Unusually for a man of science who didn’t believe in an afterlife, Heinz Wolff was able to read his own obituary. When the distinguished psychologist Dr Heinz Wolff died in 1989, The Sun mistook the news for the death of Professor Heinz Wolff and announced the passing of “The Great Egg Race prof ”, who was the host of the “looney inventions series”.

“We have been confused before,” said the very-much-alive Professor Wolff, “but never in such a horrifying way.”

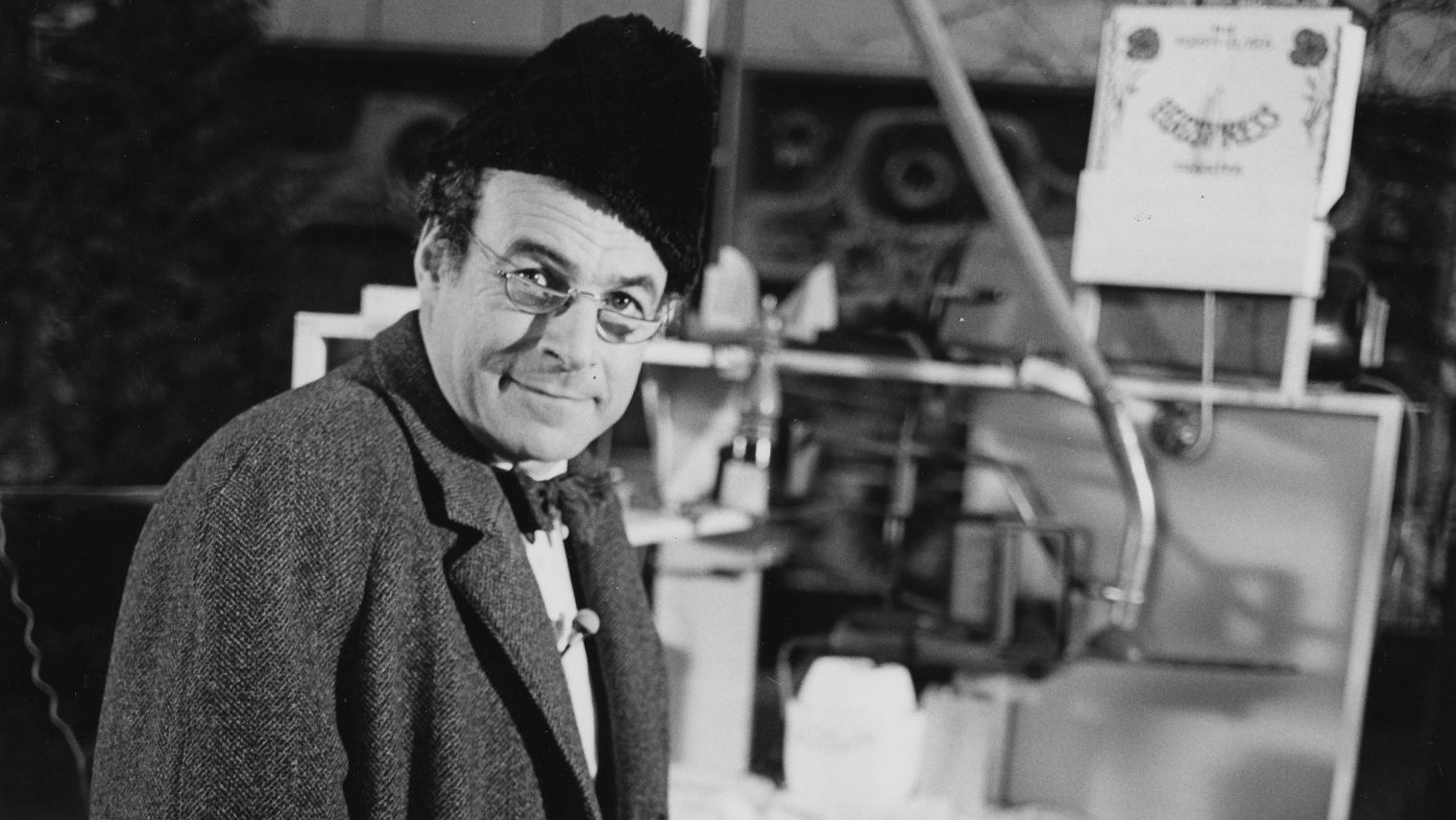

What made this premature intimation of his own mortality more remarkable was that Heinz Wolff was almost impossible to mistake for anyone else. With his bald head, wild tufts of hair protruding from just above his ears, half-moon spectacles, brightly coloured bow ties and the German accent he never lost, despite leaving his homeland at the age of 11, Wolff was the archetypal mad scientist – almost to the point of being a walking, talking caricature.

