I aspired as a teenager to a certain degree of chicness that at the time I thought could only really be manifested through cultivating a hobby of analogue photography.

For an A-level art project I wandered self-consciously through central London taking photos of corners of my home city, which I then precociously developed in the school dark room – shots of the grey waves of the Thames lapping at the steps of Waterloo pier; dramatically cropped traffic lights, and other cliched vistas of the urban landscape at street level. Much to my disappointment, my art teacher found them arbitrary and banal.

I was memorably wounded, convinced of the intangible poetry of the everyday environment that I had tried, in vain, to capture.

At the time I, (and most probably my art teacher), hadn’t yet read the work of French author Annie Ernaux, whose chronicles of everyday life in all its quotidian mundanity have formed the basis for a thought-provoking exhibition at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie (MEP) in Paris.

Exteriors: Annie Ernaux and Photography brings together 150 works of international street photography from the MEP collection to sit alongside printed excerpts from Ernaux’s 1993 book, Journal de dehors (translated as Exteriors in 2021).

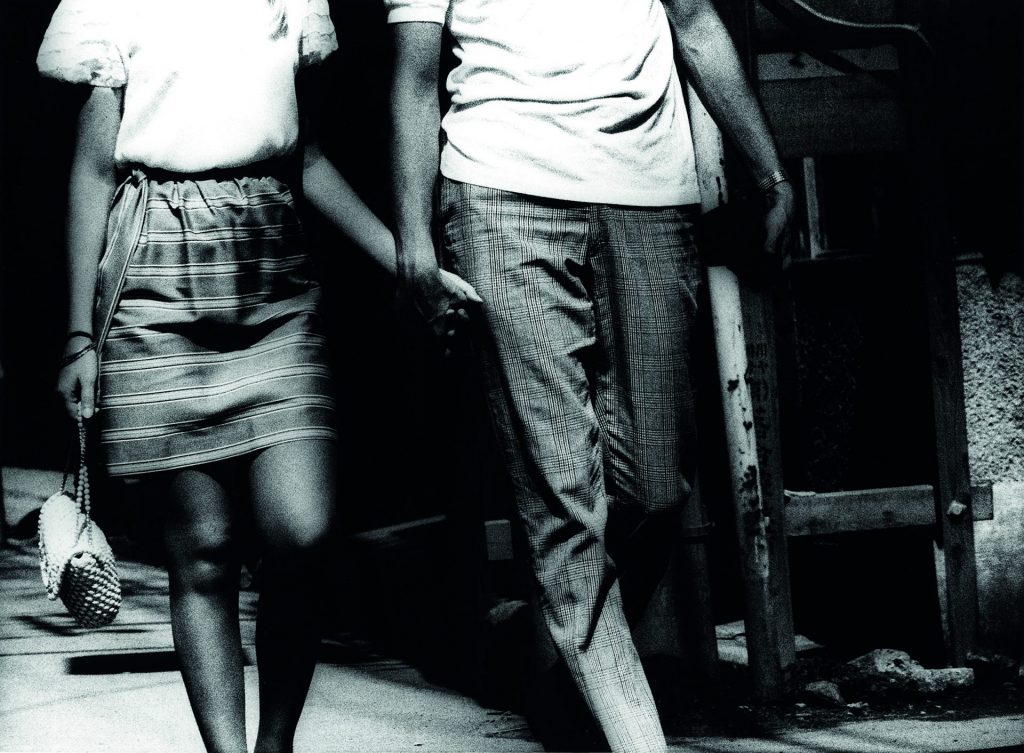

The slim volume compiles observed vignettes from everyday life in the French town of Cergy-Pontoise written by Ernaux between 1985 and 1992. Here we find descriptions of locals queuing at the butchers, passengers on the RER commuter train; the view from the supermarket car park. Mostly these are glimpsed fragments of exchanges and actions in places of commerce or passage; ephemeral, unmemorable moments of day-to-day life that in Ernaux’s hands yield social and psychological insight and narrative.

Ernaux is a writer for whom the “supermarket can provide just as much meaning and human truth as a concert hall”, and for whom “desire, frustration and social and cultural inequality” are reflected in the contents of a shopping trolley.

