There is a lot we think we know. But there is a lot more we truly don’t know. And the gulf between these two things is enormous. Donald Rumsfeld was once famously mocked for saying, “There are the known unknowns, and there are the unknown unknowns.” Another way of saying this is: the more you know, the more you know you don’t know. But it takes a wise person to realise the universal truth in this.

Over the last few years, I’ve started to wonder if my role in life is to ask the “foolish” questions loudly and fearlessly enough that we might clarify assumptions for the benefit of everyone. To simplify things enough for anyone to access and agree upon. To get to the centre of the spokes of the wheels of our interconnected lives, as it were.

My dad once explained to me that looking at why someone does something is more revealing than looking at what they actually did. Motivation gives a truer sense of understanding than action – the stories we tell ourselves are probably more important and powerful than we give them credit for. What then are the stories that govern society at large, in an age where everything seems to be falling apart, and somehow regressing?

Until several years ago, my creativity had two distinct strands: visual stories mostly enjoyed by children, and observational art mostly enjoyed by adults. These different creative veins began to come together with the arrival of my son, Harland, in 2015, when what started as a letter to him about being a human in the 21st century became the book Here We Are. All around me, the world suddenly seemed angrier and more bleak than before. It was hard to tell whether it happened quite suddenly or whether I was just noticing from the perspective of a first-time parent.

It occurred to me that my newborn son, like all fresh arrivals, knew nothing of the ways in which humanity governs itself and thus would need to be taught how to function in society. Over time, he would no doubt figure out his tastes and – despite the best efforts of his mother and me – would be exposed to prejudices, some of which he would take as his own. In other words: we all arrive here on Earth as unwritten stories.

At the time of his birth, the world around me really did seem to be unravelling. Stories of the growing transparency of inequality, a rising number of global refugees, divisive politics, the consequences of overconsumption, the fear of being replaced by a robot, the disposability of capitalism, and the cause and impact of climate-related natural disasters. But rather than just pointing out what was wrong and adding to the ever-growing noise of anger reverberating around the planet, I tried to remain hopeful, and search for a deeper pattern.

In forcing myself to consider how I feel about these issues, I started to find that my – at first forced – optimism had genuine roots. I realised that our collective future may likely not be headed toward the dysfunctional dystopia we fear and frequently hear about. Perhaps it’s less that the world seems to be unravelling, and more that we are now suddenly, and really for the first time ever, aware of everything happening everywhere, simultaneously and instantaneously. We are now in a time when we have medicine for almost all ills; when we can expect to travel anywhere on this ball and to return, all before a season changes; when humans can talk to other humans anywhere, at any time, with immediate access to all information (real and fake).

This optimistic and privileged view is not to say that everything is going perfectly. Far from it. We are a ways away from resources being fairly distributed and society being equitable. Injustices abound, and all of them need to be addressed. There is still war, famine, and poverty, and not everyone has this same access to travel, education, or medication that is so deeply needed.

And while there is much to be worried about, and it is easy to feel that civilisation is headed in the wrong direction, the idea that we are all doomed and the planet is broken doesn’t sit well with me. It feels fatalistic to resign ourselves to that idea. We will do what we have always done – we will adapt. We just need to do so faster. And together.

I grew up in the politically divided and violent city of Belfast, Northern Ireland: a place where two opposing communities became insular and defensive to the point that their own identities became dependent on the existence of an enemy. I know all too well the destructive patterns of thought that foster an “us” versus “them” mentality – “I don’t know who I am, but I know who I’m not”. Cultures have clashed for millennia – history suggests that’s what we tend to do when we encounter a new group: define our collective identity by our common enemy.

I was raised as a Northern Irish Catholic and have experienced much of the grace and advantage that comes from being born into the body I inhabit. I have benefited from the stories written by, and for, people mostly like me. But I have also experienced what it is to come from a (indeed the original) British colony. For most of the 20th century, Northern Irish Catholics were treated as second-class citizens. But by the mid-1980s, when I was a child being shielded on one hand and educated on the other, the origin of all this conflict was lost on me. It had always seemed obvious that it was never a religious war. Partly because I’d been told a particular set of stories, partly because I’d been made to compare these stories with others, and partly because I hadn’t been told an array of other stories at all.

