When he arrived in the USA during the summer of 1979, Herman Brood sensed he was on the crest of something. In the previous two years he’d released two albums in his native Netherlands that both went gold and now he was in the country that had beguiled him ever since he “saw Johnny Weissmuller wrestling crocodiles and heard Little Richard do Slippin’ and Slidin’.”

This was New York City and he was waiting to go on stage at the Bottom Line with his backing band Wild Romance, a heady mix of adrenaline and alcohol coursing through him.

He’d tried to rein himself in at the soundcheck but even in an empty room with the house lights on, the floor still sticky with last night’s spillages and that familiar combination of stale beer, cigarettes and bleach in his nostrils, he could barely contain himself.

New York. The Big Apple. The big time.

He looked around the dressing room with its ripped-open sofa, walls covered in graffiti, and beer bottles clustered on the table. A showcase, their manager Koos van Dijk had called it, spending most of the day on the phone to record companies and journalists, trying to sell them Herman Brood as the most exciting thing to come out of Europe since the Pistols. A Dutch guy pitching a Dutch singer was a hard sell here but if anyone could pull it off, thought Brood, Koos could.

Nobody had ever shown much faith in him until the day in 1976 when, before a gig with Cuby and the Blizzards in Winschoten, Brood had been about to shoot up in the dressing room but dropped his needle. He was rummaging in the waste paper basket for it when the door opened and in walked Koos, who owned the place.

Many people might have been shocked walking in on junkie desperation. After all, Brood’s drug use had already seen him kicked out of the Blizzards back in 1969 when the record company got wind of the keyboard player’s habit. But instead of turfing him out on to the street, Koos had got down on his hands and knees and helped him find that lost needle. A few months later he sold the club to bankroll Brood’s fledgling solo career.

The true spirit of rock’n’roll is what van Dijk recognised in Herman Brood and he was happy to put his money where his mouth was. The album Street appeared in 1977, followed by Shpritz a year later. Shortly before departing for the US, Brood had starred alongside Nina Hagen and Lene Lovich in the new wave musical Cha Cha. Momentum was building.

Yet before that meeting in Winschoten, a directionless Brood had been drifting through an aimless haze of drug addiction and alcoholism. Now 32, he was still a drug addict and alcoholic – but one with a purpose.

He’d joined his first band The Moans while at art college in Arnhem, pounding the keys during long sets of R’n’B classics for American GIs that stretched late into the night. While the relentless gigging was the perfect way to learn stagecraft, the amphetamines Brood needed to last the pace were the first step on a long journey into pharmaceutical excess.

That 1969 sacking after two years with Cubby and the Blizzards prompted a murky period during which Brood spent time in prison for burglary, drug dealing and, if his claims in US newspaper interviews were to be believed, bank robbery.

A spell dealing opiates in Turkey ended when he ran out of money, prompting a move to Israel and a year working in a copper mine – “I slept in the wadi around Eilat and hustled opium to American hippies” – before returning to the Netherlands for a brief reunion with the Blizzards and the chance meeting with Koos van Dijk that set him on the road to America.

His criminal record had posed problems ahead of the tour and it took six record company lawyers, a hefty bond and solemn guarantee of good behaviour in front of the American consul in Amsterdam to secure a visa. Promising to eschew his usual diet of Class A pharmaceuticals for the duration of the tour, Brood declared he was happy sticking to booze.

“I am an alcoholic and proud to be one,” he’d told an interviewer that afternoon. “I understand alcoholism is legal here.”

The band hit the stage, Brood running on and grabbing the mic stand with both hands and launching headlong into Rock’n’Roll Junkie. Eyes closed and singing his heart out, he screamed his lyrics over the high-energy sound of the tightest band with whom he’d ever share a stage.

“I have stories to tell, stories about me and what’s happened to me in my time,” he’d told the interviewer, and here he was, unleashing those stories on a new audience in the country he’d dreamed of ever since hearing Little Richard bursting out of the radio as a boy back in Zwolle.

The Bottom Line was barely a third full that night. Most of the audience remained in the shadows. While the man from the New York Post described the show as “one of the most explosive sets of rock’n’roll I’ve ever seen” the New York Times was less generous.

“An inept show,” it declared, “sloppy, false and embarrassing in tone, derivative in music.”

Brood was crestfallen and immersed himself in drink and drugs. The tour descended into a series of increasingly shambolic shows in front of small, half-interested crowds. Subsequent recording sessions for the new album Go Nutz were a disaster, the American producers refusing to work with the Wild Romance rhythm section and insisting on local session players instead. Brood’s willingness to accommodate the idea spelled the end of the original line-up and produced a lukewarm album, shorn of the raw energy of their live shows.