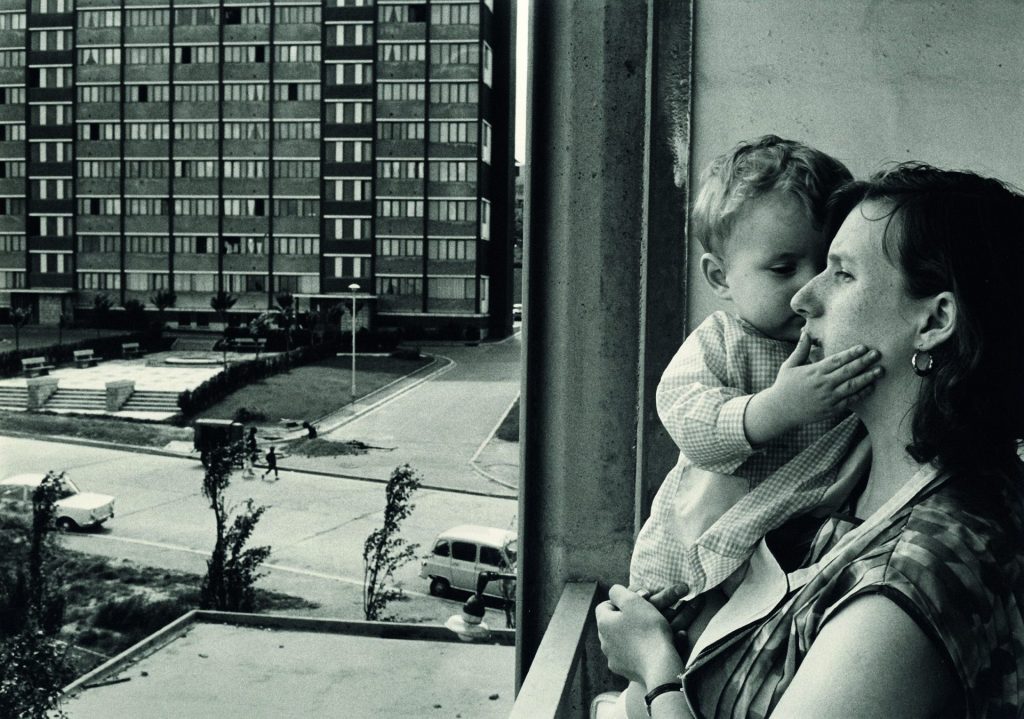

In some ways then, Exteriors is something of a micro-history of the postwar town of Cergy-Pontoise, which sits 30km outside Paris, one of four “new towns” that emerged from the SDAURP (Schéma directeur d’Aménagement et d’Urbanisme de la Région Parisienne) plan of 1965, and which has been home to the writer since 1975.

Ernaux describes it as “a place sprung from nowhere, a place bereft of memories, a no man’s land half-way between the earth and the sky”.

This melancholy ode to banality may seem an unusual place for a Nobel Prize winner to remain (Ernaux won the Nobel Prize for literature in 2022, the first French woman to receive the accolade). But Cergy-Pontoise has been proverbial grist for her mill, the raw material not only for Exteriors but also for two other books; La Vie extérieure (Things Seen) and her diary of visits to the hypermarket, Regarde les lumières mon amour (Look at the Lights My Love). Her gaze on Cergy is both sympathetic and judgemental, delivered via piercingly crisp analyses: the mother and daughter with matching tracksuits and espadrilles loudly eating crisps and talking about magazines on the way back from the coast; or the man with “huge thick glasses and small grey hands” who invites shoppers to purchase wares in the Trois-Fontaines shopping centre.

Throughout the exhibition our eye is invited to scan between snippets of text from Exteriors and the photographs on the wall, sometimes finding a chord of resonance between the two, sometimes an explicit if coincidental symmetry. But the intention of the show is in some ways to sit in the space between the two, to ask whether the photograph can be “read” in the same way as a text, or if words can freeze-frame the flow of reality as if it were a photograph.

The exhibition opens with a passage from Exteriors in which the author explicitly states her ambition to “describe reality as through the eyes of a photographer”. For London-based curator and writer Lou Stoppard, this text provided the initial impetus for the exhibition, followed by a month-long research residency at the MEP.

While Stoppard may have chosen Exteriors as her linchpin for the exhibition, the way in which memory and every day experience are conjured up as images is a recurrent theme running through much of Ernaux’s writing. In her masterwork Les Années (The Years) from 2008, photographs of the author’s past serve as aides-mémoire in a richly textured flow of snapshots of personal and collective memory; from bygone adverts, to television bulletins.

