For nearly a quarter of a century, Benito Mussolini had a profound impact on the history of Italy and, increasingly, on the whole of Europe – indeed, through imperialist conquest and as the ally of Germany and Japan during the second world war, on the world beyond Europe. In Italy, he presided over a dictatorship that lasted for more than two decades. Before wartime fortunes rebounded in devastating fashion on the country, he enjoyed the backing of millions of Italians, and was idolised by many of them. In other countries in interwar Europe, not only those drawn to fascism but also many conservatives saw him as an icon.

He wanted war. Under Mussolini, Italy was involved in war in one form or another in the 1920s and 1930s in Corfu, Libya, Ethiopia and Spain. But when general European war, then world war came to Italy after 1940, it inflicted misery, suffering and devastation on the country and on the territory in Italian hands.

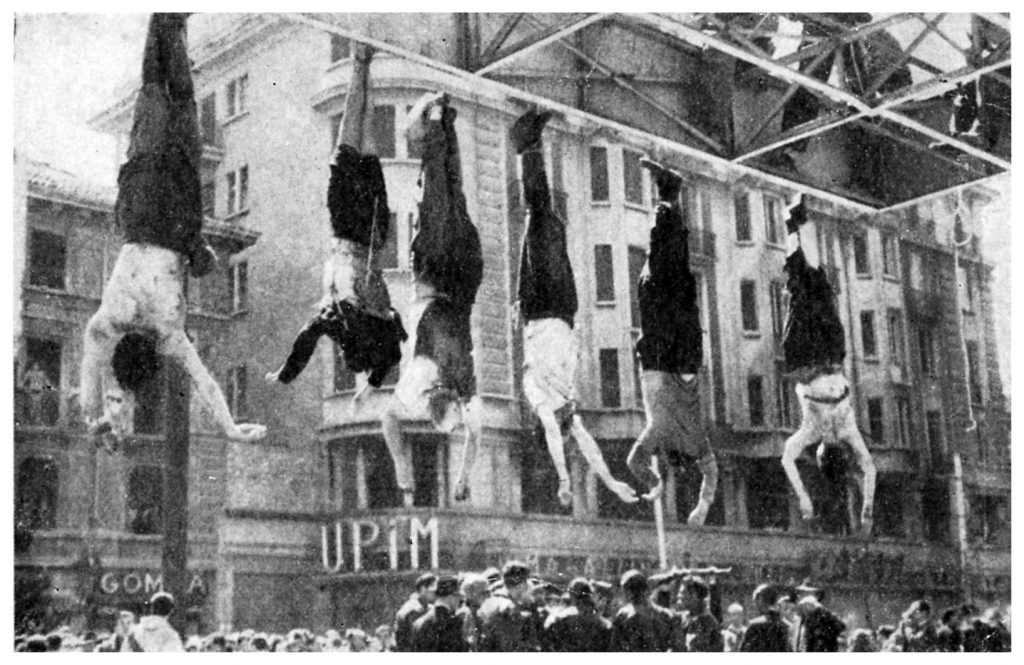

It led to Mussolini’s own deposition in 1943, a short but extremely bloody restoration to power under German aegis, and his violent death at the hands of partisans in April 1945. The leader who had earlier held millions in thrall left behind a country in ruins.

