Summer, 1986: I am backpacking across the United States, and a friend from Arizona takes me to see the Senate buildings in Washington DC. We make our way to the offices of Barry Goldwater, long-time senator for the Grand Canyon State, in the rather optimistic hopes of an unscheduled audience.

Sadly, Goldwater, serving his final months as a lawmaker, is out of town, and we leave his palatial suite, agreeing that it was worth a try. But in the corridor, we are greeted by what can only be described as a wave of kinetic energy: a group of men carrying clipboards and briefcases, a baritone phalanx led by an undoubted alpha male, six foot-plus, who, one can tell from his stride alone, is the guy in charge.

In what is not yet called a West Wing moment, they walk and talk, leaving the unmistakable sensation of power and assurance in their wake. This is the 43-year-old Joe Biden, senator for Delaware since 1973, who will run for the presidency for the first time the following year.

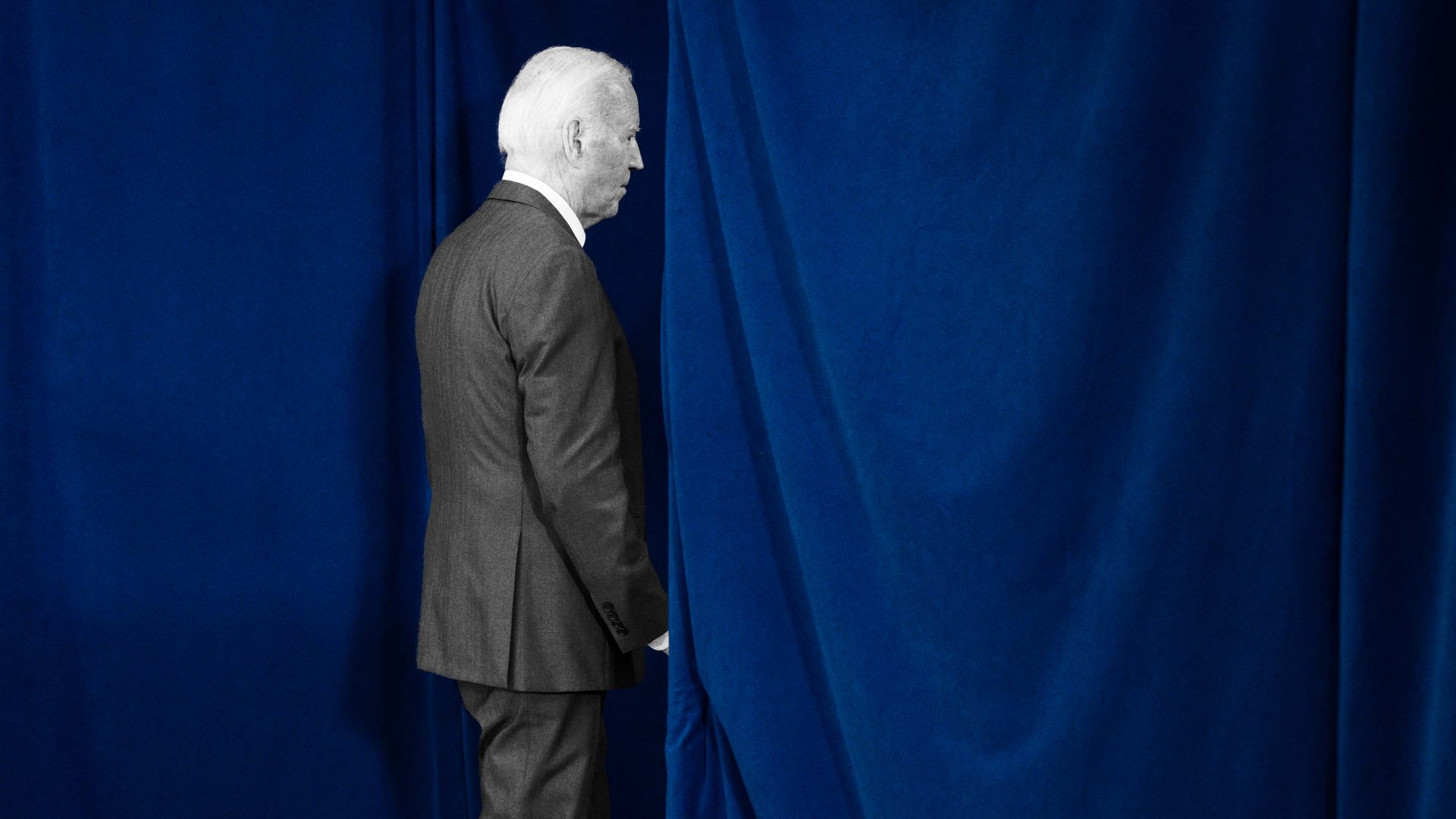

In the past few weeks, I have thought back to that moment often and reflected upon the pitilessness of time, as the 81-year-old Biden, enfeebled and flailing, has tried desperately to cling to power. On Sunday, after weeks of pressure from senior Democrats, he finally made his peace with reality.

