It is something of an understatement to say that for years after the second world war, Germany had a bit of an image problem. The legacy of history’s most murderous and politically revolting regime will do that.

As a newly cleaved nation set about rebuilding itself, its cultural representation in a new global age was not particularly high on the agenda. While Elvis Presley wiggled his hips towards unprecedented stardom and James Dean pouted and snarled his way to cinematic immortality, the Germanies were preoccupied with more pressing matters like the complete rebuilding of a national psyche. The world could wait.

Then in 1960 came The Magnificent Seven, John Sturges’ remake of Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai relocated to Mexico. It redefined the cinematic western. The Magnificent Seven, all flawed protagonists, nuanced morality and stirring Elmer Bernstein score, remains one of cinema’s landmark moments.

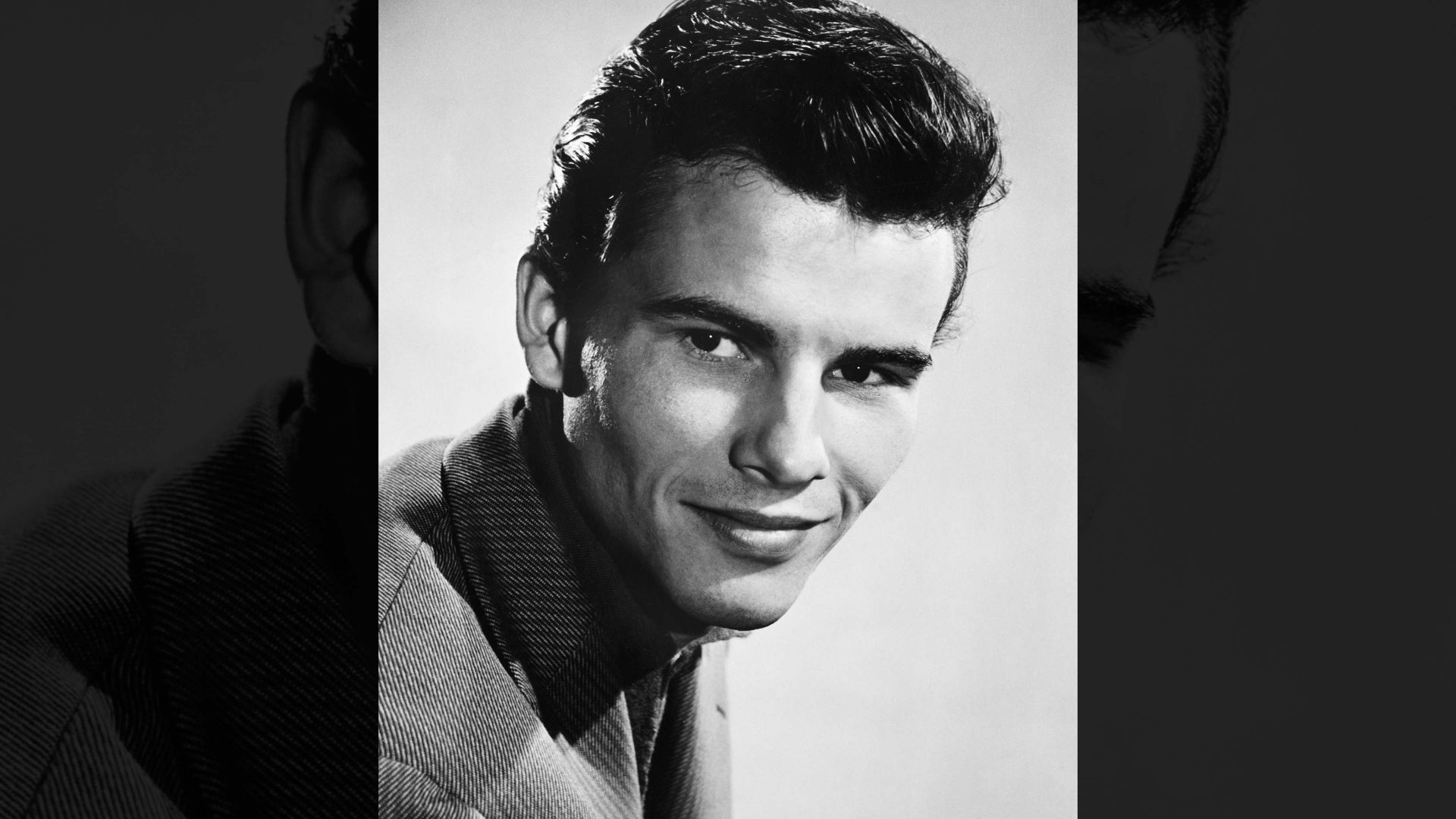

The film brought together a stellar cast including Steve McQueen, James Coburn, Eli Wallach and Yul Brynner, while making his mainstream Hollywood debut as Chico, an impulsive wannabe gunfighter and youngest member of the gang, was a chiselled-featured, dark-haired actor with classic movie star looks.