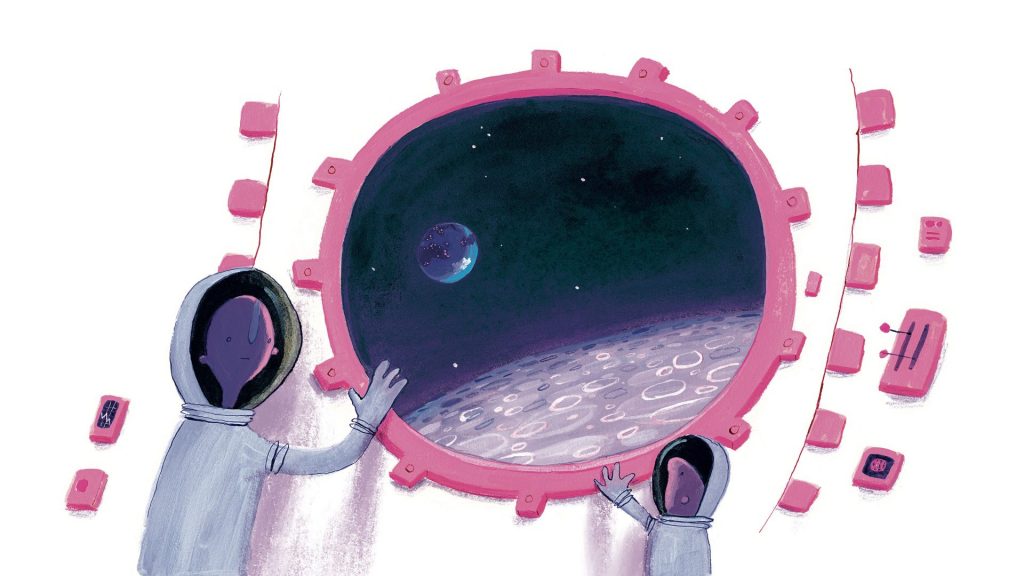

In 2007 I moved to New York City, where having a Belfast accent seemed to be an asset rather than the hindrance it was in London back then. At first I was shocked and hurt that no one on the other side of the Atlantic seemed to really know or care about the politically divided and traumatically violent history of where I came from, I came to accept that – we are an unimportant, inconsequential part of the top left-hand corner of Europe. We were all alone, killing each other in a fight to be part of either a larger Irish or British identity, but once beyond our borders, no one seemed to care. I wasn’t sure what to do with that disheartening reality. Until I started reading about astronauts.

There is a phenomenon known as the overview effect, where any human who has been far enough from the surface of Earth tends to have the same shift in their perception of humanity when they see our collective story from the distance of outer space. I immediately recognised the way they described looking at Earth from space was how I’d been talking about Northern Ireland from across the distance of the Atlantic Ocean. With distance comes perspective.

The summer after my son was born, there was international concern with the growing violence back in Belfast. It was kids who were rioting with each other and with the police. I wondered what these teenagers truly knew of the nuance of an 800-year-old conflict. They’d been told who to hate and so they hated. This, I told myself, was not the story I was going to tell my children about where they came from. The most powerful thing we can do as civilised human beings is change the story. We can always, always change the story. We can choose to make a pattern of sense out of events to be governed by things other than fear or hate, anger or indifference. We can change our own story.

People are all, simply, a collection of stories: those we are told, those we tell, and those told about us. People become the stories they believe.

I left Northern Ireland thinking that no one will ever understand these weird internal conflicts of ours. But – having been in New York City for the brutal 2016 US election cycle, and then watching the even more brutal 2020 election cycle from across the ocean – it seemed that in America, revenge politics was coming to dominate personal thinking. If “they” think it’s right, it must be wrong, whoever “they” may be. In Belfast, I was able to consider where several generations of divisive thinking gets you. Not far, if anywhere.

