In December 1526, fresh from a boat trip crossing what was known as the “German ocean” or “British sea”, Hans Holbein the Younger arrived in England seeking work. At home in Germany, Holbein was recognised as an excellent painter of portraits and biblical narratives as well as a book illustrator and a designer, but he was little known in England. Luckily, he had with him something that would open doors: a letter of introduction addressed to Sir Thomas More.

Born into a family of successful painters, from 1515 Holbein had lived and worked in Basel, but Lutheran reforms and iconoclastic attacks on devotional images had lessened regular work for artists. The letter for More – at that time chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and arguably the most influential person at Henry VIII’s court – was written by one of Holbein’s Basel patrons, the Dutch theologian Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam.

Holbein was familiar with More’s book Utopia, for he and his elder brother, Ambrosius Holbein, had designed woodcuts for an edition published in Basel by Johannes Froben in 1518. Introducing one of the most remarkable portrait painters that Germany had ever produced, Erasmus dryly explained that work for artists had dried up in Basel. “Here the arts are shivering with cold, he [Holbein] is going to England to pick up a few angels [coins]”.

Responding to Erasmus by letter, More replied, “Your painter friend, my dear Erasmus, is a wonderful artist but I fear he will not find English soil as rich and fertile as he had hoped. But I shall do my best to make sure it is not completely barren.”

To find new patrons, Holbein had travelled through France during 1523 and 1524, visiting royal residences for commissions, without success. Yet proof of his extraordinary talent was evident. In a portrait of Erasmus, painted in 1523 and now in the National Gallery, London, the character of the sitter is revealed in an intimate, realistic portrayal, the hallmark of Holbein’s art. This painting – no doubt with Erasmus’s agreement – was inscribed in Latin on a shelf behind Erasmus’s head “I am Johannes [Hans] Holbein, whom it is easier to denigrate than to emulate.” On patrons’ portraits, Holbein liked to include a sentence extolling his artistic excellence.

It is at this point in Holbein’s career – his arrival in England – that a new exhibition – Holbein at the Tudor Court, at the Queen’s Gallery in London – begins. Within it is a visual spectacle of more than 100 works from the Royal Collection, superbly curated by Kate Heard, and set out as a chronological exploration of the painter’s work and patronage in England. On show are remarkable pieces, such as the preparatory drawing and finished portrait of William Reskimer, a page of the chamber at the Tudor Court. The preparatory drawings, paintings and miniatures, armour and silverware were all created during Holbein’s residency in London, between 1526 and 1528, and again from 1532 to 1543.

In late 1526 Sir Thomas More had welcomed Holbein to his home and commissioned him to paint his portrait, dated to 1527. It was so lifelike that More commissioned an informal portrait of his family, probably set at his home in Chelsea, created in 1527-28. Ten people, including More’s father, Sir John More, were depicted, plus servants and family dogs.

Holbein’s preparatory drawings of the family are in the exhibition. It is through the drawings even more than the finished portraits that we come face-to-face with Holbein’s clients, and the inner circle of the Tudor Court. The large painting was destroyed in a fire in 1752 and is known only through a 1593 copy by Rowland Lockey, plus a small sketch of the group layout that Holbein gave to Erasmus on his return to Basel in 1528.

Holbein’s arrival in England coincided with Henry VIII seeking an annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, in order to marry Anne Boleyn. One of Holbein’s early commissions was a portrait of William Warham, archbishop of Canterbury – a friend of Erasmus – who had officiated at the marriage of Catherine and Henry. Holbein was in the thick of it. From his experiences in Basel, he was adept at finding favour with both Protestant and Catholic patrons. He succeeded in his first two years in London through a network of Erasmus and More’s contacts.

Sir Henry Guildford, comptroller of the royal household and good friend to the king, commissioned pendant portraits of himself and his wife in 1527, after giving Holbein a commission to oversee the design and painting of temporary decorations at Greenwich, for revels to celebrate a peace accord between France and England.

Holbein, recorded as “Hans the Painter”, worked with a team of 19 others. He was paid at a much higher rate and exempt from needing membership of the English Painters and Stainers Guild due to his exceptional skills. This was his introduction to working for the royal court. It would take another nine years to become a King’s Painter to Henry VIII in 1536, on a salary of £30 per year – less than the salary paid to another King’s Painter, the Flemish artist Lucas Horenbout, resident in England from 1525 until his death.

Holbein returned to Basel in 1528, most probably to confirm his residency, because citizenship was negated after a two-year absence. He arrived home wealthy, to be reunited with his wife, Elsbeth Binzenstock, and young son, Philipp. During his near-six-year stay, three further children were born, Katharina, Jakob and Küngold. The council of Basel made generous offers for him to remain permanently in the city but he returned to London in 1532, to receive commissions from members of the Hanse, the wealthy German merchants resident in the Steelyard, a walled compound with warehouses on the banks of the Thames, close to present-day Blackfriars Station. Holbein lived close by in Mayden Lane.

