In the early afternoon of January 29, 1948, Henri Cartier-Bresson was led onto a verandah at Birla House, a mansion in New Delhi, and introduced to an elderly man in white robes sitting up on a wicker daybed. Mahatma Gandhi had just broken a fast undertaken in the name of peace between Hindus and Muslims, so was a little more frail than usual, but he greeted the photographer cheerfully and invited him to sit.

Cartier-Bresson had come to photograph the figurehead of Indian independence for Magnum, the picture agency he’d co-founded the previous

year with three other photographers including Robert Capa. Magnum was a

new kind of agency, selective in the photographers it commissioned, preferring those who saw something more through their viewfinder than the straightforward preservation of events on film.

The founding of Magnum came at the dawn of a new era in photojournalism, an age when people turned in their millions to picture-heavy magazines like Life and Paris Match to learn of key events around the world and the cultures that produced them. It was the latter Cartier-Bresson was interested in; he was in search of the essence of a nation newly independent of British occupation and still raw from the febrile partition of Hindu and Muslim that had led to thousands of deaths.

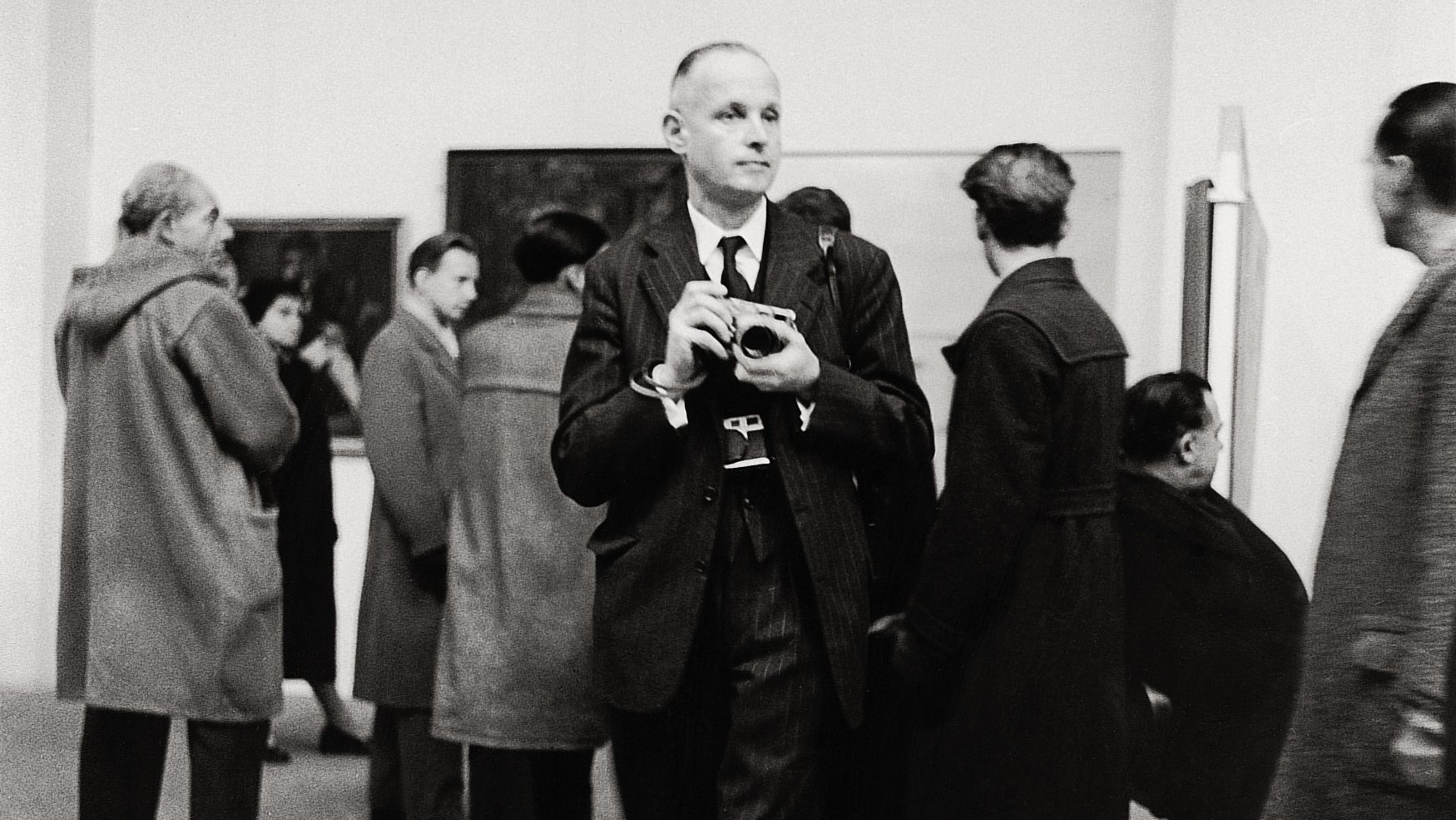

As they talked, Cartier-Bresson photographed the 78-year-old Gandhi attending to some paperwork, slipped into the background as a succession of visitors filed past the supine figure, then followed him on a visit to a Muslim shrine. Back at Birla House, as Gandhi rested, the photographer showed him the catalogue from his solo exhibition staged the previous year at MoMA in New York. Gandhi leafed through the pages wordlessly until he

reached an image of a man in a raincoat walking tentatively past a horse-drawn hearse.

