George Orwell was not much enamoured with England’s first new town. It’s not that he disapproved of the bold aspirations of Letchworth Garden City: a meeting point between town and country, a space where citizens could live, breathe and thrive. The problem was its residents.

This new community, Orwell observed, contained “every fruit juice drinker, nudist, sandal wearer, sex maniac, Quaker, ‘nature cure’ quack, pacifist and feminist in England”.

Ironically, this time around, the sandal-wearing environmentalist is the demographic most likely to object as the government pushes to develop a generation of new towns.

Those towns are needed – Britain is suffering from an acute shortage of affordable and social housing, and absurdly high prices. There are more than 150,000 homeless children growing up in unstable and often unsafe temporary accommodation. Britain’s homes are overcrowded, many suffering from disrepair leading to damp and mould. The impact on both mental and physical health is now weighing on the public purse.

For the first time in perhaps 50 years, housing was a key concern for voters in last year’s general election, and Keir Starmer’s promise to build 1.5m new homes in his first term recognised this fact. His appointment of Angela Rayner was an acknowledgement that something significant had to change in government to make that happen. It’s rare enough to see a cabinet minister who grew up in social housing; to see someone who brought their children up in social housing become deputy prime minister was a landmark for the country.

So far, so encouraging. But here’s the problem: those 1.5m homes won’t touch the sides of the crisis, and they probably won’t be built within five years.

The solution that presents itself is to build not houses but entire new towns. When Labour proposed something similar back in the late noughties they didn’t get very far; their over-complicated plans, particularly for new eco-towns, were stalled by wrangling and planning battles in Westminster. Then came the financial crisis and the austerity years. The ensuing Conservative administration let housebuilding numbers plummet and had no plans for new towns. In the end, only one of Labour’s proposed new towns went ahead. It is still not complete.

Letchworth Garden City was designed by the Victorian utopian and urban planner Ebenezer Howard. Martin Hilditch, editor of Inside Housing, grew up there, then moved to London for a while, but couldn’t stay away – he’s now moved back.

“What makes it a tremendously pleasant environment, and why it works – although also why it’s difficult to replicate – is that feeling of space,” he says. “You have all the beauty of the country and the advantages of an active and energetic town life. That’s still something that works, and that vision is still very attractive, which is why people keep trying to recreate it.”

The difference between the early garden cities like Letchworth and the later new towns of the postwar era was their size. Garden cities were designed to house around 30,000 people. Milton Keynes, perhaps the most famous of the postwar new towns, was designed for a population of 250,000 across a site of 22,000 acres.

That enormous new project was conceived as a way of taking the pressure off London, which was struggling with war damage, and in 1967 the government selected a suitable area of farmland in Buckinghamshire. The plan was spearheaded by a development corporation chaired by Lord Jock Campbell, and its design the vision of chief architect Derek Walker. The two dreamed of a modern city built with cutting-edge technology that would – if it worked – act as a model for a whole string of new towns.