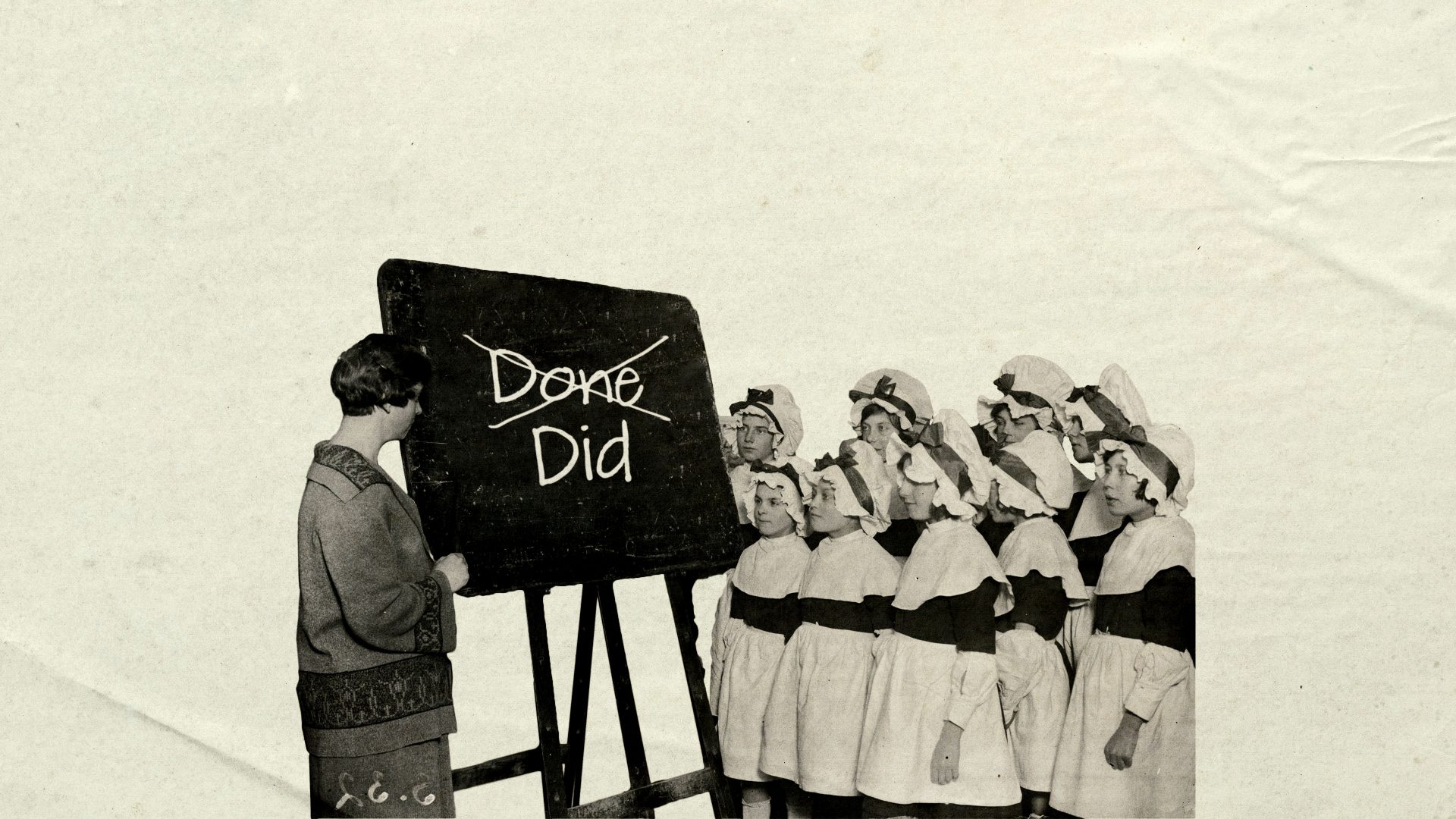

Brood kept making music for the next two decades, appeared in theatre and films and established himself as a painter of large canvases in bold colours, mentioning in interviews how his art teacher at school had told his parents: “I could become anything I want to be, except an artist”. But the momentum that had carried him across the Atlantic was gone. What truly kept him in the public eye was a hedonistic lifestyle conducted with an unbridled openness about drug use.

When he reached middle age the abuse his body had taken began to take its toll. There were spells in rehab with mixed results until the summer’s day in 2001 when Brood jumped from the roof of the Amsterdam Hilton carrying a note in his pocket addressed to his wife that read: “Carry on as I did and don’t grieve! Make it a party.”

Partying implies joy, however, and whatever Herman Brood was looking for, joy played little part in it.

“I’ve always been fascinated by the dark and forbidden,” he said in 1979. “I need the fever in life. I can take the consequences, like jail, but I am looking for kicks, kicks, kicks all the time.”