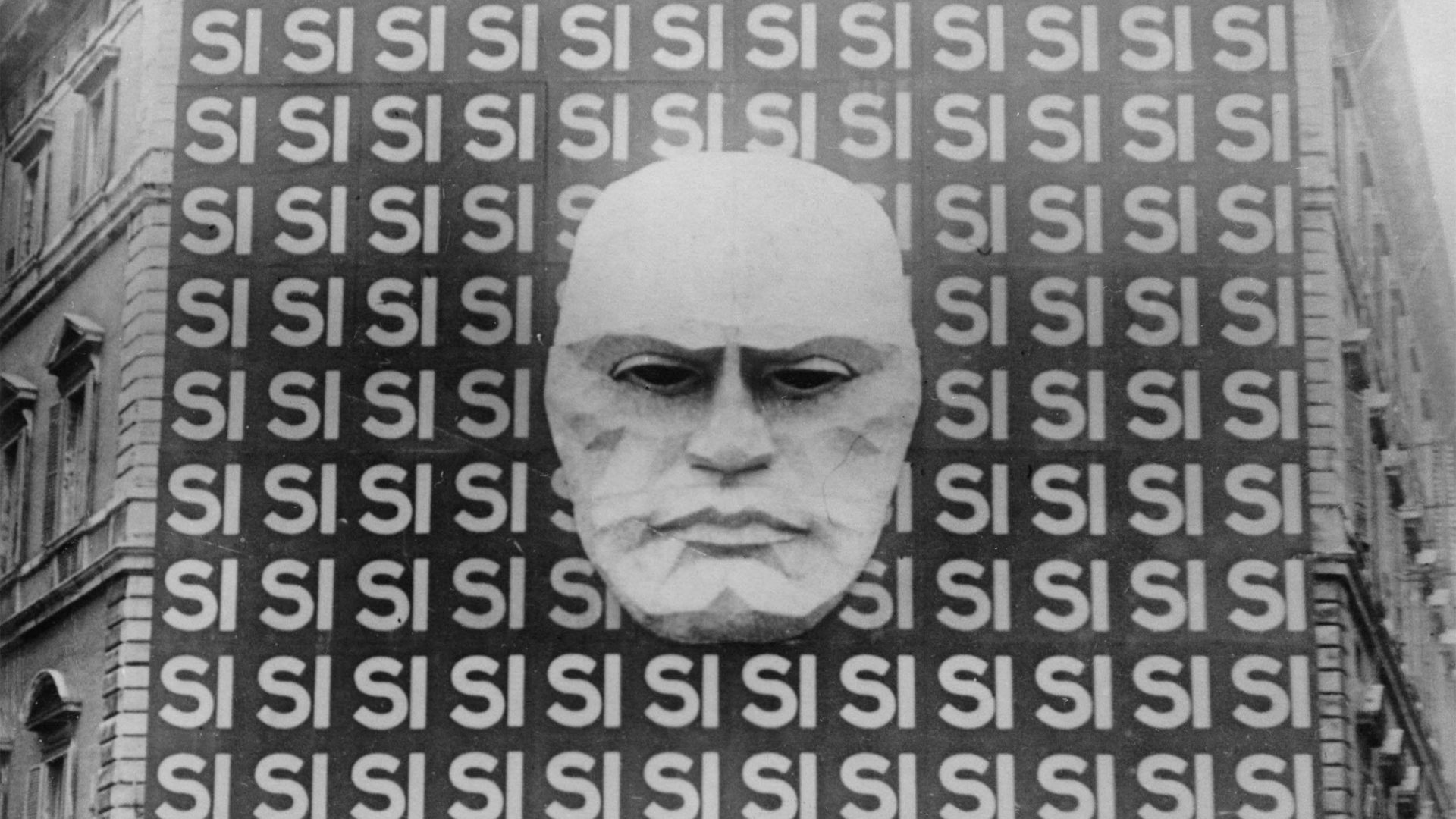

Short (only 5 feet 6 inches tall), squat, bald, with outlandishly histrionic gestures, exaggerated “manliness”, strutting arrogance, pugnacious face, rolling eyes, jaw aggressively jutting out, legs astride, chest puffed out, Mussolini was a caricaturist’s dream. His image as dictator easily fostered the assumption that, beneath the pompous bluster, he was little more than an absurd, clownish figure, “a vain, blundering boaster without ideas or aims”, at most a “gifted actor” and propagandist. But that would be seriously to underrate what a malign, cruel individual he was, the baseness of his character, the brutality of his politics and the assault on humanity that he directed as Italy’s leader.

His domineering personality had been visible at an early age. He was strongly opinionated, intolerant of opposing views, authoritarian in attitude, short-tempered, vindictive and an advocate of violence as a political method. He was unquestionably intelligent, with a quick mind and an excellent memory. He was intensely serious-minded, with little sense of humour. He admitted to having few genuine friends.

To a later age, few features of his character seem attractive. But to many of his contemporaries, alienated by decades of ineffective, corrupt factional government exercised by a seemingly unchanging dull oligarchy of liberal notables, Mussolini exuded vitality and energy.

