Heard any good books lately? If audiobook sales are any indication it’s likelier than ever that you have.

Last year we bought an unprecedented £151million worth of audiobooks, up from £133million the year before and considerably more than the £5million sold just a decade ago.

The hot take on these figures is that the pandemic is responsible for the boom but a dramatic upward surge was in place long before the spring of 2020. If anything, lockdowns were more likely to have slowed the surge in sales – while many people found themselves with more time on their hands, nobody was commuting or travelling long distances, which is when most people listen to audiobooks.

These soaring figures echo a general growth in the wider world of audio. Nine out of ten of us listen to the radio every week and that’s before even thinking about podcasts, of which there are a startling amount (I’ve heard a rumour that there is one person somewhere in the country who doesn’t have their own podcast, but it’s unconfirmed – and they may well have started one by the time you read this).

Audiobooks were once very much the poor relation of their physical and e-book counterparts. Before streaming they were expensive, unwieldy and impractical – an unabridged version of a standard-length book filled anything up to a dozen CDs housed in horrible moulded plastic packaging the size of an encyclopaedia.

Abridged versions were given slightly sexier treatment but were still only a selection of the book’s contents – and why would you want a book with loads of pages missing? Add to this a lingering perception that audiobooks were made specifically for the blind, and the format seemed destined to remain a quiet cul-de-sac off the literary highway.

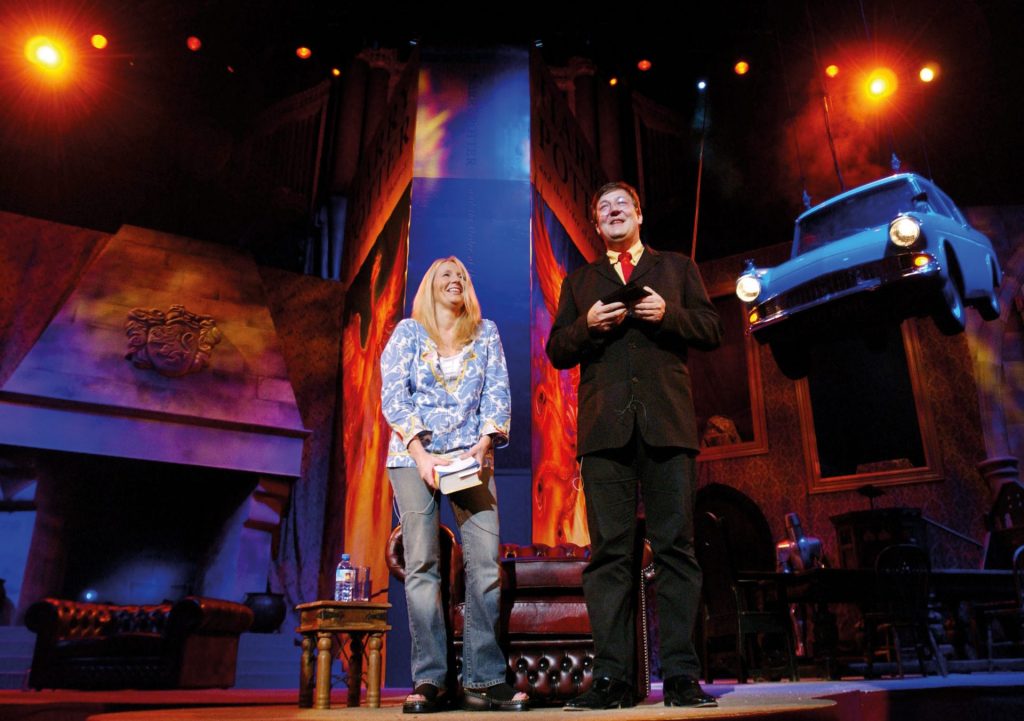

Then streaming came along and changed everything. Now you could carry the entire career of Ian Rankin’s Inspector Rebus around on your phone and have Stephen Fry permanently on standby to read Harry Potter to you while you were assembling an Ikea bookcase or stuck between stations on the 07:54 to Manchester Piccadilly. No more flipping through a pile of CDs bigger than the entire Beatles oeuvre to find that chapter of The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time where you left off last time, instead you could now take the complete works of Charles Dickens on your couch-to-5k slog around the park.

The arrival of subscription services and online loan portals developed by public libraries meant you didn’t even have to go through a tedious checkout process any more, you just made your selection and hit ‘play’. The audiobook was no longer a plastic tub of CDs on which Martin Jarvis read Maeve Binchy for your nan because she couldn’t read it herself with her cataracts – suddenly audiobooks were cool.

