderers”.

1919

The yellow jersey is introduced for the rider who has the lowest cumulative time at the end of each stage. It is yellow because that was the colour of the pages of L’Auto newspaper, the race’s initial sponsor.

1929

Belgian Maurice De Waele wins despite being ill, thanks to help from his Alcyon teammates. Organiser Henri Desgrange is enraged and says: “My Tour has been won by a corpse”.

1930

Enraged by what he sees as trickery by the teams, Desgrange abandons commercially sponsored teams in favour of national teams. Trade teams returned in 1962.

1935

Spanish cyclist Francisco Cepeda becomes the first rider to die during a stage after he crashes descending the Col du Galibier near Grenoble – the eighth-highest paved road in the Alps.

1954

The first Grand Départ – start of the race – to take place outside France, in Amsterdam. The right to host the Grand Départ is highly sought after and it will be Copenhagen’s turn in 2022.

1967

British cyclist Tom Simpson, 29, collapses and dies during the ascent of Mount Ventoux. Amphetamine and alcohol use, as well as heat exhaustion, are said to have contributed to his death. Doping scandals will dog the race for years.

1991

Spain’s Miguel Induráin wins the first of five consecutive Tours. Three other riders have won five Tours: Jacques Anquetil and Bernard Hinault of France and Eddy Merckx of Belgium.

1995

Italian cyclist Fabio Casartelli, 24, dies after crashing during a descent of the Col de Portet d’Aspet in the Pyrenees. Some say that he would have survived the crash if he’d been wearing a helmet. The UCI cycling union makes helmets mandatory for professional races in 2003.

1998

French police raid team hotels looking for drugs after the Festina team is expelled for drug use. Riders stage a sit-down strike and stricter anti-doping measures are later put in place.

1999

US cyclist Lance Armstrong wins the first of seven consecutive Tours. He is stripped of his titles in 2012 after the US Anti-Doping Agency finds he used performance-enhancing drugs.

2021

A young woman waving a sign causes a massive crash during the first stage.

Germany’s Tony Martin is the first to fall, but dozens follow. Eight are injured and two riders withdraw.