First there was Mondeo Man, then Worcester Woman. In Labour’s wilderness years in the 1980s and 1990s, pollsters defined the party’s challenge in terms of the middle-income swing voters it needed to attract.

Labour has double the problem today. It must simultaneously target two distinct sets of voters with very different political values. Meet Jenny and Joe, the voters who will decide whether Keir Starmer can become prime minister.

Jenny is in her late twenties. She is a graduate who has started to climb the professional career ladder. She is a liberal-minded internationalist who regrets Brexit, fears climate change and welcomes the impact immigrants have had on her community. She voted Labour at the last election, though some of her friends voted Liberal Democrat or Green.

Joe is in his late fifties. He left school at 16 and, apart from brief spells when he was unemployed, has done manual jobs throughout his working life. The years of austerity have been tough for Joe and his family, living in one of the struggling, ex-industrial and once-solidly Labour that elected Conservative MPs in 2019. He worries that measures to tackle climate change will make life even tougher. He feels that Britain’s elite has let down people like him. Like many in his town, he voted to leave the EU in 2016 – and Conservative, “to get Brexit done”, in 2019. Some of his friends voted UKIP in 2015.

Behind the scenes, arguments are raging around Keir Starmer over what to do: appease Joe or champion Jenny. For the moment, the “Joe” faction is ahead. Starmer has retreated from his past support for the European Union and freedom of movement, and is seeking to avoid tough choices on climate change. This faction hopes that at the next election, this approach will allow Labour to recapture the Red Wall seats, without alienating Jenny. They believe that they can count on Jenny staying loyal, come what may, as her dominant concern will be to kick out the Tories, however far Starmer tacks to the Right.

Other Labour figures, including some in the shadow cabinet, think the opposite. They want Labour to hold firm to its liberal, pro-European principles and green ambitions. They side with Jenny and fear that to appease Joe would be to betray their values. They hope that Labour will be able to expand its appeal to progressive Britain, and that the departure of Jeremy Corbyn will be enough to bring Joe back into the fold.

Both sides are wrong. To win the next election, Labour must actively appeal to both Joe and Jenny. To target one and not the other is a recipe for defeat. To be sure, it’s a tough problem. To make Keir Starmer prime minister, at least at the head of a minority government, Labour must aim for 40%-plus. To reach this target it needs both Jenny and Joe.

This analysis explores the reasons for Labour’s twin challenges – and how to tackle them. It draws on fresh evidence of public attitudes to two of the most divisive issues, Europe and immigration. It argues not only that Labour must appeal to both Jenny and Joe – but that it can.

Understanding Labour’s predicament is the starting point for tackling it. How come that today’s Labour Party needs the support of not one kind of voter, occupying the middle ground of British politics, but two very different kinds of voter?

There are two sets of reasons. The first relates to the past, and the way Britain’s electorate has changed. The second relates to the future, and the changes yet to come.

First, the past, and how we got here. Back in the early 1980s, most people of all ages in professional jobs voted Conservative. “Jenny” in those days, born in the mid-1950s and graduating in the 1970s, was a home-owning beneficiary of a number of Margaret Thatcher’s policies. This Jenny did not think of herself as especially right-wing; but she feared what a left-wing Labour government might do.

In contrast, “Joe” in the Thatcher era – a manual worker born in the mid-1920s – voted Labour, as he had done every election since his first, in 1950. In the Tory landslide in 1983, some of Joe’s friends switched to the Conservatives; but most stayed loyal to Labour. As trade union members in large factories, mines, mills and shipyards, they believed in solidarity and collective action as the way to a better life.

Since those days, “Jenny” and “Joe” have swapped parties. The Tory Jenny of the 1980s had become the Labour Jenny by 2019 – while the Labour Joe who couldn’t stand Margaret Thatcher has been succeeded by the Conservative Joe who put his faith in Boris Johnson.

The stories of Jenny and Joe reflect the transformation of Britain’s economy, the decline in the Red Wall towns of heavy industries with their powerful trade unions, the growth of new technology and the expansion of higher education in so many big cities. The old social-class divide (working-class Labour / middle-class Conservative) has been replaced by new divides of age and education (graduates under 40, heavily Labour and pro-European; non-graduates over 50, heavily Tory and pro-Brexit).