OK, maybe not actually cool, but certainly a viable, convenient and popular alternative to their print counterparts.

So fast has demand for audiobooks grown that the supply of titles is struggling to keep up. Today, new audiobooks are given the full treatment by publishers and production values for the highest-profile titles can be spectacular – the audio version of George Saunders’ 2017 Booker prize-winning novel Lincoln in the Bardo effectively became a play, with characters voiced by Hollywood actors like Ben Stiller, Susan Sarandon, Julianne Moore and Nick Offermann.

The flipside is how thousands of books that predate the listening boom have no audio versions available and catching up presents the industry with a significant problem.

Audiobooks are time-consuming to produce. You have to select the right reader, then you’re looking at a week in the studio to record a full-length book, plus time for editing and polishing. Studio hire and readers’ fees make it an expensive business too.

Faced with all that and a backlist of thousands of titles at major publishing houses, how would you begin to choose which books to record first?

This month has brought a possible solution, with Google Play inviting publishers in the UK, the US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Spain to create, publish and sell ‘auto-narrated’ audiobooks on their platform. That is, your favourite books read by a disembodied, computer-generated voice.

We’ve come a long way since every computer-generated voice sounded like Metal Mickey, and the Google Play system offers publishers a choice of 35 different narrator options featuring varying accents, ages and genders. All they have to do is choose one, upload the text of the book and, bingo, there’s your audiobook. Minimal cost, minimal time spent, everybody wins, right?

I like to think I know a bit about audiobooks. Way back in 2008 one of mine, read by Alex Jennings, no less, came second in a Guardian/ Waterstones public vote to find the greatest audiobook of all time. Of. All. Time. Granted, the list of candidates back then was probably in the dozens rather than thousands, making it a bit like being voted the second-best pole-vaulter in the old people’s home, but there I was, second, behind only The Hitch-Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.

Since then I’ve even narrated audiobooks myself, so it was with a rare feeling of authority that on learning of the Google Play initiative I immersed myself in the world of literary auto-narration.

Of the English language options among the readers offered, 12 are American, three Australian, four British and five Indian, with samples available of all of them reading the opening lines of The Wizard of Oz.

