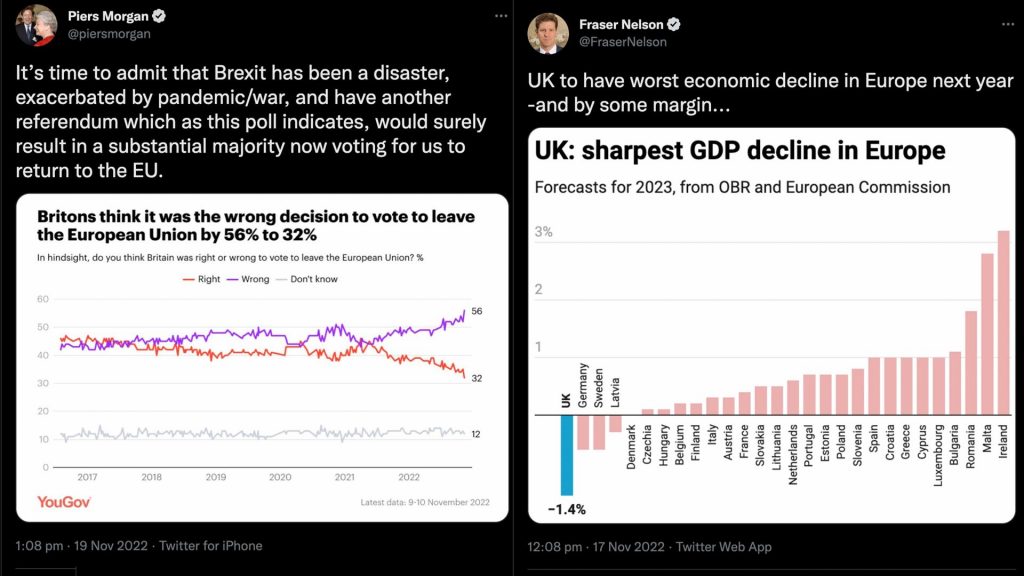

Have we reached a “tipping point” over Brexit? The UK’s economy is hobbled, Paris has overtaken London as Europe’s largest stock market and every week seems to bring worse and worse news for Brexit believers, be it from polls that indicate that the decision taken in June 2016 is now widely viewed as a mistake, to the struggles of Brexit-backing business people (Next’s Lord Wolfson, demanding more foreign workers) or regions (a huge fish processing factory in Grimsby has closed, with its bosses partly blaming you-know-what).

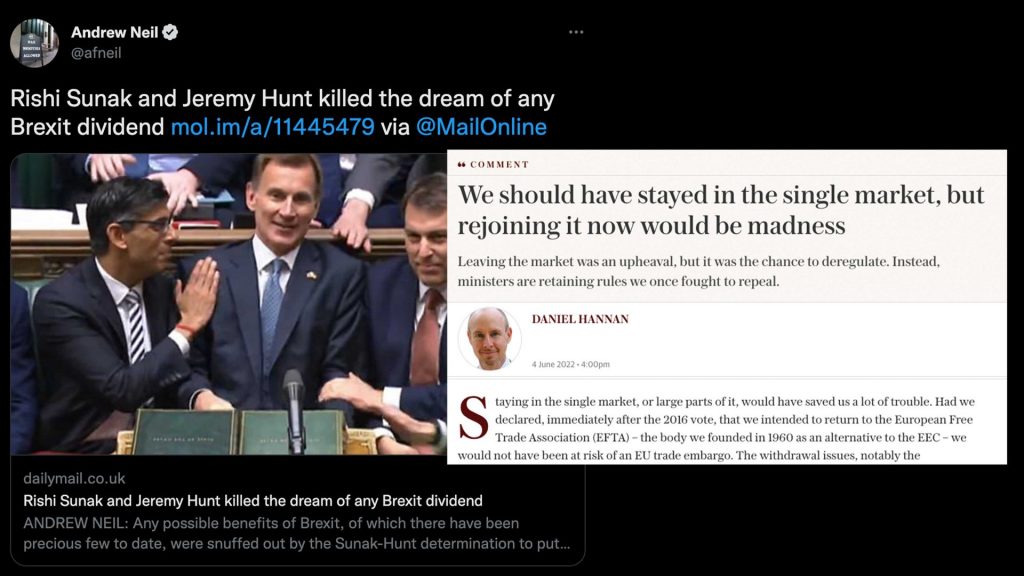

Even those once aboard the ship are abandoning it: Andrew Neil has told Mail readers that Jeremy Hunt’s autumn statement marked “The week that Brexit died” and the Telegraph has gone from “vote Leave to unlock a world of opportunity” to “we’re in this mess because of Brexit”. In the past few days, a former cabinet minister has admitted that the much-heralded Brexit free trade deal with Australia is hopeless and the government has floated – and retracted – the idea of a Swiss-style deal with the hope of reducing trade barriers.