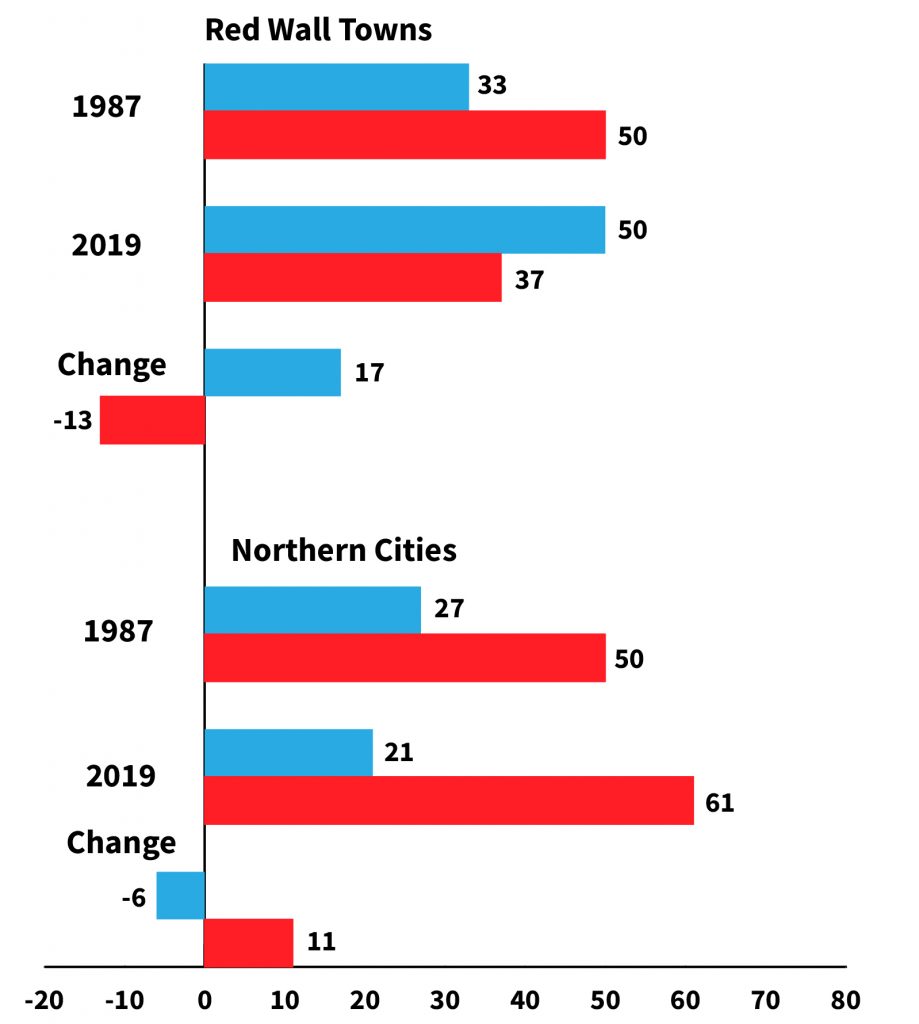

The impact of the trends represented by “Jenny” and “Joe” can be seen in the “Red Wall” towns captured by the Conservatives in 2019 – and in Labour’s growing dominance in the big cities in the same regions with established universities. The following table compares the way they voted in two general elections, 32 years apart, which both produced similar nationwide results – Conservative leads of 12 percentage points in the national vote.

Regaining the Red Wall seats is crucial to Labour’s chances of winning the next election. They comprise a large share of constituencies with small Conservative majorities. Regaining them, however, is not enough. For Labour to win outright, it needs to gain at least 120 seats (boundary changes will affect the exact number). That’s highly improbable. Labour does not need to pick up that many seats to put Keir Starmer into Downing Street. Labour may not even need to be the largest party to achieve that. But to have anything more than a brief, precarious time in office, Labour needs to gain at least 80 seats. It cannot do this by reversing its Red Wall losses alone. It needs the support of Jenny as well as Joe.

