I can’t actually remember much of what he said. If I’m pushed to recall that hazy June afternoon in 1996, my memory is of the intense heat. It was the first scorching day of the year when my all-girls comprehensive school in Didcot, South Oxfordshire was visited by a politician. The main themes of the speech he gave, I now know from later research, were the benefits of streaming in schools, and of creating a meritocratic society. I was then still a fortnight away from my 14th birthday, so forgive me that the detail didn’t stick. But one detail does stick: his name. Tony Blair.

What I also remember was the sense that the teachers, the sixth-form students, and even the handful of us who were younger, plucked to be in that room by teachers who spotted our interest in politics, were sitting at the cusp of a great change. You could debate endlessly whether Blair ever achieved the meritocracy he wanted while in government. What his visit did demonstrate, however, was an astute eye for what Didcot was coming to represent: the average British voter.

Didcot in the 1990s was a strange, slightly bleak place: “the Gdansk of Oxfordshire”, as Stephen Fry once quipped. The heart of the town was just row after row of early to mid-century council housing, much now privately owned, flanked by a thread of old railway cottages; its artery a weird one-sided high street running up the middle. It was dishevelled but boring, not disintegrating. Teenagers like me threaded in and out of a line of the British identikit shops of the time – Boots, John Menzies, Rymans – or hung around the train station, the escape route.

