Herman Edwards was a social worker in London back in the early 70s, and Brother Herman, as he was known, wanted to do something for young black Londoners, particularly those who were living on the streets. With a grant from Islington Council, he set up a house at 571 Holloway Road that took in young black Londoners who’d run out of places to go. He called the project Harambee, the Swahili word for “working together”.

It was around this time that Colin Jones, a former professional dancer turned photographer, was told by his editor at the Sunday Times to “go and find out who is doing all the muggings”. The racial attitudes of the time meant that he knew exactly what his editor was talking about. The images were meant to accompany an article by the journalist Peter Gillman, entitled “On the edge of the ghetto”.

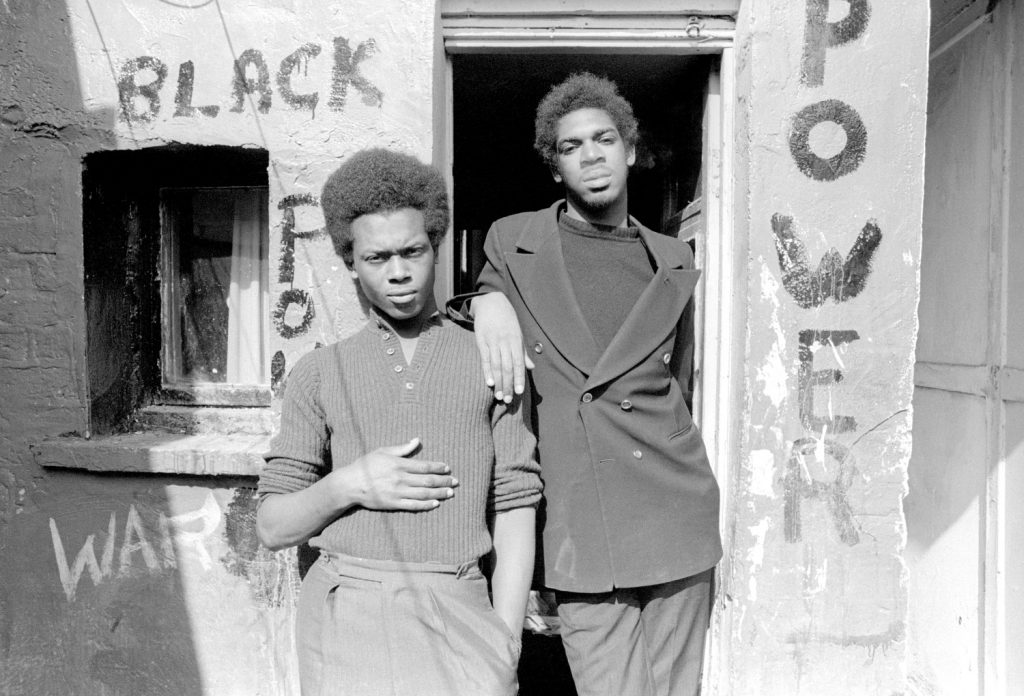

The racial politics of the time were a source of deep unease in the cities, and made worse by the activities of extreme political organisations such as the British National Party and National Front, extremist hard right parties with overtly fascist members. This prompted a corresponding increase in the activities of Black power movements.

Jones went in search of these activists but they would have nothing to do with him. Eventually he found his way north to the house on the Holloway Road, which had become known to locals as “The Black House”. That name had been given to another house in the same part of London that had been set up by a former pimp and radical activist called Michael X, who was eventually hanged in Trinidad for murder. The houses were unrelated – but the name stuck.

At first, the Harambee house’s occupants didn’t want to let Jones in. At that time, the media had developed an unhealthy, exploitative interest in the black urban experience, using fear of the inner-city youth to sell newspapers. The people at Harambee knew this very well.