And that, too, reminded me of Goldwater, who, on August 7, 1974, led a congressional delegation of senior Republicans to the Oval Office and convinced Richard Nixon that, if he did not resign, he would be impeached and convicted. The next day, the president quit.

The symmetries are not exact: Biden has committed no high crimes or misdemeanours, and will leave office on January 20, 2025, with a strong record as a single-term president, having devoted himself to public service since the age of 29. But – no less than Nixon – he has been strong-armed into his decision, in this case by senior Democrats and donors speaking in public and private, warning him that he faced a lonely electoral catastrophe if he insisted on running once more against Donald Trump in November. This was a velvet mutiny, with a sliver of steel in its heart.

It would be churlish to deny that, in the end, Biden put nation before party, and duty before vanity. He is a man who prizes his dignity, believes passionately in his capacity to turn adversity into triumph, and has always sensed a measure of snobbery in the attitude of the Democratic establishment towards the boy from Scranton, Pennsylvania.

Remember the famous exchange from The Lion in Winter (1968). Geoffrey: “My, you chivalric fool… as if the way one fell down mattered”. Richard: “When the fall is all there is, it matters”. It mattered greatly to Biden.

But it is important not to be sentimental about his sacrifice. He left it late; ridiculously late. The Democratic National Convention opens on August 19, and, in several states, early voting begins as soon as September.

His physiological fitness to serve a second term has been in serious doubt since (at the latest) February 2023 when he challenged the doubters to “watch me”. The problem is that they did.

Long before his disastrous debate performance at the CNN debate in Atlanta on June 27, his mental acuity and physical condition were a matter of national debate, opinion polls showing with ever greater clarity that the voters thought he was too old to run.

In February, he responded with fury to the verdict of special counsel Robert Hur, in his report on his allegedly unauthorised storage of classified documents, that the president was “a sympathetic, well-meaning, elderly man with a poor memory” – and therefore unfit to be prosecuted. In his inarticulate rage, he demonstrated that Hur’s judgment, however ruthless, was also correct.

After Atlanta, concern degenerated into crisis; every time Biden sought to resolve the problem, he compounded it. Whenever he said “anyway”, or “here’s the deal”, or “by the way”, you knew another cognitive car-crash was on its way and winced in anticipation.

Biden’s first act as an ex-candidate was to endorse Kamala Harris, who has a well-known taste for somewhat gnomic aphorisms and utterances. She often refers to “what can be, unburdened by what has been” (meaning that progress need not necessarily be thwarted by the weight of the past).

My favourite – also beloved by meme creators – featured in her remarks at a White House event in May last year. “You think you just fell out of a coconut tree?” she asked rhetorically. “You exist in the context of all in which you live and what came before you”. This has inspired her most fervent supporters to describe themselves as “coconut-pilled”. But it also happens to be true.

In politics, as in life, context is all. And there is no disguising the fact that Harris – or, indeed, anyone succeeding Biden as nominee at this late stage – is in receipt of the mother of all Hail Mary passes. A winning presidential candidacy usually takes at least two years to construct. Harris has just over three months.

The speed with which her principal rivals – Gretchen Whitmer, governor of Michigan, Josh Shapiro, her counterpart in Pennsylvania and Gavin Newsom of California – fell in line behind her was instantly interpreted as a de facto coronation. But these star players were not just acquiescing in the seemingly inevitable; they were also running for cover.

The Democrats are a deeply superstitious tribe and the turmoil of the past month has reminded them all too keenly of 1968, Lyndon Johnson’s decision not to seek renomination, and the ensuing mayhem at the party’s convention in Chicago – the very city hosting the DNC next month. LBJ’s vice-president, Hubert Humphrey, secured the nomination, but only messily, and went on to lose to Nixon.

As Norman Mailer wrote in his classic account of that gathering: “The last property of political property is ego, ego intact, ego burnished by institutional and reverential flame”.