While she is committed to transcribing life as it unfolds in real time, Ernaux remains always aware of the photograph’s moribund associations: “all the images will disappear”, she writes in the opening of The Years. These links are less explored in the MEP show, although all photography brings us closer to our own eventual obsolescence.

As Susan Sontag wrote: “Photographers, connoisseurs of beauty, are also – wittingly or unwittingly – the recording-angels of death… We no longer study the art of dying, a regular discipline and hygiene in older cultures; but all eyes, at rest, contain that knowledge.”

Acutely aware of her own personal mortal coil, Ernaux co-wrote L’Usage de la photo (Uses of Photography) in 2005 with her then lover, Marc Marie, while she was undergoing cancer treatment. Over the course of 14 mornings the couple repeatedly photographed their discarded clothes and the mise-en-scène of love-making from the night before as a way of observing their relationship in the face of illness. (The English translation by Alison L Strayer is forthcoming in October this year).

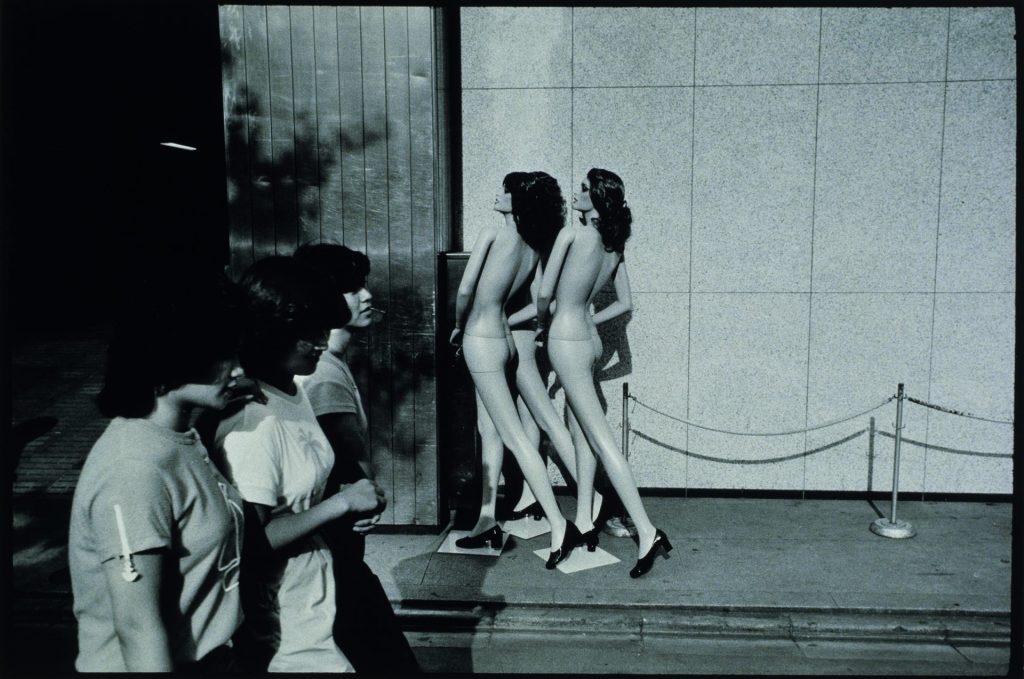

Ernaux’s subject matter of daily life as a source of philosophy and poetry is richly steeped in French cultural tradition; in his 1893 book The Painter of Modern Life, Charles Baudelaire defined the figure of the flâneur, the city walker who stalked the urban landscape of 19th-century Paris, observing all the theatre, decay and ennui of modern life with an omniscient, detached gaze.

But while Baudelaire’s flâneur was emphatically male and monied, Ernaux’s gaze is that of a woman, who is also a mother and a writer from humble origins who is fully embedded into the community she records.

The exhibition poster for the show is plastered all over Paris. It takes a photograph from the exhibition – Dolorès Marat’s Woman with Gloves – an anonymous figure with coiffed hair who is seen in profile, descending an escalator against a mosaic of azure tiles. It’s hard not to see this as the disguised figure of Ernaux herself, weaving through the urban everyday spaces as an invisible chronicler who in turn plays a part in the observations of others, entering into their thoughts at a semi conscious level.

She writes: “I myself, anonymous among the bustling crowds on streets and in department stores, must secretly play a role in the lives of others.”