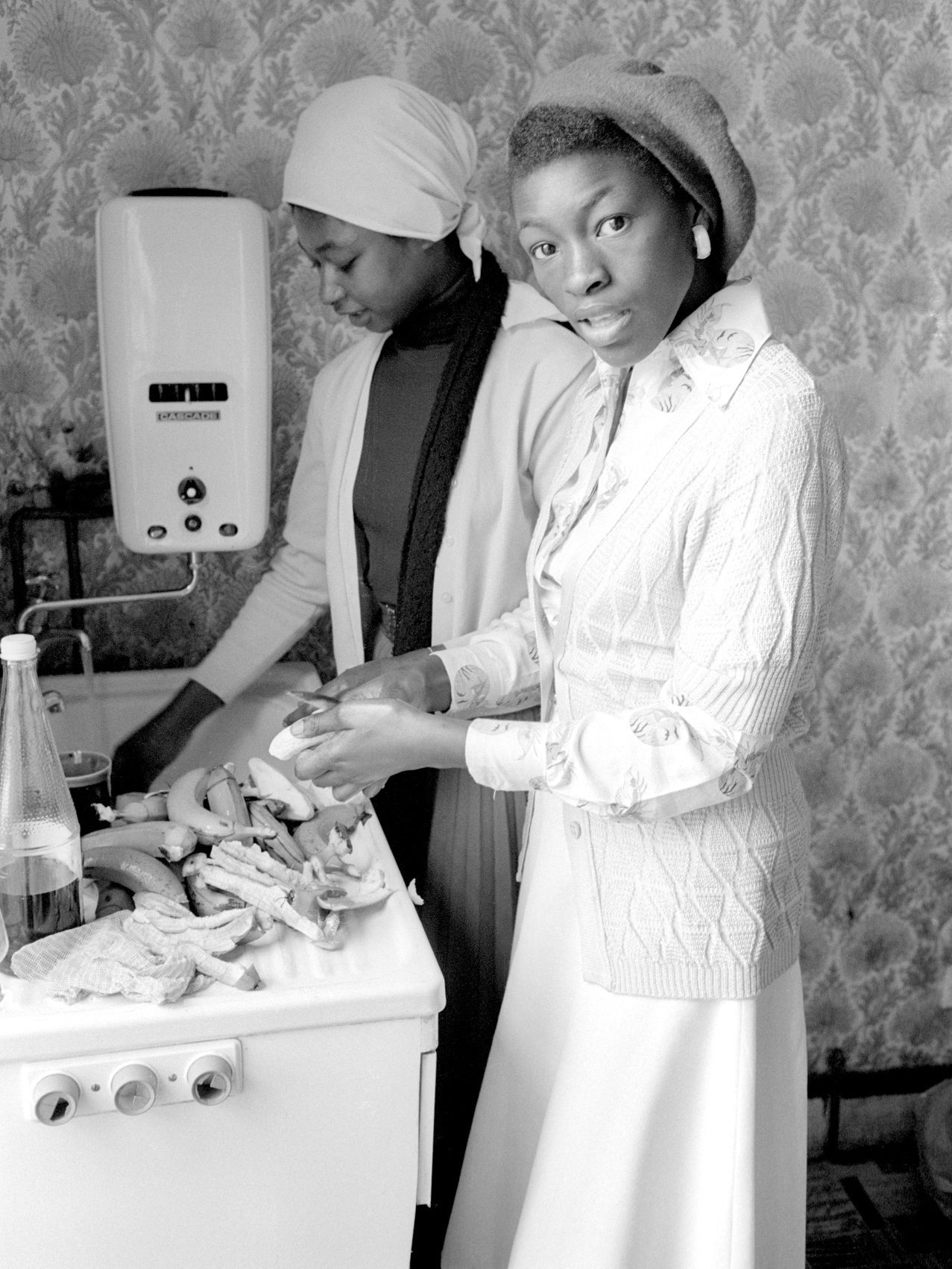

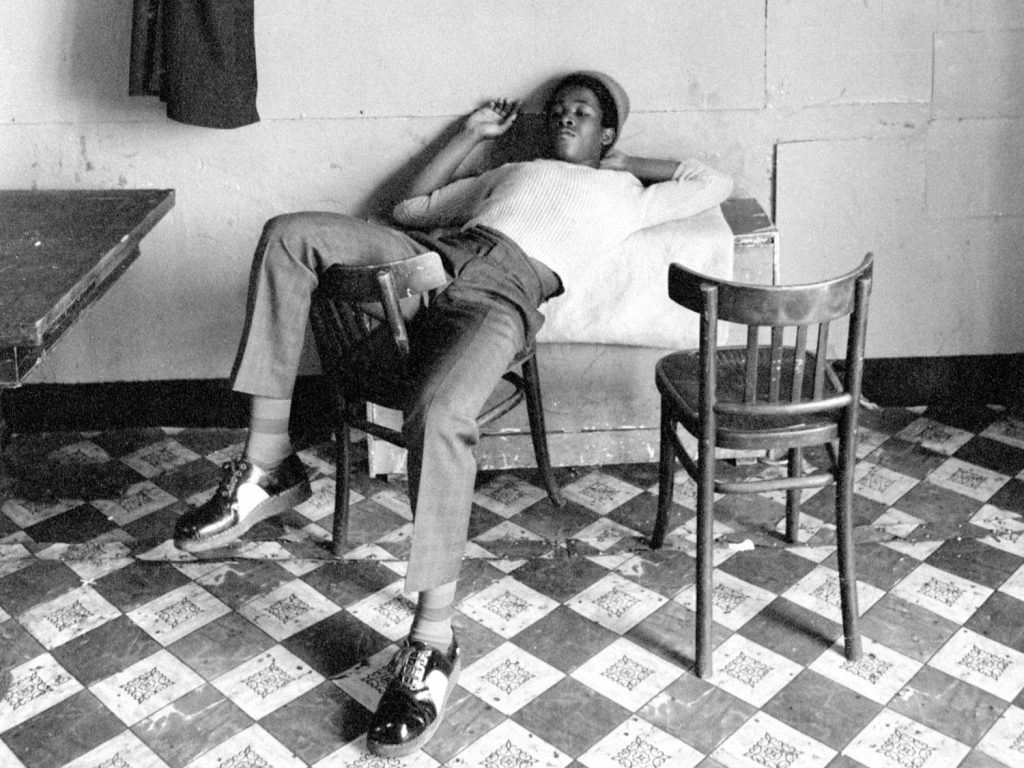

But Jones talked them round, and when he was eventually allowed inside, what he found was anything but glamorous. Most of the house’s occupants were from Caribbean families and were second-generation, torn between their aspirational first-generation parents and the brutal reality of 1970s Britain. They had no qualifications or prospects. The job market for black workers at the time was a closed book.

Jones commented in 2006 that:

“My camera in the house was very intrusive so I wasn’t always able to use it as it could have provoked some situations to turn violent. The problem is that I am white and these people, with all their problems, have very little to lose. Sometimes when I go through the front door I can feel the pressure in the place.”

The house often smelled strongly of ganja. Many of the men ended up spending time in jail. The girls who passed through the house tended to do better. In an interview with the Islington Tribune, given in 2017, Jones recalled how one of the young men he met “was in a state of depression after he blinded his father with a bottle in an argument.”

When Jones’s images first ran in the Sunday Times, they caused a storm of controversy. Many people in the black community resented the fact that he was making money out of their hardship. In 1977 the images were displayed at the Photographers’ Gallery in London in a show called The Black House. Jones was criticised again, but for glorifying people who were – at the time – widely regarded as forming part of Britain’s criminal underclass.

Jones told the Tribune: “I knew that what I was doing, for a white person to get inside that place, was a privilege… It was like you found something that was unique and you stuck to it and no other people had done it.” The house closed shortly after Jones took these photographs.