When the artists Helen Frankenthaler and Robert Motherwell set out in 1960 on an extended honeymoon across Europe, they were unprepared for conditions somewhat less sophisticated than those of their affluent American upbringings. Frankenthaler, a prolific letter-writer as well as painter, complained to one friend about the villa that they had rented in Alassio, on the Ligurian coastline, not far from the French border, and about the little, overcrowded town itself.

“We’ve sort of had it,” she lamented, listing “a small nightmare of things that don’t work – (john, stove, lights, just those little things)”.

Her large painting that bears the name of the resort is as messy as the holiday, vividly reflecting both the bright, natural beauty of Alassio and not a little turmoil. A great wave appears to break over wet sand, as the artist lets the oil in her paint leach around each figure on a porous linen, creating shadows. A roughly drawn and largely empty square, a painting within the painting, is like a place of rest, an empty piazza, away from the hectic seafront.

The push and pull between the natural world and abstraction was a constant in Frankenthaler’s long career. Although she denied painting landscapes as such, many of her works bear titles suggesting location: Mediterranean Thoughts, Cape (Provincetown), Summertime in Italy, Madrid.

“I am involved in making pictures,” she told the feminist art critic Cindy Nemser and Arts Magazine in 1971. “… But often ‘nature’ associations are used as a handle held on to by people who want a clue as to how to read the surface of an abstract picture. That’s their problem.”

Problematic or not, a sense of place is very strong in a major exhibition of Frankenthaler’s work at the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence that runs until January 26 before transferring to the Guggenheim in Bilbao in April. Her relationship with Italy is – thankfully – not confined to the shortcomings of her holiday villa.

The Renaissance artist Piero della Francesca and the great Venetian colourist Titian are among her favourites, literally illuminating her path to abstraction. Her giant, exuberant works fit as to the manor born in this gracious, lofty and prestigious palace.

Frankenthaler’s privileged upbringing began in New York in 1928, where she was born, the youngest of three daughters of a judge, who died when she was 11, and his German-Jewish wife. From her home on the Upper East Side she frequented museums and galleries, and was encouraged to study art, in Vermont.

Within four years she began a five-year relationship with the influential art critic Clement Greenberg, 20 years her senior. Through him, she met the giants of contemporary art: husband and wife Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner, Elaine and Willem de Kooning, Barnett Newman and sculptor David Smith. She was soon exhibiting alongside some of these foremost names and had two been given solo exhibitions before the age of 25.

The painting that made her name, sadly not in the show but on loan to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, is Mountains and Sea (1952). This elegant experiment in paint-pouring on unprimed canvas, with its charcoal arabesques and pools of colour, baffled even some of her avant-garde friends when it went on display at an influential New York gallery, and went unsold at $100.

The art world had flocked to the vigorous gestural painting of Pollock, considered the greatest painter of his time, and of his contemporaries. Frankenthaler’s lighter hand and paler palette disarmed those tuned into more aggressive expressions of modern angst. With Greenberg behind her, she did not waver, sticking to her warm, rich colours in Open Wall (1953) and working confidently on a massive scale: this oil on canvas is more than three metres wide. Blocks of red, blue and gold are variously smooth- and rough-edged, and suggestive biomorphic figures poke through.

Further suggestive little creatures populate Western Dream (1957) and Mediterranean Thoughts (1960), whose central figures in blue seems to echo the mother and child motif that Frankenthaler would have absorbed on her many and extensive travels in Italy. One trip with Greenberg in 1954 took in Rome, Naples, Florence, Venice, Milan and the hill towns that cradle early religious treasures.

In 1957 Frankenthaler met Motherwell, an abstract expressionist noted for his intellect and political convictions. The couple married a year later.

In their 13 years together, Frankenthaler was given two landmark exhibitions – her first Italian show, in Milan and a retrospective seen at both the Whitney Modern Art Museum in New York and the Whitechapel Gallery in London. By now the artist was working not only on a huge physical scale but demonstrating a range of ideas that never stand still.

Unlike many of her contemporaries, she is not identifiable at a glance, but was capable of a vast range of effects and colour palettes, in works often inspired by place. In Madrid (1984), it is as though she visited the city’s Prado art gallery, boiled up a couple of works by Velázquez, a painter she hugely admired, and then painted with the resulting brown soup, laced with velvety crimson, jade and gold.