In principle, it should be possible for Labour to appeal to both – and potentially catastrophic not to try. Voters are more volatile than they used to be. In the 1960s almost 50 per cent of voters told the British Election Study that they identified “very strongly” with a political party. BES’s post-2019 research puts the figure at just 14 per cent. The stories of Jenny and Joe, past and present, are part of that saga. Their loyalties are less fixed than those of their parents and grandparents. They have switched sides before and could do so again. Joe could be open to changing his vote – but so could Jenny.

This brings us to the second reason for Labour to target Jenny as well as Joe. She is the future. Britain’s “Jenny” population is growing, while the number of “Joes” is steadily diminishing. And voters like Jenny do not live only in big cities. They are to be found in Labour-Conservatives marginals in the suburbs and in commuter towns where decades of Tory hegemony could be threatened. Some – not many, but in some places enough – live in Red Wall towns. Labour cannot win future elections by winning back Joe alone.

(Any Conservative reading this should note that their rejection of Jenny and her values could cost them dear in years to come, as the impact of these demographic trends grows. The Tories might hope that as Jenny starts a family, her passion for liberal causes will fade. That hope might well be dashed. In recent decades, the British Social Attitudes surveys have charted attitudes on variety of values including race, abortion, civil liberty and gay rights. Britain has become steadily more liberal. This is not because many people have changed their minds, but because the older opponents of reform have died out, while the once-youthful supporters of reform, especially graduates, have retained their liberal outlook as they have grown older.)

The long-term dangers of Labour taking Jenny for granted are even greater than the short-term costs. Its status as Britain’s dominant progressive party could be challenged. In the short-to-medium term, the risk is that in seat after seat, the Conservatives will hold on because too many voters like Jenny vote Liberal Democrat or Green (or nationalist in Wales and Scotland), because they feel that Labour has drifted too far to the right. As the number of Jennies grows, Labour needs to fight to hang on to them.

So Labour needs to win back Joe and hold on to Jenny. How?

A good starting point is the recognition that few of us are as obsessive about politics as party activists. Except at the height of an election or referendum campaign, voters are concerned mostly with practical day-to-day concerns. Research by Deltapoll for the Tony Blair Institute finds that there is a common ground shared by voters like Jenny and Joe – by young and old, graduate and non-graduate, socially liberal and socially conservative. Their agenda includes prompt health care, preventing poverty, decent pensions, good schools, secure jobs, fair taxes, safe streets and properly-funded social care.

That common agenda leaves plenty to argue about. However, the axis of that argument has changed in recent decades. Today’s Jenny and Joe, having shed the class loyalties of their past equivalents, do not have firm ideological convictions. It is values that divide them, not the old contest between socialism and capitalism.

All this is well-trodden territory, especially since the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of Soviet communism. Except for a minority of ideological purists on Left and Right, the great conflict between socialism and capitalism, which framed so much of twentieth century politics, is over. As the political landscape changed, party strategists developed concepts such as Worcester Woman and Mondeo Man to plan how to reach target voters – and often to persuade outspoken activists within their own parties that practical competence matters more than ideological purity. The good news is that if this was all that Labour (or the Conservatives) needed to do, they should be able to appeal to both Jenny and Joe.

The bad news is that there is a second challenge to tackle, and it’s far tougher. The design of a common day-to-day agenda is a necessary but not sufficient condition for any party seeking to win the votes of both Jenny and Joe. They will be wary of any party that they think trashes their values. Jenny is unlikely to embrace an aggressively nationalist party, however much she likes its economic and social policies, while Joe will continue to reject any party that he thinks sells Britain short. In short, they want two things: a party that they believe will improve their lives – but also one that respects their values.

Is there a way for Labour to span the Jenny /Joe divide on values and appeal to both? Not completely: it is hard to see many people who took part in the anti-Brexit “People’s Vote” marches voting Tory any time soon. Nor can Labour expect to attract many former UKIP activists. However, once again we need to distinguish between the minority who are obsessive about their politics and the majority who are not.

Jenny and Joe belong to the non-obsessive majority. Jenny opposes Brexit, and would vote for Britain to rejoin the EU, given the chance – but she does not spend every waking hour grieving at the result of the 2016 referendum. Joe is glad that Britain has left the EU; but now it has happened, he is more concerned about normal political issues such as jobs, prices, crime and health care.