It is this sense of interconnectedness in the modern city that also recalls French philosopher Michel de Certeau’s book L’invention du quotidien (The Practice of Everyday Life) first published in French in 1974. For de Certeau, the city is an intersecting mass of living, walking stories shaped by those who pass through it, even in the face of the estranging forces of consumer capitalism and the regimentation of our free time.

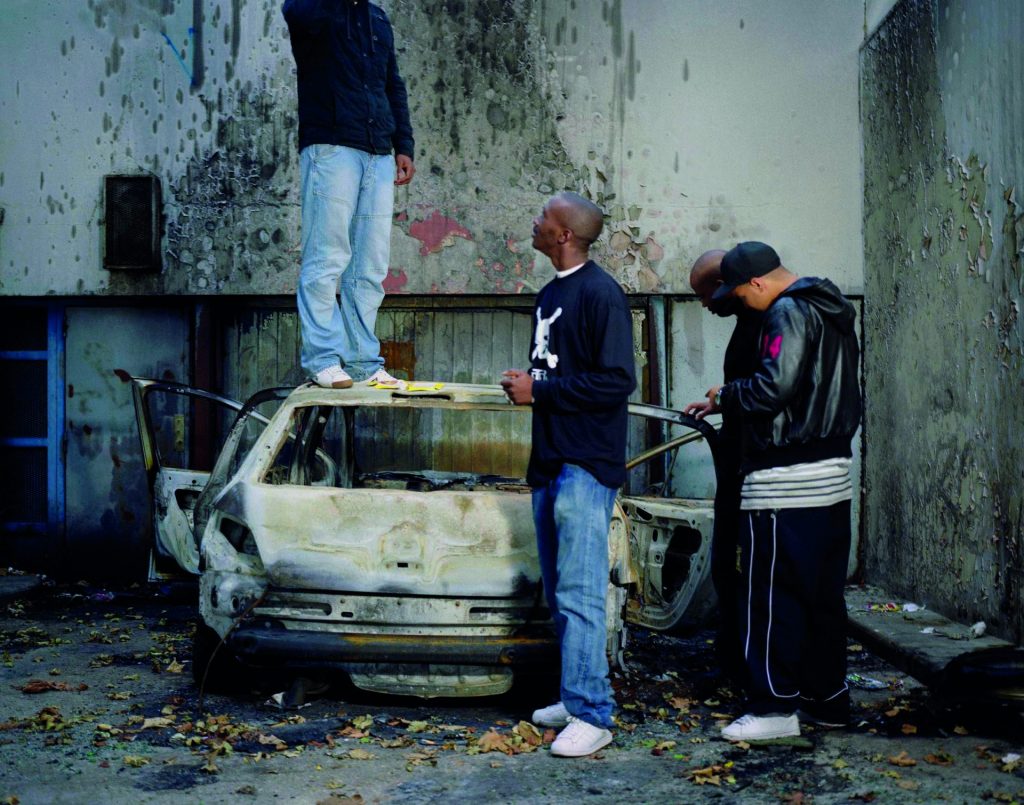

But not everyone has access to the same spaces of the everyday, as the photographs in this show acutely reveal. Marat’s image of the middle- class matron about town contrasts with a photo in the final room of the exhibition – a mother and child on a Vitry council housing estate looking out from their concrete eyrie in the middle of a tired afternoon.

Elsewhere, Bernard Pierre Wolf’s photographs of New York and London in the 1980s take us to the spaces of the most lonely and marginalised. But there is no heroising here. Ernaux’s observations do not glamorise the proletariat from the condescending safety of the intellectual left, nor does she romanticise the plight of those who are alienated by the modern city.

On the sunny afternoon of my visit, the luminous rooms of the MEP were thronged with visitors. Overall, it feels as if they are here less for the photography than for thinking about Ernaux, who has enjoyed widespread acclaim in France in her lifetime, even if it is only relatively recently that she has generated a hungry audience of international readers outside her native country, accelerated by her recent Nobel success.

I left with the resounding feeling that the banal and quotidian is perhaps the greatest source of poetic reflection on the human condition.

But there’s also something timely about Ernaux’s observations that feel like relics of an era before our mass hypnosis by smartphones, of a recent past when transit on buses and trains was an empty space for day-dreaming, observing, and pondering the exterior lives of each other, and in doing so, connecting more with the banality and poetry of our own interior lives.