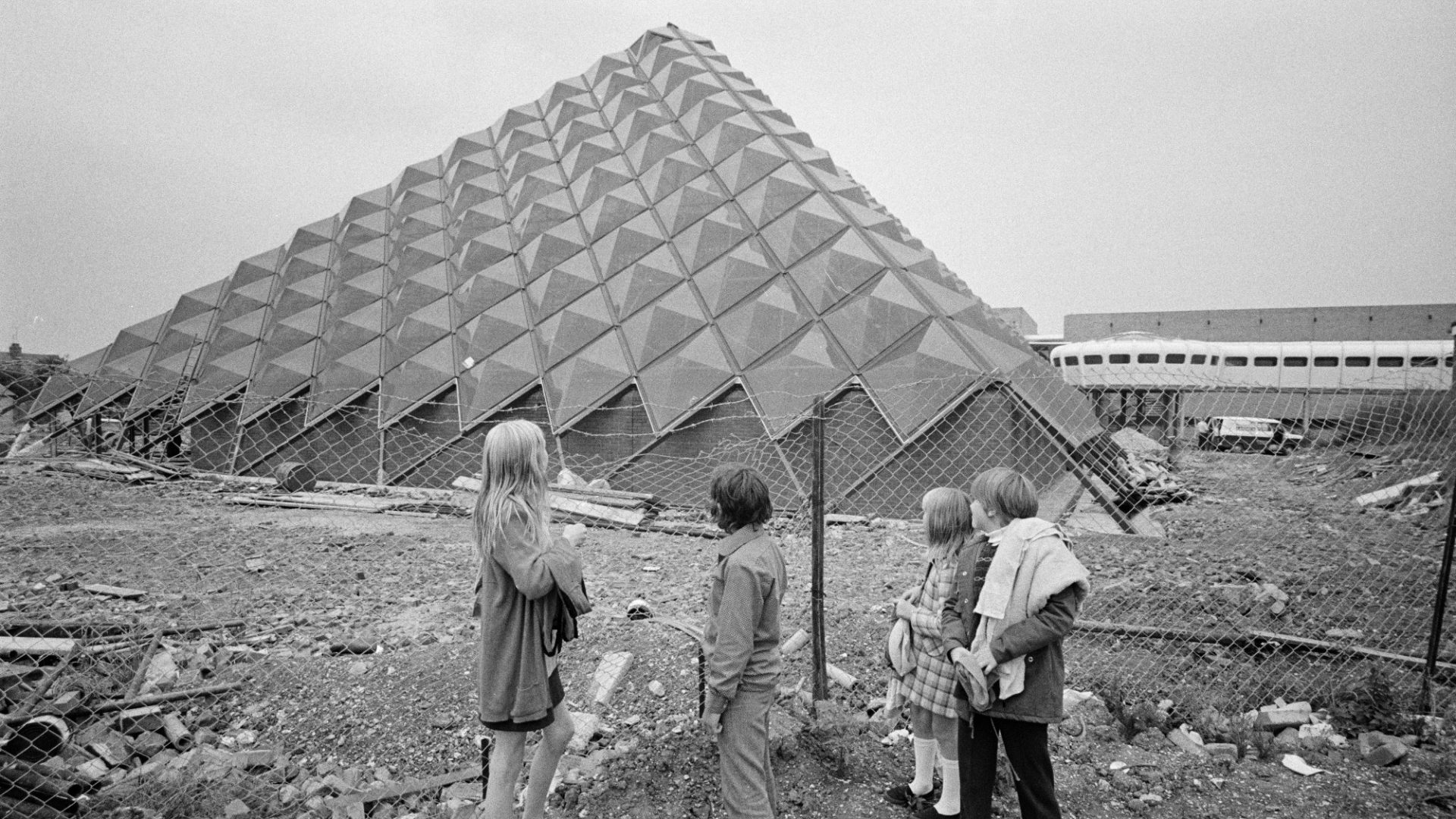

But it was controversial. To create Milton Keynes meant absorbing several historic sites, including the town of Bletchley, where residents fought hard to preserve the local identity, and small villages such as Willen, parts of which ended up at the bottom of a newly sunk lake. As well as displacement, residents also disliked the widespread use of concrete, which they considered sterile and clinical.

Building work on Milton Keynes began in the early 1970s, with its trademark grid roads, large roundabouts and visions in brutalist concrete, features that some people liked, and others found isolating and lacking in charm. Politically, the town is sometimes talked about as the zenith of Labour’s social philosophy, yet the majority of the town we see today was built under Conservative rule and involved significant private-sector involvement. That combination of social zeal and developmental entrepreneurship meant that, over Milton Keynes at least, political division ebbed away.

To avoid confrontation today, the government has appointed a new towns taskforce and most of the names in that group are familiar to me after 20 years of covering housing issues. The co-chair, Kate Barker, wrote a report on the state of housing for Tony Blair’s government in the mid 2000s, making many sensible recommendations on how to meet demand, too few of which ever came to fruition. She backed the idea of eco-towns, another good idea that never really took off.

Also in the group is Kate Henderson, chief executive of the National Housing Federation, the membership organisation for housing associations, and former head of the Town and Country Planning Association, a lobby group created by Ebenezer Howard himself.

As Hilditch puts it, she’s “an enthusiast. She knows it backwards and she’s a policy wonk”. Henderson declined to comment for this article – the whole group is keeping its cards close to its chest as it considers proposals from local authorities on 100 possible locations for new towns. The government says it will approve and begin work on “up to 12” of these developments before the next election, each with up to 100,000 new homes, along with all the necessary infrastructure. The hesitant language is a tell; Starmer and Rayner know how difficult this is going to be.