All this creates an opening for Labour to compete for the votes of both Jenny and Joe without insulting or ignoring the values of either. Labour does not need to take Jenny for granted, as the party seems to be doing now. Nor does it need to pick a fight with Joe’s attitude to the EU, as the party did in 2019.

However, Labour won’t be able to square this circle by maintaining its current vow of omerta on Brexit. Such a stance won’t survive scrutiny in a general election campaign. So what can Labour say? Its best hope is to redefine issues such as Brexit and immigration as social and economic challenges, rather than as tests of national identity. Put another way, it is to do what successful Labour governments have done in the past – promote progressive values as practical improvements to everyday life.

Labour’s own electoral history shows that this is not just a general, national truth. One specific local story from six decades ago has relevance today. In 1964, Labour ended 13 years of Conservative rule by gaining more than 60 seats. Smethwick, in the West Midlands was an exception. Following an ugly, overtly if unofficial, racist campaign, the Tories gained the seat on a seven per cent swing. However, at the following general election 18 months later, Labour recaptured the seat on an even bigger swing: almost eight per cent.

As the two elections were held so close together, we can be sure that broadly the same people voted in both elections. It is unlikely that, uniquely in Britain, they had suddenly become fiercely anti-immigration in 1964, only to revert to a more liberal stance in 1966. The point about Smethwick was that the first election was framed locally as a contest about race, while the second election was fought on the same dominant issues as in the rest of Britain: jobs, prosperity and a secure future for families needing to make ends meet..

The lesson from Smethwick is that if an election is fought as a culture war, Labour’s support can crumble in the face of right-wing populism. The party does far better when election battles are about economic and social progress. How can this principle be applied to the challenge of appealing to both Jenny and Joe?

Take Brexit first. Applying the lessons of successful past leaders, Labour would argue that Brexit is not going well and needs to be fixed. It would offer a progressive/practical approach that both Jenny and Joe could approve, or at least tolerate: pro-European but framed as a practical way forward, not as a disruptive, doctrinal imperative.

Such an approach would include amending the UK’s relations with the EU in ways that boost trade, jobs and investment. This might involve the UK accepting certain EU rules, for example on food safety and product standards, without overturning Brexit. It would be in line with what many Leave campaigners proposed in the 2016 referendum: ending membership of the EU while retaining those aspects of the Single Market and Customs Union that benefited British workers, consumers and businesses.

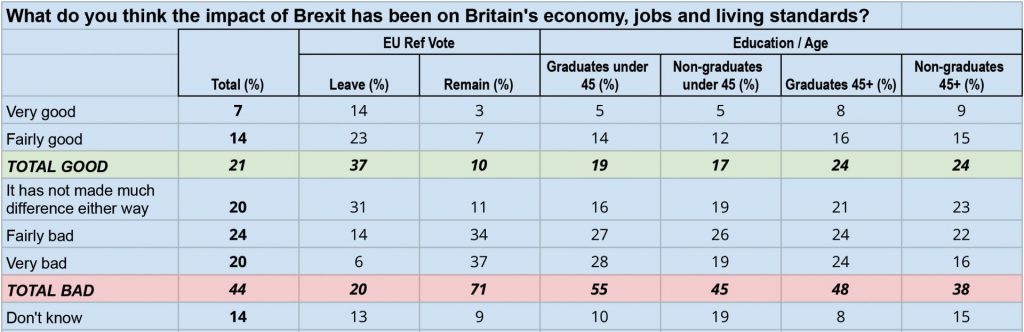

How would this go down with voters on the two sides of the Jenny-Joe divide? Deltapoll surveyed more than 2,000 adults throughout Britain in early March. These are its figures for questions about Brexit and the economy.

The first thing to note is that there is a two-to-one majority, among those who take sides, saying Brexit has been bad for the economy, society and living standards. Even among those who voted Leave, just 37% think Brexit has benefited our economy. We can assume that among the most passionate Leave voters, the number saying “good” is more than that – and that among more “normal” Leave voters such as Joe, the proportion is less than 37%. (By the same token, the number of “normal” Remain voters saying Brexit has been bad for the economy is likely to be less than 71% – but still almost certainly a clear majority.)