The 27-year-old Horst Buchholz had recently arrived in the US as the “James Dean of Germany” and he burst on to the screen, seemingly destined for stardom. More than holding his own among that exalted cast, Buchholz had a magnetic screen presence. Kids across Europe and America wanted to be Chico in their schoolyard games and Buchholz was linked romantically with a string of Hollywood starlets, all promising signs for the first German to break through in the new age of celebrity. Horst Buchholz was handsome and gifted, but most of all Horst Buchholz was cool.

Perhaps the level of expectation weighed too heavily on him because that promise would never truly be fulfilled. He made only four major films in Hollywood, each seeing his star fade a little more. James Coburn had noticed something when making The Magnificent Seven, writing later that director John Sturges “was enamoured. He shot a lot of film of Horst. I thought he missed there, but that was the one place. I think everybody else was cast quite well”.

The following year Billy Wilder placed Buchholz opposite James Cagney in One, Two Three, a dark comedy set in contemporary Berlin in which Cagney plays a Coca-Cola executive who learns that his boss’s daughter, whom he is supposed to be chaperoning, has just eloped with a communist East Berliner played by Buchholz. Back on home territory, Buchholz earned wide praise for his performance, not least from Wilder himself who announced that “Horst is the best young leading man in the world today. He’s a real international star and has all the qualities that made James Dean box office”.

Yet Buchholz would never truly be box office and it is hard to define why. He certainly had the looks and also the acting chops to back up his screen charisma, yet somehow these perfect ingredients never nailed the recipe.

It could have been the roles he accepted and rejected – playing Gandhi’s assassin in Nine Hours to Rama, a decent performance in a mediocre film, all but ended his career in the US, and turning down the part that eventually went to Clint Eastwood in A Fistful of Dollars might not, in hindsight, have been the best career move.

He had also been forced to turn down the role that went to Omar Sharif in David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia because it clashed with the filming of One, Two, Three, while his refusal to anglicise his name added to a list of what-might-have-beens. Wrapping his car around a tree in 1961 necessitating a long stay in hospital just when his career seemed to be building momentum didn’t help either.

Yet Buchholz enjoyed enough success to have earned a greater legacy than he enjoys today, not least for his pioneering role in the postwar cultural rehabilitation of Germany and Germans.

Born the year Hitler came to power, the young Buchholz was, like most Berlin children of his generation, evacuated to the relative safety of Silesia to escape Allied air raids. By the end of the war he was in a children’s home in the Czech countryside from which he hitchhiked back to a shattered Berlin he would barely recognise, a bomb-ravaged city whose traumatised inhabitants were now divided into sectors run by the four victorious allied powers.

He forsook regular education in favour of the stage, making his stage debut in 1947 in an adaptation of Emil and the Detectives and before long was supplementing his stage roles with small parts in films and voice work dubbing foreign films into German. It was when he was spotted at Berlin’s Schiller Theatre by the film director Julien Duvivier that he began to shine, his first major screen role coming in Duvivier’s 1954 Marianne de ma jeunesse. A year later he appeared in Himmel ohne Sterne, a performance good enough to secure the Best Actor award at the Cannes Film Festival.

He became the personification of disaffected youth in 1956’s Die Halbstarken, effectively a German Rebel Without a Cause, to earn his first comparisons with Dean, but it was his performance opposite John Mills in Hayley Mills’ screen debut, the Cardiff-set Tiger Bay in 1959, that hinted at appeal outside Germany and earned him his break in the US.

After Hollywood he returned to Europe and took roles in a string of forgettable films labelled “Europuddings”, tales churned out by crews from several countries that struggled for narrative identity. He played the lead in a clumsy telling of the Marco Polo story as famous faces like Orson Welles and Anthony Quinn loomed up en voyage, but big names couldn’t save a bad movie. “Mr Buchholz should never have left Venice’’ was one reviewer’s opinion.

He travelled the continent with similar productions, playing Cervantes and Johann Strauss among others, but the matinee idol looks faded with each. It took 1997’s Life Is Beautiful to nudge Buchholz back into the international spotlight as the ageing concentration camp doctor whose obsession with puzzles means he misses a chance to save Roberto Benigni’s lead character.

Missed chances were the story of Buchholz’s life, as if there was an uncertainty at his core making him mistrust the extent of his talents. Maybe there was a hint of that in an interview shortly before his death when the actor who was married to the French actress Myriam Bru for almost half a century revealed his bisexuality. Perhaps this was a burden too far for the man who made Germans cool again.