I noticed that I’d started taking much of my feelings on geopolitics from watching my wife be a mother. I learned that you’ll never get someone to change their mind by telling them they are wrong. Your stance may seem true and obvious to you, but emotionally, this aggressive mode of communication doesn’t work, it merely manifests a defensive mentality.

On returning to Belfast, I saw a paramilitary mural depicting two masked gunmen accompanying the slogan “we deserve the fundamental right, if attacked, to defend ourselves”. This was a global problem, not just a local one. When I ask people, “What kind of a world do you want?”, they tend to answer with what they don’t want rather than trying to imagine their ideal future world and how to achieve it. They are answering a positive question with aggressive defence. Is it simply easier to blame something with a face than to blame an abstract concept like when your reality turns out to be different from the story you were promised?

I have travelled all over the world on book tours. I have met many people from all backgrounds, belief systems, and political leanings. I very much believe the vast majority of people on Earth are good people. We are built to help each other and work together. I’ve never met anyone who actually wanted to be disliked, even among the people who’d often be considered assholes. They, too, just wanted a better life for themselves. For their children.

But what is a better life?

These days, instead of asking people what they want, I ask, “How do you want to feel?” To feel safe, to feel that we belong, to feel we matter. And growing numbers of people despair that they don’t. That they have instead been forgotten, left out of the collective story of modern society.

In a chance encounter with an old lady waiting to cross the road in Belfast during the pandemic, I asked if she thought we were in for a long road. “Yes,” she responded. “I was around during the [second world] war, and back then everyone tried to see how they could help, but look around, everyone today just tries to see what they can get away with. We aren’t getting out of this quickly because no one is going to cooperate.” When did this fissure begin? How did we go from community to individual?

Around the world, there is a growing trend toward populism. The stories that bind these groups tend to be hateful ones, offering something or someone to blame rather than a sense of purpose. But it works because these new stories include the people they are being told to. They are giving people who feel forgotten a sense of purpose, however shallow.

I’ve always believed the most powerful human emotion is not hate, not fear, not even love, but hope. Hope separates us from other animals, as it requires imagination about an unwritten future. The ink on the next few hastily written lines of that untold story of the world we might live in is barely dry, and we are already wary of its premise.

The antiquated stories of old have little place in the world we are working toward. What future collective story would we rather compose? Certainly one that further builds on and encourages those already written, strong in their foundations of hope and inclusion. Creating these new stories, these new systems that work for everybody, is an enormous undertaking. It will require the largest army of people ever assembled at a time when an enormous number of people feel lost, without cause or purpose. How, though, do we begin?

A simple place to begin shifting these disjointed motivations might be to make a conscious effort to replace “right” and “wrong” with “better” and “worse”. It’s not hard to see how a simple shift in perception can change everything. Imagine a scenario where we all become energised by a much better story – one that aims toward a flourishing future, instead of being driven by being “right” or by what we can just get away with. Aside from safeguarding the future of civilisation, it might make the brief time we have being alive on Earth all the more beautiful and joyful too.

When the Apollo 8 astronauts turned and looked at Earth as they rounded the moon, they couldn’t work out what part they were looking at. It took them longer than expected to realise it was the horn of Africa. Because it was sideways. We’ve been conditioned to think of the map with north at the top, but there is no up or down to our planet. This is just a system we created for ourselves. A story.

To put this perspective shift into practice, scientifically we are at the outer edge of a small galaxy, far from the brightest points. Instead of saying we are in a cold and lonely part of space, we could find comfort in this: if this is the only place life exists, we are in the least lonely place in the universe – the social heart of the cosmos.

I hope for a new beginning where we question how we think about our role in an unknown future – a future that has yet to be written. A story we must all tell, together.

Oliver Jeffers is a bestselling author and illustrator. His new book, Begin Again, is published by Penguin Random House and HarperCollins