That view is supported by the figures for the broad age and educational categories – the main demographic influences on people’s views and votes. There is some difference between the “Jenny” group (graduates under 45) and the “Joe” group (non-graduates over 45), but in both, the number saying Brexit has been bad for Britain outnumber those saying it is good for Britain.

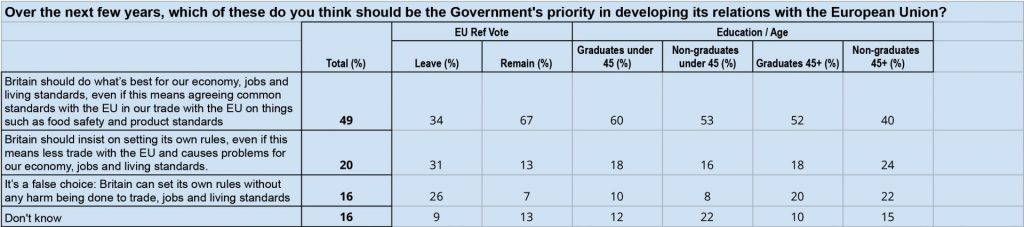

As the following table shows, this creates an opening for a Labour policy on Europe that could appeal to Britain’s Jennies and Joes. Labour would seem to have a real opportunity to point to the harm Brexit has done – not least by identifying the particular problems facing local businesses, workers and consumers in seats with small Conservative majorities.

These figures indicate the advantages of framing the debate about Europe in terms of economic security rather than national identity. Among voters generally, agreeing common standards with the EU is supported by more people (49%) than the two more hardline pro-Brexit options combined (36%). More to the point, it is the preferred option of a large minority of Leave voters (34%) and non-graduates over 45 (40%). In short, it is a policy that many Joes could back. Only one in five voters – and just one-in-three Leave voters – are prepared to sacrifice prosperity in order to insist on Britain’s right to set its own rules. Given that the Government’s own Office for Budget Responsibility makes clear that Brexit in its current form carries sufficient economic costs, the pragmatic argument for common rules and standards is one that Labour can win.

At the very least, such a policy would no longer be a Brexit barrier to voting Labour, as it was for many Joes at the last election. At the same time, it would appeal to more Jennies than a policy that accepts every feature of Brexit and denies the case for co-operating with our European neighbours to repair the damage it has done.

As for immigration, Joe’s other huge fear about Labour in recent years, much of the debate at the time of the 2016 referendum concerned fears of Britain being swamped by EU “welfare tourists” not seeking work but jumping the queue for health care and social housing. Retorts that this was a travesty of reality cut little ice. Many voters thought that it was a consequence of British membership of the EU.

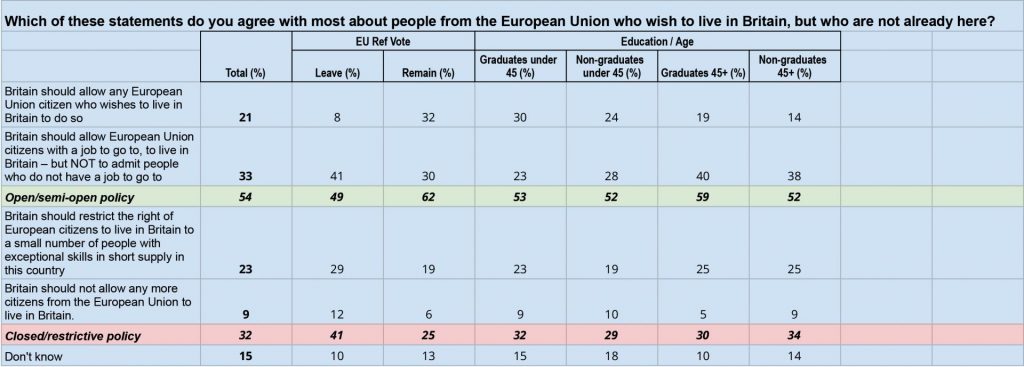

Now Brexit has happened, debates about immigration can be framed differently. Once again, the key to appealing to both Joe and Jenny is to steer clear of an unwinnable culture war. Instead, Labour could apply the general principle that our rules should be designed to achieve economic and social benefits and tackle the fears of insecurity, real or imagined, flowing from a policy of unrestricted immigration. The following table suggests that an explicitly work-related policy could work.