The only way to build an entire functioning new town is to do it publicly: through an independent, government-funded development corporation that designs, manages and controls the process. That corporation oversees the public funds, determines the type of housing provided and makes sure there is infrastructure to serve the new population. This makes it easier to handle the tricky job of handling local objections.

The early worry was that this Labour government did not appear to have the cojones to opt for the open approach. Then the prime minister’s first announcement on the subject confirmed that regional development corporations would lead on the creation of new towns. But that’s where the similarities end. After all, we are no longer in that postwar period when public enterprise was welcomed.

“It’s not 1945. Then, they inherited that enormous machinery of state, which was accepted and valued for its purpose, and were in a position to use that leverage in peace time,” says the historian John Boughton, whose book Municipal Dreams examines the history of social housing.

“Now, for all its rhetoric about social housing, we are still in thrall to this notion of, at best, public-private partnership, and above that the power of the market,” says Boughton. “This reflects a timorousness among Labour politicians. I would place myself as a centrist, but even in those terms we need to be braver and more positive about the positive role of the state. We have lost the notion of public investment.”

Boughton’s scepticism is well placed. The government has already confirmed that the regional development bodies will simply have an injection of public funding to buy the land required, but that this would then be returned after the sites had been sold on to private developers. That statement alone raises far more questions than it answers.

It’s not just a matter of whether it’s possible to build a series of new towns, but whether the population will tolerate it. Housing crisis or not, construction on the scale required to build a new town would face angry objections. And it may not be the most environmentally beneficial project, meaning that opposition will come from both left and right.

“Relatively low-density building in greenfield sites is probably not the best proposition,” Boughton says. The first generation of new towns and garden cities involved replacing inner-city slums with salubrious suburbs. “But if we look at Britain and compare it to continental Europe, we have very low housing density, and in this context I don’t think we should be perpetuating lower density.”

That suggests that a better, less antagonistic place to build new communities might be on the existing suburban fringes, using brownfield and “grey belt” sites, linked to transport systems that already exist. Forget the romance, and think practically.

Building on the edges of suburbia and in the inner cities is the more environmentally sustainable route and would meet far less opposition. The first official statement on new towns has proposed projects in Bedfordshire, Cambridgeshire, the east of England and the north-west.

In the south, these schemes will come up hard against the Green and Liberal Democrat nimby votes – those sandal-wearers who flocked to Letchwork a century ago. In the north, Reform is likely to link any new housing to the issue of immigration.

And even for the most ardent pro-housing campaigners, such as the Town and Country Planning Association’s policy lead, Hugh Ellis, these are important concerns. “I am a really pro-housing person who cares about my local environment. The government is trying to sustain itself on the yimby [yes in my backyard] movement, but that is very transitory,” he says. “What you can’t do is just tell people that they are evil and unthinking because they care about their local environment.”

With the government’s hyper-focus on economic growth, insistence on the involvement of private developers, and a surging Reform party snapping at Starmer’s heels, the risk is that the ideals and ambitions of the original new towns – “places where people and their experience and wellbeing were the starting point and you constructed an economic model to deliver that” – are jettisoned altogether.

If I were on the taskforce, here’s what I would recommend.

First, build these towns where they’re really needed to promote growth for the whole of England: outside the south-east. That doesn’t fit with the government’s plans for infrastructure growth, nor the statements it has made. But these towns are supposed to be social and economic engines in their own right.

Second, throw more money at it. That cash should be put in via dedicated development corporations for each new town that can plan, build and – in the longer term – manage these new places. It’s the century-old custodianship arrangement that is responsible for the success of Letchworth Garden City; why can’t we recreate that today? What good evidence is there that the private sector can really help do the job?

Finally, let those experts take the lead. There will be a backlash, larger than the anti-road protests of the 1990s. But Britain is in a period of flux. We need bold, challenging ideas. Only these will take us forward.

Hannah Fearn is a freelance journalist and podcaster specialising in social affairs. In 2024 she was named housing journalist of the year by the International Building Press (IBP)