A sign close to his laboratory read Bear Right and when you did there was a stuffed bear standing there.

A favourite trick was to make a jet of flame apparently shoot out of his forefinger, once almost setting fire to the Duchess of York’s hair.

He arrived at his 80th birthday celebrations at Brunel University riding a scooter powered by two fire extinguishers. Not for nothing did he list his recreations in Who’s Who as “working, lecturing to children, dignified practical joking”.

If he played up to the image of a hare-brained professor, sometimes at the risk of harming his reputation within the academic world, it was because Wolff knew it made people listen, people who didn’t necessarily inhabit laboratories or university campuses but whose scientific curiosity could be piqued by an effective communicator.

“I even do adverts and voice-overs,” he said in the Noughties. “If, to make science and technology explainable and exciting, I have to dress up as a clown then I will do. There should be a profession of specialised scientific communicators with skills in both areas.”

Wolff was perfect for a golden age of on-screen scientist-eccentrics, such as the monocled xylophonist Patrick Moore and the ebullient, arm-flailing Magnus Pyke, and was a natural in front of the cameras from the start.

“My TV work began on Panorama with Richard Dimbleby in 1965, where I produced a radio pill that could measure pressure, temperature and acidity in the gut,” he recalled in one of his last interviews. “Richard swallowed one and when I gently poked him, the radio receiver squealed appropriately. The BBC had faith in me because I didn’t need a script and I was comfortable talking in front of a camera.”

As well as The Great Egg Race, which ran from 1979 to 1986 and pitted teams against each other in creative scientific challenges, Wolff was a mainstay of the BBC Young Scientist of the Year, appeared on children’s programmes such as Blue Peter and was an early ‘victim’ of Sacha Baron Cohen’s Ali G character, an encounter Wolff handled with characteristically warm amusement.

But there was far more to Heinz Wolff than the television eccentric: from the invention of a machine to count red blood cells, while working at his first job in the haematology department at the Radcliffe Infirmary in Oxford, to his key role in the early years of the European Space Agency. Not to mention an advisory post at the British National Space Centre that led directly to Helen Sharman becoming, in 1991, the first British person in space. Wolff ’s successes were many and wide-ranging.

He established and named the scientific discipline of bioengineering, in which scientific problems are solved through engineering practices, and, in 1983, founded the Institute for Bioengineering at Brunel University that’s now housed in the Heinz Wolff building.

By inventing the Socially Acceptable Monitoring Instrument in 1968, he pre-empted the FitBit by almost half a century, and during his career authored or co-authored 120 peer-reviewed papers published in scientific journals.

Wolff ’s passion for science was there from the start. One of his earliest memories was heating sugar in a test tube to make toffee, in his Berlin home. He was four years old.

He remembered, at the same age, “standing in our fourth-floor flat and seeing the torchlit parade of Hitler’s brownshirts”.

When the Gestapo discovered that his father Oswald, a publisher of books of German history, was advising German Jews on how to skirt around the Nazi currency laws and escape the country, the Wolffs began an itinerant existence, flitting between safe houses.

After Heinz’s mother died in 1938, the family fled to the Netherlands and applied for visas to travel to the US. When the Dutch authorities threatened to deport the family back to Germany, they rushed to Rotterdam and boarded a ship to Gravesend.

Heinz Wolff arrived in England on 3 September 1939, the day Britain declared war on Germany. He was 11 years old.

“We really cut it fine,” he said later.

They settled first in Hampstead but when the front door of their house was blown off during an air raid, decamped to Oxford, where Heinz went to school and proved to be such a gifted scientist he was offered a place at St Catherine’s College, Oxford.

Before he could take it up, the war ended and he was asked to defer for a year in favour of students returning from military service. Taking a research job at the Radcliffe Infirmary instead, Wolff never embarked on his Oxbridge studies.

When Wolff was headhunted by the National Institute for Medical Research at the age of 26, the organisation was startled to learn he had no university degree. They arranged for him to enrol at University College London, where he earned a first in physiology and physics, his previous work permitting him to cite his own publications as part of his studies. Returning to the institute after his graduation, by 1962 Wolff was head of the biomedical engineering division.

Thirty years later, he left to found the bioengineering faculty at Brunel.

In addition to his research, Wolff worked tirelessly to maintain the independence and dignity of the elderly, from devising vehicles they could enter and exit easily, to designing ‘safe’ living accommodation. When his wife Joan lay dying in hospital in 2014, after more than 60 years of marriage, Wolff invented a morphine dispenser pump to help ease her final days.

Three years later the same device was put into use for his own last moments. Over the years his natural compassion had underpinned inventions that helped human beings from deep-sea divers to astronauts.

It took until the very end, but Wolff ’s work had finally been of benefit to himself.