Since the possibility of Biden’s departure from the race became real, the Democrat elite has been terrified that its convention would become a riot of competing egos, a crack-up in real time of the party coalition that he so meticulously assembled in 2020.

A faction of party strategists and opinion-formers, led by Ezra Klein of The New York Times, has argued for an open convention, a carnival of democratic discourse at which the party’s best and brightest could pitch for the favour of its 4,000 delegates. In this connection, they cited The Lincoln Miracle, Edward Achorn’s fine book about the 1860 Republican Convention, and the injunction to the assembly of Massachusetts senator, Charles Sumner, “to organize victory”.

As noble as this ambition might have been in principle, it never stood a chance in the cruel world of political reality. Still, Harris was absolutely right on Sunday to pledge that she would “earn and win” the nomination.

It is essential that, at this moment of all moments, the Democrat rank-and-file feel respected and honoured; that they be invited to minimise the turmoil that inevitably lies ahead, already referred to euphemistically by senior party figures as “a time of transition”.

I have long thought that Harris is an under-valued asset to her party, that her public performances since the overturning of Roe v Wade have shown that she retains the focus and steel of a prosecutor. She is livelier than Biden – but so, to be honest, is everyone else. She polls better than the president in battleground states, but not by much.

She stands at least a chance if she persuades her party and the electorate to believe in her as a candidate in her own right, rather than an understudy. She has to be relentlessly future-facing, and not repeat Biden’s mistake of captiously demanding acclaim for his record.

The voters she must win over in Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin don’t want to hear about the administration’s (undoubtedly impressive) legislative record. They need to be reassured about the cost of living, sound management of the southern border, house prices, the Democrats’ plan to restore order and decency to women’s reproductive health care.

They do not want to hear about the abstractions of “democracy”. But they may be receptive to a clear, specific warning about Trump’s explicitly authoritarian plans and the dark implications of the Project 2025 blueprint.

Americans like strong leaders, but they also hate having their rights taken away. In the gap between the two impulses lies the Democrats’ opportunity.

All the same: it would be idle to deny the scale of the task. Against expectation, Trump’s campaign – run by Chris LaCivita and Susie Wiles – is much the most formidable and disciplined of his nine-year political career. Within an hour of Biden’s announcement, a pro-Trump super-PAC had posted an attack ad on X, lambasting Harris for her complicity in all his alleged failings (“Kamala was in on it. She covered up Joe’s obvious mental decline. Kamala knew Joe couldn’t do the job, so she did it. Look what she got done: a border invasion, runaway inflation, the American Dream dead”).

This is only a taste of the political savagery to come. Ominously, the official campaign is devoting huge resources to what it calls “electoral integrity” – a euphemism for challenging the result if it goes against Trump. There has also been a sharp uptick in far right militia activity since the attempt on the former president’s life; while those that he calls the “January 6 hostages” languish in prison, new and better organised paramilitary groups are rising up across America.

We are all strapped into a high-speed rollercoaster ride called “Fate of the Free World”. Absurdly, it now seems an age since the attempted assassination of Trump in Butler, Pennsylvania, and the instantly iconic image of the bleeding former president raising his fist to the air and bellowing: “Fight!”

But – as senior Democrats admit in private – that horror bequeathed to the Republican nominee a convention in Milwaukee of almost surreal unity and veneration. There was much talk last week of “divine intervention”. Trump was hailed not as a regular nominee but anointed as an instrument of providence.

Not that every voter sees the race in such explicitly religious terms. Far from it, in fact. At least Trump is no longer coasting to victory against an opponent doomed by visible decline, the rage of Lear and a party at war with itself. At least now there is a fresh variable. Is America – still a patriarchal nation, stained by a history of racism – ready to elect a Black woman as its commander-in-chief?

Harris is going into the ring against an orange maniac who will do and say absolutely anything to get back into power. To say that she needs to bring her A-game, to the second presidential debate on September 10 and to everything else, is the mother of all understatements. Now that Biden has stepped aside, her candidacy is the worst option available to the Democrats – except for all the others.

What happens next matters profoundly to all who care about the American republic. But it will also have a serious impact upon the fate of Ukraine, the prospects of global action on climate change, the future of Nato, the risks of a trade war. We are all in on this one.

In 1968, Mailer, invited to address the protestors in Chicago, declared that “there is a beastliness in the marrow of the century”. It is hard to deny that this beastliness has survived and metastasised in our own.

In the coming months, in a presidential race that has defied prediction at every turn, we shall discover how grave our collective predicament truly is.