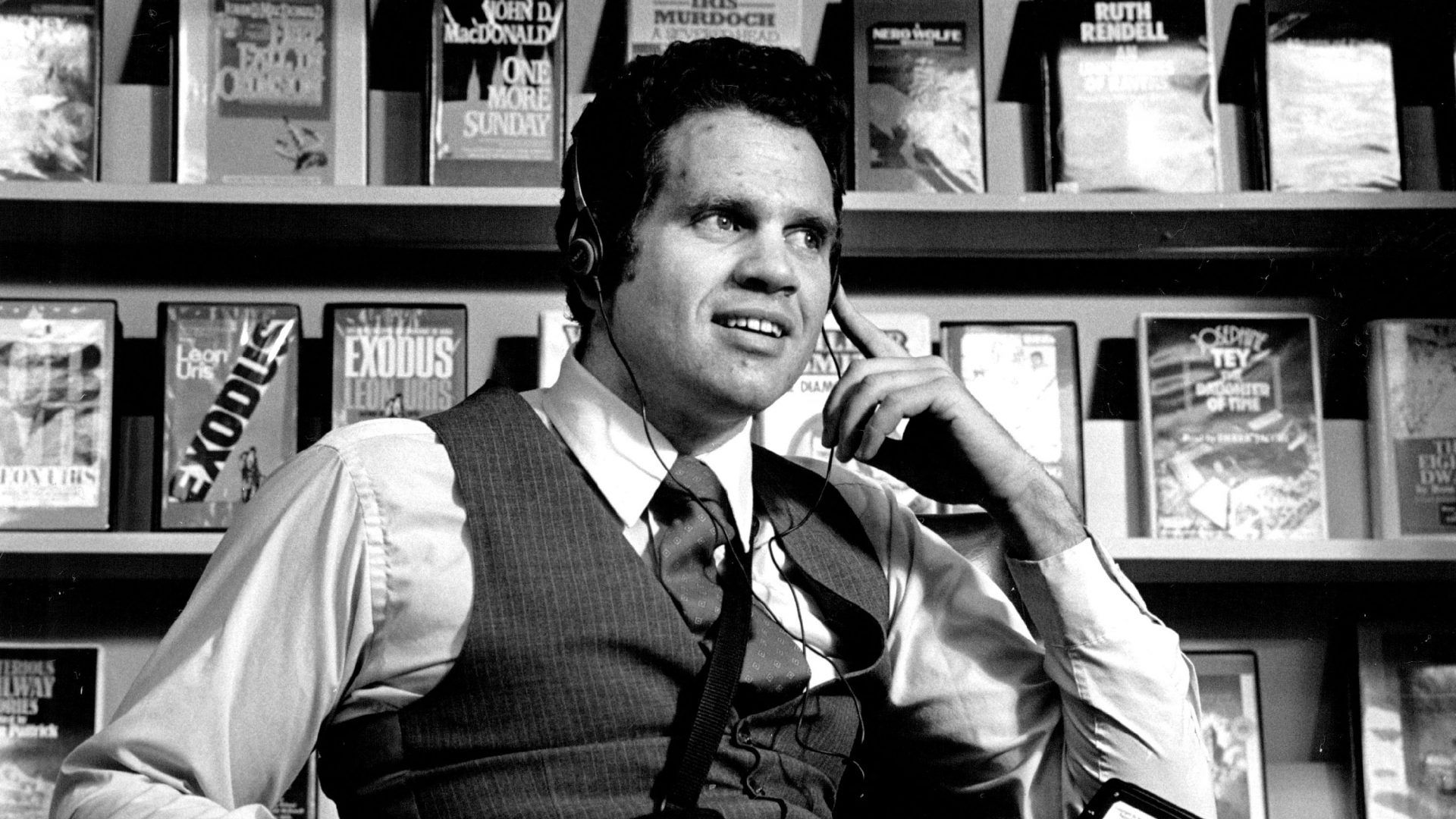

I tried them all. 24 of them, one after the other, each reading the same few sentences. The succession of disembodied voices coming through my headphones did give me an idea of what life might be like as a spiritualist medium but also confirmed my hunch that auto-narrated audiobooks will never even come anywhere close to matching those read by actual people.

The voices were impressive in many respects, the accents, the diction, even the individuality; there were faint traces of a constructed personality in each. If they were telling you in which direction your lift was about to go and what floor you were on, you’d be happy. Unfortunately, anything longer than that just sounded bewildering, making the most important part of the whole process, the delivery of the text, a disaster.

Each voice put the stresses in the wrong places and there was a complete absence of rhythm and timing. The random stresses and idiosyncratic variations in tone and pitch made even a sentence as simple as “The house was small, and the lumber to build it had to be carried by wagon many miles” sound so bizarre that those garbled terms and conditions you hear at the end of radio ads seemed like Richard Burton reading Dylan Thomas by comparison.

I tried to give it a chance. I found a full-length version of Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway, which has one of the most beautiful and best-known opening passages in British fiction, read by ‘Ava’, one of the British voices, and I gave it a good go. There are six hours and nine minutes of Ava reading Mrs Dalloway and I determined to last as long as I could.

I gave up after about ten traumatic minutes. It was excruciating. The randomness of the stresses and intonation left me so disorientated that when I stood up I nearly fell over. I was hearing the right words in the right order but the inflections were so weird I could barely understand them. What sounded like it should make perfect sense made no sense whatsoever, a bit like one of Dominic Cummings’ Twitter threads.

It didn’t take long before it was glaringly obvious what the recordings were missing: a soul, the faintest presence of humanity. A bit like one of Dominic Cummings’ Twitter threads.

I can see the benefits of auto-narration. The increased availability of books in a format to which more and more people are turning can only be a good thing.

Yet however technically perfect an auto-narration might be with a consistent accent, regular pacing and a complete absence of stumbles, those are just the building blocks of a plausible reading. A musician practises scales because technique facilitates self-expression and those scales are the building blocks. You wouldn’t buy an album of chromatic scales, but that’s effectively what these recordings are giving you.

Unnatural as they sounded, the voices were too technically perfect. They never cracked, never strained slightly towards the end of a long sentence and never even paused for breath.

It was passionless and soulless, there was no tension, humour, warmth or compassion. It was the antithesis of everything literature is and should be, like your satnav reciting Hamlet’s soliloquies.

Speaking as a listener, author and narrator of audiobooks, I have assembled what I think are the key ingredients for producing a successful one.

Be clear, take your time, react to the text as you go and, perhaps most importantly, don’t go too heavy on the chilli oil in Wagamama’s on your lunch break.

Not an issue for the auto-narrators, of course, but the fact that it isn’t is exactly why they aren’t working.