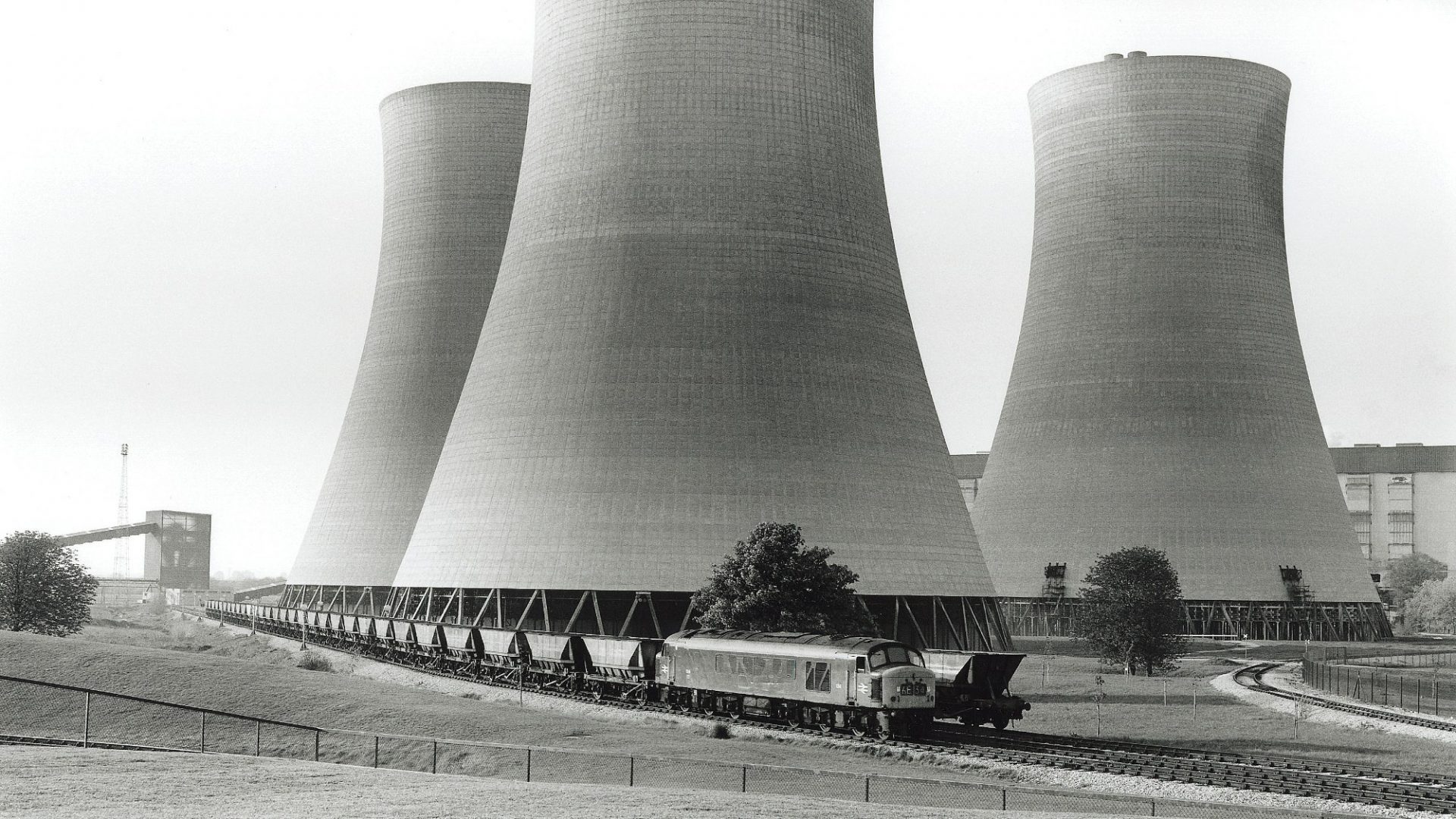

Our school playing fields sat in the shadow of the cooling towers of Didcot B power station. One afternoon, as we stumbled through a lacklustre game of hockey, a dump of strange ash rained down on us. The BSE crisis was in full swing back then, and the corpses of discarded cows were being incinerated at the site. What we probably experienced was the remnants of a garden bonfire, but the anecdote passed into legend anyway.

Throughout the 1990s I commuted into school from a nearby village, taking a 15-minute train ride in and out of town every day. I spent endless idle hours at Didcot Parkway station waiting for delayed trains (no smartphones to distract us then), staring up or down the track, gazing wistfully towards London or Oxford. The sense was always that interesting things were happening, and very close by – yet always tantalisingly, frustratingly out of reach.

At the time Didcot was a town of fewer than 20,000 inhabitants (albeit growing rapidly), with much of the population employed in local industries: the power station, the military, chemical and tobacco plants at the local industrial park, and of course the railway. Back then it was a Tory heartland. Even when Blair romped into Downing Street with a landslide, there weren’t many Labour posters on the streets here. But Didcot was changing rapidly, expanding faster than almost any other English town.

Like most of Britain in the mid-1990s, Didcot was on the precipice of something new. A large new estate on the northern edge of town tripled in size in just a handful of years, with a plan to double the town’s entire population by the 2020s. Families were moving in, and increasing numbers of people were commuting to knowledge-intensive jobs in Oxford, Reading and London, bringing new wealth to the town. In nearby Harwell, a high-tech lab provided highly skilled new work. As I was leaving, as the century turned, the profile of Didcot – and its inhabitants – was changing fundamentally.

In the 1947 James Stewart film Magic Town, a pollster finds an American town that he thinks is the most ordinary place in the country and which therefore gives the most accurate picture of national opinion. Eight years ago, a British pollster inspired by the movie carried out a similar exercise using data from the Office for National Statistics to find Britain’s “Magic Town”. It was Didcot.

According to that study, by ASI Data Science, my old home town was a remarkably close match in terms of the average British lifestyle, average opinion and experience. In 1996, Blair had realised that the normal British voter was changing. It would take a longer time for this change to register in local voting habits, but the shift was under way – and it was long term.

My family no longer lives in Oxfordshire, but over the decades I have gone back to visit friends. Each time it’s like visiting a new place: the Didcot of my memory no longer exists. If I drive I can get lost, because the road layout is so different. The old high street is no longer the centre of town; a major new shopping and entertainment centre has replaced it, running straight up from the busy railway station and entirely covering what was once a large patch of scrub that was used as an overflow car park. It now serves a population of approximately 35,000.