His well cultivated manly, virile, martial demeanour fitted a widespread accepted ideal of strong leadership. He certainly never lacked female admirers. He seems himself to have been practically addicted to sex. His countless, mainly fleeting relationships stretched from his early years to his last – in this case strong – attachment to the woman who would share his fate in 1945, Clara Petacci. His wife, Rachele Guidi, who married him in 1915 and bore him five children, put up with what she could not alter in his character and behaviour.

He had come from a poor background. He was born in 1883, the eldest of three children, in the hamlet of Dovia in the Predappio district of Emilia-Romagna in northern Italy, a provincial backwater in no easy reach of the nearest cities of Bologna and Ravenna. His father, Alessandro, a blacksmith and smallholder, was an early enthusiast for socialism (tinged with anarchism), critical of the Church, landowners and the political establishment, and served for a while as a councillor in Predappio. Both his socialist leanings and his choleric temperament rubbed off on his son.

Benito’s mother, Rosa, was more gentle, the local schoolteacher and, unlike her husband, a pious Catholic. Benito was a bright boy who read a good deal, and had some talent for music. But his involvement in two minor stabbing incidents during his school years already showed a violent streak.

By 1902 he was beginning a career in journalism, writing for a socialist weekly and displaying an aptitude for provocation and agitation, which brought in subsequent years clashes with the police, arrest and short periods of imprisonment.

At the outbreak of war in 1914, Mussolini was still a committed socialist. But that was very soon to change. His socialism was, in fact, eclectic. He knew his Marx.

But he was ready to draw, where it suited him, on other ideas, including Vilfredo Pareto’s theory of elitism, Friedrich Nietzsche’s “will to power” and Georges Sorel’s “struggle against decadence”. Ideas in themselves were not important to him unless they could mobilise, unless they were vehicles to power.

He quickly became one of the foremost advocates of intervention (which took place with Italy’s entry into the war on the side of the Entente – Britain, France and Russia – on May 23 1915). Within a fortnight he had launched a new paper to support the cause, Il Popolo d’Italia, initially still left wing in tone, but financially backed by industrialists who stood to gain from Italy’s intervention in the war. By 1922 it was the official paper of the Fascist Party.

By December 1914 the editorship of Il Popolo d’Italia gave him the publicity he needed to become the chief spokesman of the small groups – some of whose members were ex-socialists who favoured intervention – calling themselves Fascists of Revolutionary Action, though their influence at the time was negligible. (Fasci was a term that loosely meant “groups”, after the bundles of rods that were the symbol of order in ancient Rome.)

In Mussolini’s thinking, national revolution had meanwhile replaced a Marxist understanding of class struggle. He saw a struggle not between classes, but between “proletarian” and “plutocratic” nations. Establishing Italy’s stature as a great power, not fighting for the triumph of the proletariat within Italy, was his new gospel.

By February 1919, small numbers of seriously disaffected but politically rootless individuals, mainly intensely aggrieved veterans, were starting to come together, calling themselves Fasci di Combattimento. On March 23 1919 Mussolini summoned a meeting of around 50 of them to form such a grouping in Milan. It was one of 37 similar groupings in Italy at the time. But this one, under Mussolini’s direction, would prove the basis of what became the Fascist Party.

From there to the “seizure of power” in 1922 was a long and winding path. Little of this route was under Mussolini’s personal control. There was nothing inevitable about Mussolini’s takeover of power. Without the prevailing social, economic and political preconditions his dictatorship would not have been possible. Without the intensely damaging, deeply polarising effects of the first world war on Italy, without the widely perceived threat of socialist revolution that prompted a breakdown of order, and – even then – without the readiness of the conservative powerelites to make him prime minister, Mussolini would never have become Italy’s dictator.

The war left behind a demoralised population, angry at the country’s leaders, humiliated by military weakness. The ruling class of liberal notables had forfeited any claim to popular legitimacy. They felt forced to widen the extremely restricted electorate, granting the vote to all adult males in December 1918. The voting system was altered to introduce proportional representation the following year. This resulted, however, in big gains in elections in November 1919 for the socialists, now easily the largest party in parliament and declaring that they wanted to destroy the bourgeoisie. The other big electoral winner was the newly founded Italian People’s Party (the Popolari, representing Catholic interests). The upshot was that the liberal-conservative elite was no longer able to control and manipulate parliamentary politics. As disorder mounted, the unstable governmental system could not cope.