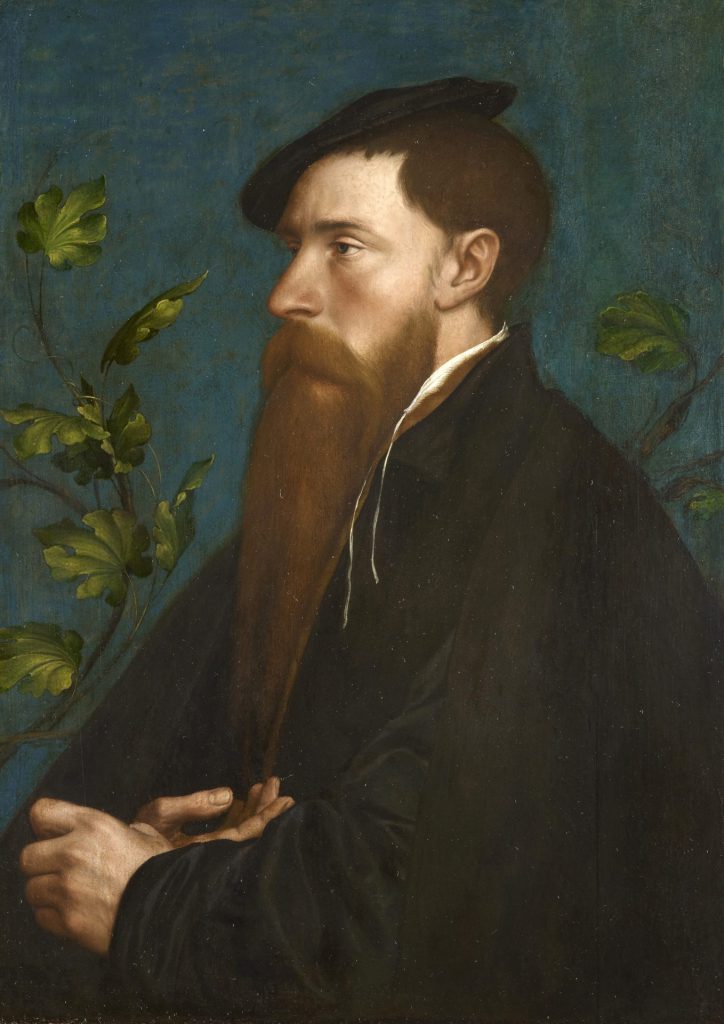

Their portraits, the first dated to July 1532, are amongst Holbein’s finest achievements. One in the Royal Collection is of a 23-year-old merchant, Derich Born, who commissioned Holbein in 1533. The flawless realism of Born’s youthful features and relaxed pose, with an elbow resting gently on a parapet, and the subtleties of clothing fabric textures are pure Holbein. Written on the parapet is a Latin inscription that includes a tribute to Holbein’s artistic brilliance: “If you added a voice this would be Derich his very self. You would be in doubt whether the painter or his father made him…”

In 1536 Holbein, now a King’s Painter, received a major commission from Henry VIII to create a life-size dynastic mural featuring the king standing with his father, Henry VII, founder of the Tudor dynasty, his mother, Elizabeth of York, and his third wife, Jane Seymour. It was a visual validation of the ruling power in Tudor England. Its creation coincided with the king breaking away from the Roman Catholic church to become head of the Church of England in 1535.

The vast wall painting was placed in Whitehall Palace where the realism of it stunned onlookers. Notably one of Holbein’s greatest works, it was destroyed in a fire in 1698 and is known today through copies, and Holbein’s preparatory life-size drawing of the king.

This majestic depiction of the king would be repeated in other portraits of him by Holbein, and copied by other artists too, to become the identifier of the English monarch across Europe. Holbein’s portraits and copies of them continue to be the most recognised image of Henry VIII nearly 500 years after the king sat for the painter.

Holbein may have returned briefly to Basel in 1538 when he travelled to European courts as the king’s envoy, to create portraits of women eligible to become Henry VIII’s fourth wife. He fell out of favour with the king after a charming three-quarter-length painting of Anne of Cleves (1515-57) did not match the real woman. The marriage between Anne and Henry lasted six months. However, Holbein continued to receive worthy commissions, and in 1541 he is recorded as a denizen – naturalised foreigner – living in the parish of St Andrew Undershaft, on Aldgate Street, in the City of London.

Two years later, on October 7, 1543, Holbein wrote a short will, asking for his horse and all his goods to be sold to pay his debts, and money assigned to provide a monthly sum for two infants “which be at nurse”. Holbein may have been suffering illness from a plague that had infected the city since May. Death must have been imminent. His executors, all foreigners living in London with whom he had worked and to whom he owed money, were the goldsmith Hans of Antwerp, Ulrich Obringer, a merchant, Anthony Snecher, an armourer, and Harry Meynart, a painter.

For such a notable artist there is no record of the date of his death, or exactly where his body was buried, or what happened to his two illegitimate children. By November 29, 1543, he was spoken of as dead after Hans of Antwerp took out letters of administration. Holbein’s will was discovered centuries later in 1861, in the archives of St Paul’s Cathedral, London. Apart from this and a few work receipts, written sources by Holbein are scarce. It is Hans Holbein’s portraits that are his legacy, revealing his remarkable achievements in England, a German influencer at the court of Henry VIII.

Holbein at the Tudor Court runs at the Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, London until April 14, 2024

Further reading: Holbein at the Tudor Court (exhibition catalogue) by Kate Heard, Royal Collection Trust, 2023; Hans Holbein: His Life and Works in 500 Images by Rosalind Ormiston, Lorenz Books, 2022