Sometimes it’s easy to forget that we live on an archipelago where one is never more than about 70 miles from the sea. The basic geography of these wave-lashed, wind-blasted lumps of rock we call home define us as maritime people and, whether we realise it or not, the sea affects almost everything we do, say, wear, eat, use and think.

Ninety-five per cent of all UK imports and exports arrive or depart on ships, but the influence of the sea goes much deeper than economics. It washes into our collective psyche, injecting a briny tang to the very core of our being.

The sea is a brooding presence around us, its frequent beauty and the benefits it provides masking an almost limitless potential for malevolence. The history of these islands is riddled with huge storms that have sent the sea crashing into and over the land. Every year the North Sea nibbles away at stretches of the fragile east coast of England, sending houses once safely inland tumbling on to the foreshore, spilling their contents and memories into the waves. Whole towns have been swallowed by the tides, creating legends in which the bells of lost churches still peal beneath the waves.

The shore itself presents a strange kind of hinterland that’s neither land nor sea, alternately submerged and exposed, growing and shrinking our boundaries twice daily with the tides. Often the retreating waves leave perverse gifts in this liminal place: a lobster pot from another continent, a coil of rope, a message sealed in a bottle, a stranded whale.

Sometimes the sea even leaves us a body.

There are few places around the coasts of Britain and Ireland where you will not find at least one memorial to victims of the sea; shipwrecks and tragedies that have torn the hearts out of small communities and whose legacies linger in surnames on memorials and headstones that match those of current residents.

In most coastal churchyards you will also find those who are a long way from home, washed up there by a sea utterly indifferent to their fate that can even strip them of their identity to leave them nameless in the ground. The sea bequeaths loved ones only a story without an end, a grief undefined, a guttering flame of useless hope, an infinity of unanswered questions.

The unsettling presence of the sea and the appearance of a stranger’s body on a beach underpin two new debut novels that have much in common despite being wholly different in their execution.

Both are set on the remote fringes of our islands in communities with their backs to the shore that feel like neither land nor sea, havens for the outsider and the vulnerable. Both places are disrupted by the appearance on their beaches of a body and the novels follow the resultant reverberations.

Ben Tufnell’s The North Shore opens like a classic gothic novel. The first page features an approaching storm and an approaching death and there’s a graveyard on page two. Set in a remote village on the north Norfolk coast on the fringes of the flatlands that make up the eeriest part of Britain, the reader can almost sense the solemn tolling of a funeral bell and the creak of a coffin lid from the off.

There is no bigger fan of gothic fiction than me (in fact, here’s a tip: sign up to Dracula Daily. Bram Stoker’s classic was written in the form of letters and diary entries and beginning on May 3, Dracula Daily will email you sections of the text on the dates they occur, meaning you experience Dracula effectively in real time, for free). And while the opening of The North Shore had me settling in for a spooky ride on a literary ghost train it turned out instead to be something quite different and original.

The nameless narrator is a youth sharing a cottage with his mother who, as the storm approaches, has left for the hospital where the boy’s grandfather lies dying. He’s alone in the house as the storm hits, a proper, full-on, tree-felling, tile-flinging maelstrom. When it finally subsides, the narrator sets out to inspect the damage and on the shingle beach finds among the debris “a crumpled heap of dirty dark cloth, draped in bladderwrack and tangles and haloed by dead starfish”.

It’s the body of a man. Except, despite all appearances to the contrary, he’s not dead. He coughs and vomits up seaweed before being helped back to the cottage and seated by the fire in a change of clothes that belonged to the narrator’s dead father. In the ensuing hours the apparently shipwrecked mariner, who speaks a strange language, regularly coughs up what appear to be ever-growing bundles of leaves until after a couple of days he disappears from the house. In the garden, there is now a gnarled old tree that wasn’t there before, fragments of the borrowed clothes entwined in the nearby shrubbery.

The North Shore then eschews a conventional narrative in favour of something else entirely. It becomes partly memoir, culminating in the narrator’s return to the village after many years away via a gallimaufry of letters, memories and meditations on landscape, folklore and art. From Ovid to Pinocchio and from legends of the Green Man to The Day the Earth Stood Still, this apparently whimsical flit between subjects somehow keeps its cohesion without ever losing its sense of the eerie and a wide-ranging intellectual curiosity about the supernatural.

“So much of life is dull, unexceptional,” writes Tufnell. “Isn’t it so much more interesting to believe in the possibility of ghosts and spirits, to dream that mermen and mermaids swim in the sea, that a fish might be a man, that a man or woman might become a tree, as Ovid described?”

Sheila Armstrong’s Falling Animals also begins with a body on the shore, but this one didn’t wash up in a storm.

The novel was inspired by the real-life case of a dead man found in 2009 on a beach at Rosses Point in County Sligo on the north-west coast of Ireland, who remains unidentified despite widespread media coverage. When gardaí traced the man’s movements in the days leading up to his death he became only more enigmatic, fuelling Armstrong’s imagination and bringing about this absolutely beautiful debut.