The social order, and the power that went with it, seemed under threat. The prospect of socialist revolution – a fearful spectre in many people’s eyes – loomed large. The social, political and ideological turmoil spawned by the war intensely sharpened class conflict. Strikes, factory occupations, looting of shops and seizure of land in 1919 and 1920 – the biennio rosso (two Red years) – seemed to denote a political system out of control. The middle classes, seeing their savings eroded through inflation and their property threatened, wanted order. Reports, embroidered by the right wing press, of Bolshevik terror in Russia left them terrified about the threat of socialist revolution in Italy. The foundation in January 1921 of a Communist Party looking to Lenin’s Russia did nothing to soothe the nerves.

This is where the various small paramilitary organisations calling themselves Fasci came in useful. Demobilised ex-servicemen formed the initial core of the fascist movements that now sprang up in towns and cities of northern and central Italy. As the movement expanded, it recruited across the social spectrum, though not strongly among the urban proletariat, and its leaders were predominantly middle class. Students (mainly from middle-class backgrounds) were significantly over-represented among the members of the paramilitary squads. Most obviously early fascism was an overwhelmingly male, youthful movement. There was no coherent ideology. But there was intense rage at the corrupt liberal establishment and demand for violent action to destroy what they saw as a rotten state whose leadership had betrayed the nation. This is what fascism boiled down to: complete destruction of the old political and social order and utopian promises of a new society driven by belief in national rebirth and glory.

The numerous fascist groupings, not just Mussolini’s, quickly became a vehicle to repress socialism and destroy any stirrings of social disorder instigated by the left. Though initially an urban phenomenon, by 1920 fascism was spreading rapidly into the countryside of northern Italy.

Landowners recognised the value of financing paramilitary bands of fascist thugs (squadristi) to evict troublesome tenants, break strikes, beat up opponents and terrorise socialists or anyone else who stood in their way. Landlords started only to hire workers who were members of fascist organisations, which were incorporating earlier anti-socialist “citizen defence” militias. By 1921 the fascists were being aided by government money and arms; the police stood by as they inflicted horrific beatings on hapless opponents.

Without the support of the fascists, the members of the cabinet reasoned, there was no hope of bringing stability to the country’s governance. They were far more worried by the socialist left than the fascist right, and when Mussolini’s forces crushed a feeble socialist-inspired attempt at a general strike in August 1922, they could perversely interpret fascism as the defender of the law – even though they knew he was preparing an armed insurrection. The conservatives felt they could not rule without the fascists. But without government support, the fascists were not strong enough to take power. The basis of the political deal that would give power to Mussolini took shape. Government ministers believed they would be able to control him. It was the mistake that, little over a decade later, the German political elite was to make about Hitler.

Mussolini played a double game. His political duplicity was a big part of his success. He encouraged, on the one hand, the violence of the fascist squads and fired up his militants to seize power by force. On the other hand, he portrayed himself to leading members of the government as the only man who could restore order in the state and rebuild the economy.

The prime minister, Luigi Facta, a liberal in office only since February 1922, dithered until the night of October 27–28. The violence of fascist squads (in which 22 people died) had by then escalated menacingly. Facta finally bowed to the request of Rome’s army commander to impose martial law and declare a state of emergency. The army had shown that, when it wanted to, it was well able to suppress fascist mobs; overnight the occupied buildings were retaken with ease. Crucially, King Victor Emmanuel III agreed to sign the declaration of the state of emergency. Then he changed his mind. He was wrongly informed that the army would be unable to defend Rome against the fascist militia. In fact, it would have had no difficulty in crushing the weakly armed fascist militia, numbering no more than about 30,000, poised outside Rome.