My old school has gone on a journey from being average but well regarded, to requiring rapid improvement, to one of the top comprehensive schools in the country. There is more money around, even in these tricky economic times – but though on paper it is a wealthier place, the extremes between the richest and poorest areas are now even more acute.

As well as an influx of people trying to escape the extreme housing costs of London and elsewhere, there has also been significant immigration from EU nations, including a growing Polish community. When the 2024 general election was called and I saw that a well-known local businessman had announced his candidacy for Reform, I held my breath. On Facebook and among my wider circle of friends, I had become aware of right wing conspiracy theories that were beginning to spread, particularly around the coronavirus pandemic.

But how times have changed. Back in 2019, in preparation for adjustments to constituency boundaries, a projection for the new Didcot and Wantage seat predicted a 10,000 Tory majority. Last summer, that seat – plus three other neighbouring constituencies that Blair never won – turned Liberal Democrat. The demographic change has been huge. Of the 20,000 adults aged over 16 who are employed in the constituency, more than half were registered in the top three professional groups: managers, directors and senior officials; professional occupations; and associate professional and technical occupations.

Ed Dorrell, a researcher at Public First who carries out focus group sessions assessing changing public opinion, says we’re witnessing “a hardening of the liberal base” in commuter areas such as Didcot, which are now heavily populated by knowledge workers pushed out of cities by the high cost of housing. “You have this influx of graduate workers with young families and they carry none of the political influences of the places they’re settling down in. They represent a completely new political position, and it creates a liberal metropolitan versus conservative post-industrial divide,” he says. “They build the kind of community they want, and they exist in their own bubble in exactly the same way they would have done in London or Oxford.”

These constituencies ought to be a future battleground for the heart of conservatism – and there are certainly signs that the Lib Dems realise they must hold on in order to consolidate their position. But these shifts create a serious predicament for the Tory Party. Kemi Badenoch’s focus on supporting farmers over land inheritance tax suggests she has one eye on this problem, but the vote she’s chasing in the former Oxfordshire strongholds is no longer primarily rural or semi-industrial.

Other towns ranked as representing “normal” voters in the original Magic Town study included Droitwich Spa in Worcestershire and Southwick in West Sussex. Both have undergone similar shifts, resulting in radically reduced Tory majorities, to Labour’s gain.

Dorrell says of the Conservatives that “their route to power is really hard to plot. Do they pivot to the right, or to the centre where the Lib Dems are resurgent? Do they think they can win on a ‘small c’ conservative MAGA-light platform in somewhere like Middlesbrough, dividing Reform and Labour? But then if they do, can they win back Oxfordshire seats that have swung Lib Dem as far more than a protest vote? That’s really hard.”

In their attempts to hold on, there are signs that the Liberal Democrats are making a similar mistake of appealing to a declining vote share. Rapid development has caused social tensions among Didcot’s original population.

New Lib Dem MP Olly Glover (himself a former railwayman) told me that he is focusing on infrastructure, including new GP surgeries and a campaign for a new railway station in the nearby village of Grove, connecting a relatively isolated part of the constituency directly to Oxford.

But nationally, the story is a different one. Nimbyism has come to characterise the Lib Dems’ positioning on housebuilding and planning – historically it was a surefire strategy to shore up rural votes, but what if that vote has now vanished?

Dorrell says that the Labour government is trying to occupy a “Johnsonian” position, in an attempt to prevent a wave of support for Reform in the north. Being tough on immigration, tough on benefits, and moving money from aid to defence will alienate potential voters in these newly forming liberal communities. “We’re moving into a position where you can see big chunks of the country where the battle will be Green versus Liberal Democrat.”

In its new upwardly mobile form, Didcot and Wantage is also a constituency lost to the Conservatives for good. Just like the Britpop years of teenage memory, that moment has passed. It is not coming back.

Hannah Fearn is a freelance social affairs journalist and writer