Like a pebble dropped into still water, Armstrong follows the ripples that radiate from the discovery of a body on a beach in the west of Ireland, eavesdropping briefly on a string of lives linked in some way to a dead man found sitting apparently peacefully, his jacket neatly folded next to him, all traces of his identity carefully removed.

From the local guard who’s called to the body to the pathologist to two seamen on a ship previously wrecked off the village to which the man apparently has a connection, to local residents, even to a priest in Australia, Armstrong builds a vividly drawn collection of people with their own stories riddled with issues, hopes, fears and secrets that are revealed while the dead man retains his.

Both books leave us pondering the nature of truth and memory. In Falling Animals, for example, when a bus driver who brought the man to the village contemplates his appearance at the inquest, he wonders whether “this particular story has been told so many times that it has a life of its own, and he will never regain the foothold behind his own eyes”.

Who really owns our stories once they’re told, when they interact with others, when they become no longer our own? Can we trust our own memories as accurate? When, two decades after the event, the narrator of The North Shore finds an account he wrote of his interaction with the mysterious man from the beach, he finds it very different from how he remembers it.

While Tufnell focuses on one life, Falling Animals is remarkable not only in how Armstrong constructs such a range of complete lives in relatively short chapters but how these stories of often far-flung and unconnected individuals meld into a coherent and utterly absorbing whole without having to tie up every loose narrative thread. Indeed, the strength of both books lies in how they leave questions unanswered while strewing tantalising hints throughout narratives as epic and mysterious as the sea itself.

Both writers evoke the eeriness thrumming beneath these places on the fringes where nobody passes through, where lives wash up like the debris on the beach, each a journey’s end populated by the wandering secret-carriers who are drawn to them.

Grief and loneliness ripple through both these excellent novels, ebbing and flooding on the fragile shore between memory and truth. “We are small, I thought to myself,” writes Tufnell. “We are just clinging on, fast, to a piece of exposed dirt, crumbling, at the edge of a vast void.”

“All anyone wants,” writes Armstrong, meanwhile, “is to be remembered.”

The North Shore by Ben Tufnell is published on April 27 by Fleet, price £16.99. Falling Animals by Sheila Armstrong is published by Bloomsbury on May 25, price £14.99

A EUROPEAN LIBRARY

A weekly selection of fiction and non-fiction, new and old, to build a comprehensive literary portrait of our continent

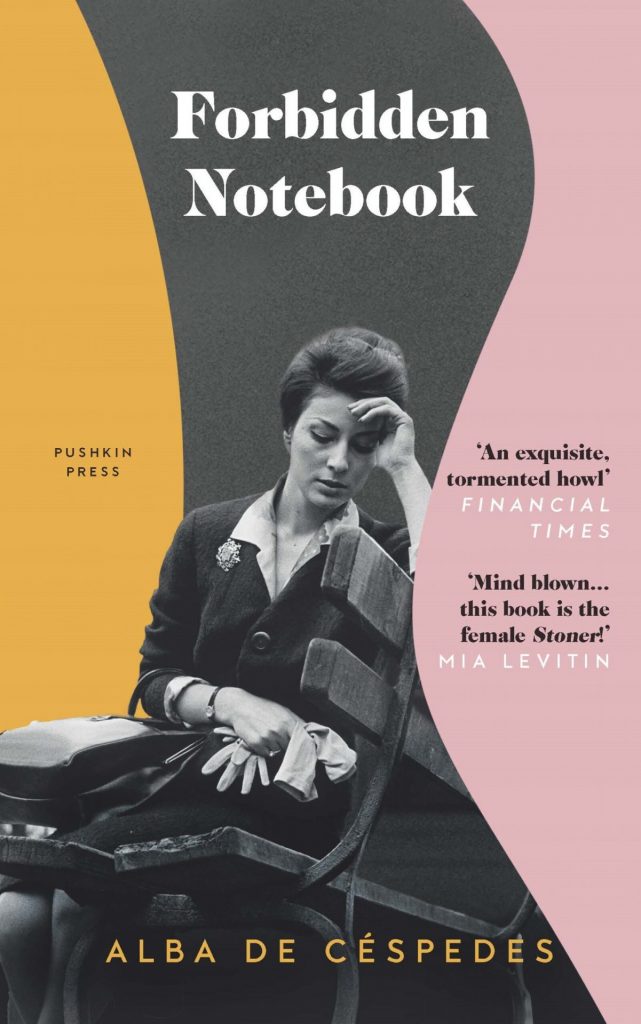

82. FORBIDDEN NOTEBOOK by Alba de Céspedes, trans. Ann Goldstein (Pushkin Press, £16.99)

Written by a remarkable figure overlooked in modern discussions of Italian literature, this is a welcome return for a 1952 feminist classic by Céspedes, who was jailed twice for antifascist activities in 1930s and 40s Italy. Written in the form of a journal by a Roman housewife, Céspedes’ creation Valeria gradually finds her voice and starts to examine her place in a patriarchal world.