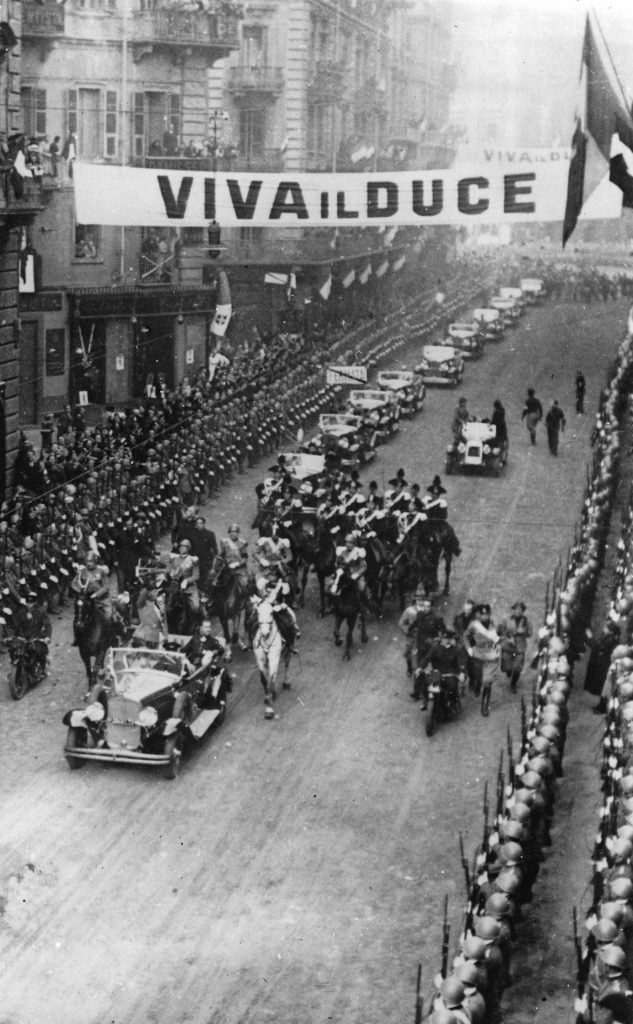

Myth, in a dictatorship, is often more powerful than fact. The image of the heroic leader on horseback at the head of his legions in a triumphant “march on Rome” became the foundation legend of Mussolini’s rule and a staple of the Duce cult. In reality, after agreeing his appointment as head of government with the King, and that tens of thousands of squadristi would march past and salute the sovereign before returning home, Mussolini travelled to Rome by train from Milan, wearing a suit and a bowler hat. He had not “seized” power; he had been invited to take it. On October 29, 1922, the King appointed Benito Mussolini as Italy’s prime minister.

Mussolini’s legacy was a country in ruins. He had plunged his country into a war that brought national catastrophe to Italy and inflicted death and destruction on parts of Africa and the Balkans. The entire Italian political establishment, despite misgivings at times, had backed him for over 20 years. A large, if unquantifiable, number of Italians beyond committed members of the Fascist Party had supported him at the height of his powers. Mussolini had hardly been the sole cause of Italy’s catastrophe. He had, however, been its central driving force. He plainly held chief responsibility. Without him the course of Italian history would have been less calamitous – certainly different.

Part of that history, which had helped to make Mussolini possible, had been Italy’s great-power pretensions. He had benefited from such aspirations, had magnified them through imperialist conquest, but had ended by obliterating them once and for all.

Italy’s future after the war lay in the negation of practically all that Mussolini had stood for. Postwar reconstruction, largely under American aegis, abolished the monarchy, established a democracy, the rule of law, a pluralist party system and a market economy (if one still with extensive state involvement) that opened Italy up to foreign trade. Where Mussolini had sought conquest and domination, postwar Italy turned to international cooperation and in 1951 was a founding member of the supranational entity that became the European Economic Community (and much later the European Union).

Mussolini’s political legacy was directly sustained by a neo-fascist party, founded in 1946, the Movimento Sociale Italiano. In elections it seldom won more than around 6% of the vote, but it fed into wider currents in Italian politics. Factional infighting and political adjustments have brought changes of name in recent decades and some distancing from Mussolini. Residual support for neo-fascism has remained at broadly similar levels.

A small hard core of unreconstructed fascist sympathisers have continued their devotion to Mussolini. Each year thousands of them still make the pilgrimage to his birthplace in Predappio.

After his death, fervent neo-fascists discovered and exhumed his remains from the initial unmarked grave in a Milan cemetery. After being kept in utmost secrecy for 11 years in a Capuchin friary near Milan, they were eventually reinterred in 1957 in the family crypt in his home town. On what would have been his 100th birthday in 1983, more than 30,000 neo-fascists turned up to pay homage.

Extracted from Personality and Power by Ian Kershaw, published by Allen Lane at £30. Copyright © Ian Kershaw 2022