“What is the meaning behind this picture, please?” asked Gandhi, and Cartier-Bresson explained the figure was the poet Paul Claude, a man consumed by the spiritual implications of life and death. Gandhi paused for a moment, looking at the photograph.

“Death,” he said quietly, almost to himself, before repeating “death, death.”

Almost exactly 24 hours later, as he walked from the verandah to a prayer garden nearby, Gandhi was murdered by a Hindu nationalist. Instead of a

gentle, immersive documentary assignment, Cartier-Bresson found himself suddenly at the heart of world events.

He photographed Indian prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru announcing Gandhi’s death, then documented the funeral and the transfer of Gandhi’s

remains to the Ganges. He was characteristically all-seeing, capturing the shock and grief of crowds lining the streets, ordinary Indians reeling at the violent end of their ambassador for peace. Among the most memorable photographs is one of Gandhi’s secretary Brij Kishen watching the first flames flickering from the funeral pyre, his face a picture of heart-wrenched grief.

Cartier-Bresson had a knack of witnessing some of the 20th century’s key episodes – the Spanish civil war, the German invasion of France, the end of Gandhi, the Chinese revolution, the 1968 uprisings in Paris – yet he was no newshound. What he sought was images á la sauvette, most commonly

translated as “the decisive moment”, what he described as “the simultaneous recognition in a fraction of a second of the significance of an event, as well as the precise organisation of forms that give that event its proper expression”.

Believing that photography gave you one chance and it had to count, he was appalled by the idea of rapid-fire shooting, seeing it as no more than pointing the camera and hoping for the best. He never used a tripod, a flash or reflectors and worked almost exclusively through a 50mm lens, the simplest equipment with which he’d wait for the image he wanted to present itself – a colleague with him at the 1968 Paris uprising observed that Cartier-Bresson took just four photographs in an hour.

“Photography as I conceive it, well, it’s a drawing,” he said, “an immediate sketch done with intuition that you can’t correct. Life is very fluid, sometimes the pictures disappear and there’s nothing you can do. You can’t

tell the person, ‘Please smile again. Do that gesture again’. Life is once,

forever.”

Descended from Charlotte Corday, Jean-Paul Marat’s assassin, Cartier-Bresson was born into a wealthy merchant family whose father believed in almost obsessive frugality, to the point where young Henri grew up believing he was poor. A keen sketch artist in his youth, he went on to study art and literature at Cambridge University, had a spell in the army and travelled to Africa, where he almost died of blackwater fever. It was while recuperating in Marseilles that he acquired his first Leica, the camera he favoured for the rest of his life, where he “prowled the streets all day, feeling very strung-up and ready to pounce, determined to ‘trap’ life; to preserve life in the act of living”.

During the German invasion he became a corporal in the French army’s film and photography unit but was soon captured, spending nearly three years in a prison camp from which he escaped to document the occupation for the Resistance. Then, after the war, he co-founded Magnum.

By the dawn of the 1970s Cartier-Bresson felt increasingly that he had said everything he’d set out to with his camera, drifting more towards the drawing and sketching he’d studied in his youth. Right up until he was almost 90 he would haunt the galleries of Paris, sketching the paintings, utterly absorbed in form, shape and colour.

Engrossed in his task he was oblivious to the people snapping pictures of him as he worked, not because they’d recognised Henri Cartier-Bresson but because he was a funny old man in a raincoat perched on a shooting stick with sketchpad and charcoal trying to emulate the great masters. As they nudged each other and smirked, these passers-by couldn’t have known that this was a man who had photographed Matisse, Braque and Giacometti, and sat with the surrealists in Paris cafés listening to André Breton philosophising. They couldn’t have known either that, elderly as he was, Cartier-Bresson was still as obsessed as ever by what made the perfect image; its components, its atmosphere, its sense of being right there in the

moment.

“I enjoy shooting a picture, being present,” he said in 1971. “It’s a way of saying, ‘Yes! Yes! Yes!’, like the last words of Joyce’s Ulysses, which is one of the most tremendous works ever written. Photography is like that. It’s ‘yes, yes, yes’. And there are no maybes. All the maybes should go into the trash,

because it’s an instant, it’s a moment, it’s there. And it’s the respect of it and

tremendous enjoyment to say, ‘Yes!’ Even if it’s something you hate. ‘Yes!’ It’s

always an affirmation.”