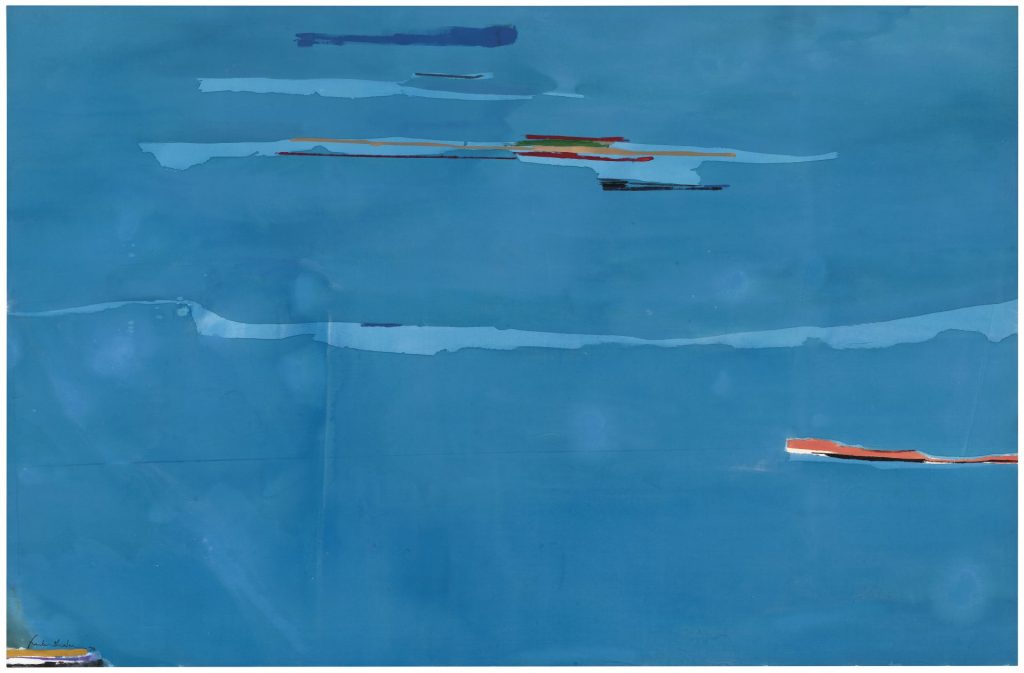

Driving East (2002), is a view that any motorist or passenger would recognise, a heavy sky pressing down on a glimpsed townscape, all the greys melting into one. Ocean Drive West #1 (1974), by contrast, is a coastline awash with idyllic marine blues.

The references may feel familiar, but the means by which they appeared were not. Video footage of Frankenthaler at work in her studio shows her stretching out at full length across the floor into the centre of the paper, canvas or linen, working in from all four sides. Sometimes she poured paint from above, in a process called soak-staining, at other times she sponged liberally, drawing rapidly with paint.

As a young woman, she had seen Pollock at work and was impressed by the muscularity of his actions – “working from the shoulder, not the wrist”. The immense physicality with which she launched into her own work was demanding. Writing only in her mid-30s, to Smith in 1963, she admitted: “The older I get the more impossible it becomes… It takes me longer and longer to get my wrist, head, soul together and then free it all at once if you know what I mean.”

Effort it may have been, but in the Sixties she hit a rich seam, telling Smith in the same letter that “I’ve been doing a lot of seascapes and landscapes, an old and frequent delight of mine”. In Cape (Provincetown) (1964), a giant twister spirals up across the green sea and sandy beach, slicing the sky with a colour chart of blues. Three years later, one of her most-loved works, The Human Edge, rejoices again in the simple impact of colour blocks, banners of grey, vibrant orange and cerise piercing a field of white above an anchoring blue.

The later paintings offer more nuanced and subtle insights into the world as she saw it. She had travelled widely over several decades, blinking into the darkness of great and ill-lit architectural masterpieces, before painting Cathedral (1982).

Here she dimly makes out perpendicular lines and the glow of precious objects as the sun breaks in to the gloom from above. The title of Star Gazing (1989) feels like wishful thinking: peering into the night sky, what look like the tops of skyscrapers float where the stars should be, and penetrating lights come not from the heavens but from the neon sign and traffic in the cityscape below.

Divorced from Motherwell in 1971, in 1994 she married the businessman Stephen DuBrul. At an age when she might have retreated into visual sobriety, like so many brilliant artists she finds in her maturity the most exuberant expressions yet, with a dazzling day in the sun, Southern Exposure, painted on paper in 2002.

Frankenthaler had always moved easily from canvas to paper, but as it became physically too demanding to work on canvas spread on the floor, she spread vast sheets of paper across sawhorses, to work at waist height, still saturating the support with colour. She never stopped absorbing the influence of other painters, and her admiration for late Monet clearly informs some of her own late work.

By the new millennium, ill health made it difficult to work at all. Three years after a major exhibition, Frankenthaler at 80: Six Decades, in New York, the artist died in Connecticut. She left a huge legacy – not only paintings and sculpture, but an example to other, younger, artists, especially women, an undisguised admiration for the Renaissance, the old masters and the pioneers of modernism alongside her own groundbreaking practices, and a cheerful philosophy.

“Any beautiful picture to me looks as though it’s just been born at once, regardless of how many hours, or weeks, or years it took to make it,” she said. “My rule is no rules, and if you have a real sense of limits, then you are free to break out of them.”

Helen Frankenthaler: Painting Without Rules is at the Palazzo Strozzi, Florence, until January 26, and at Guggenheim Museum Bilbao from April 4 to September 28