There is plainly a clear majority for a more open policy; and, significantly, it is the preferred option for every group – even Leave voters, who back it by 49-41%. One of the (many) failures of the pro-EU campaign in the Brexit referendum was to allow the term “freedom of movement” to apply to people regardless of their economic status. Polls ahead of the referendum found that membership of the European Union was widely believed to cause a large amount of welfare tourism – people coming to the EU specifically to live on benefits. The facts – that “freedom of movement” is an economic concept, specifically about crossing borders in order to work, and that the number of EU citizens receiving unemployment benefits (after losing their job) was negligible – were elbowed aside.

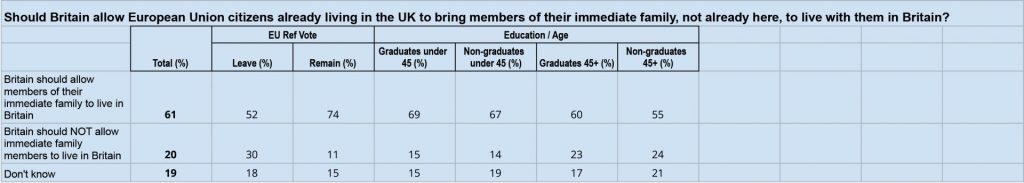

The figures above showed that, properly interpreted and enforced, “freedom of movement” could be a popular policy that appeals to both Jenny and Joe. This is even more true about a related immigration policy: admitting the members of the immediate families of EU citizens already living in the UK:

Once again, the key to bridging the cultural divide on immigration is to recast the issue as an economic and social challenge. Jenny and Joe have different sentiments about the role immigration has played in British life in recent years, but not such different views about the people that Britain should admit in the years ahead. Both could be persuaded to support a progressive/practical policy – one that is seen to aid rather than threaten economic security – as long as Labour can convince them that it genuinely intends to make it stick and is sufficiently competent to succeed. Tony Blair has suggested that the introduction of ID cards could help not just to enforce such a policy, but to reassure voters that it would work.

These suggestions will doubtless offend those with passionate views on both sides of the Brexit and immigration divides. But many Labour and Tory activists were equally opposed to concepts such as Mondeo Man and Worcester Woman. Activists saw elections as a clash of ideologies, not as the need to woo floating voters in the middle ground.

Keir Starmer has near-total control over his party. Jeremy Corbyn is out in the cold; his allies have been marginalised. Ideologically fervent activists can safely be ignored. But it will not be enough to offer the negative reassurance that Labour is no longer beholden to the hard Left. Starmer needs his own tune for his supporters to sing. Generalities about fairness will not be enough. Clarity, courage and a fierce commitment to practical policies on issues such as Europe and immigration – and also such huge challenges as climate change and the future of public services – are vital.

So is competence. Other recent surveys have found that the greatest weakness in Labour’s overall reputation, especially among older non-graduates such as Joe, is the perception that it is incompetent. Banishing that weakness is a massive task, beyond the scope of this report. The point here is that failure to do so makes Labour unelectable, whatever it says in order to hold onto Jenny and win back Joe.

But if it can persuade enough voters that it would run Britain well, then it can frame its approach to even the toughest issues, such as Europe and immigration, in ways that bridge the divide between Jenny and Joe.

Labour has succeeded in the past by marrying its progressive principles to practical policies that voters felt would give them greater security and which they trusted the party to implement. Think of the Attlee government and the creation of the NHS; or the social reforms of Harold Wilson’s administrations, or New Labour’s record, from the minimum wage and Sure Start, to health spending and tax credits.

However, never before has Labour had to attract two distinct groups of swing voters as different as. Jenny and Joe. They present the party with its toughest challenge. Its best chance is to inspect its own history with clear eyes, an open mind and confidence in its basic values. Then it has at least a chance to win the next election as a contest about fairness, prosperity and security – rather than lose it by surrendering to the culture-war fallacy that, faced with the differences between Jenny and Joe, it must take sides.