To cap it all, the Office for Budget Responsibility now predicts that next year Britain will be the sick man of Europe once again, with the sharpest economic decline in the continent. As Piers Morgan – who vehemently opposed calls for a People’s Vote – commented on Twitter, “It’s time to admit that Brexit has been a disaster”.

YouGov’s tracking question – were we right or wrong to leave the EU? – suggests there is broad agreement with that view. For the past 12 months those saying “wrong” have comfortably outnumbered those saying “right”. The latest figures report the biggest gap yet, 56% to 32%. One in five of those who voted Leave six years ago – more than 3 million people – say we took the wrong decision.

There has been a shift in favour of rejoining the EU; however, different polling companies produce different figures. BMG sees a narrow 52-48% division – the precise opposite of the 2016 result – while Omnisis and Deltapoll report figures around 58-42%. YouGov comes in the middle of this range. But now, has something changed? Have we reached a tipping point in public opinion on Brexit? And if we had, would it even be possible to tell?

Let us start with a curious thing about the week Queen Elizabeth died, for it has lessons for the current state of British politics. The curious thing is what didn’t happen. For years, polls had found that only one person in three wanted Charles to succeed his mother. Yet when the day came, the other two-thirds failed to register their objection. Did all those polls mislead us about our hostility to Charles?

In one sense no, in another sense yes. No, because they asked perfectly valid questions. Yes, because they did not distinguish between shallow attitudes bordering on indifference, and intense determination to break with tradition. In this case, the first sentiment was far greater than the second.

This is a glaring example of a wider challenge in interpreting opinion polls that suggest changing views. Which views are firmly held and which bend with the wind? And when numbers change, do they reflect a crucial tipping point in the national mood or a brief wobble of little significance?

Eighty years of polling tell us that shallow views and short-term fluctuations have often been the norm. But from time to time there has been a tipping point, when attitudes harden decisively towards the government of the day (and, occasionally, the opposition). Has this happened this autumn? And what should we read into the rise in opposition to Brexit? Here are the clues from history.

The first tipping point reported by the polls came during the second world war. Gallup consistently found a big appetite for radical social reform. As well as asking people about specific policies, it started measuring voting intention in May 1943. For the next two years, it found Labour well ahead. In those days, polls passed unnoticed. Even when Gallop accurately predicted a clear Labour victory at the end of the 1945 election campaign, it failed to disturb the prevailing consensus that Winston Churchill’s Conservatives would win.

In the spring of 1963 came another tipping point. Labour’s new leader, Harold Wilson, presented himself as a modern, youthful alternative to an ageing prime minister, Harold Macmillan, at the head of an out-oftouch and discredited elite. One of the most glorious scandals amplified the contrast when John Profumo, the war minister, first denied and then admitted sharing a girlfriend with Russia’s naval attaché. Labour moved into its highest lead since 1945, and although the gap narrowed the following year, Labour ended 13 years of Tory government in October 1964.

Three years later came the tipping point that ensured Labour’s defeat at the subsequent election. In 1967, the pound was under pressure. The decision to devalue it wrecked Labour’s reputation for economic competence. It limped on until its defeat in 1970.

The next period of Labour government ended in 1979 when James Callaghan, the outgoing prime minister, confided to an aide that he was destined to lose to Margaret Thatcher. Labour was suffering from “a sea-change in politics. It then does not matter what you say or do”. That sea-change was amplified by a wave of public sector strikes in the “winter of discontent”. These enhanced a growing belief that the government had become too big and too wasteful. The election paved the way for a decade of radical right wing changes.

In 1992 Thatcher’s successor, John Major, felt the full force of one of the most dramatic tipping points – Black Wednesday. Under acute pressure on the pound, Britain withdrew from the EU’s currency club, the exchange rate mechanism. Within weeks, sterling had lost more than one-fifth of its value against the dollar. The Conservatives lost their greatest electoral asset – the widespread belief that they could be trusted to keep the economy on an even keel. In 1994, Tony Blair’s arrival as Labour’s leader added to the Tories’ woes. A Labour landslide was inevitable.

Or was it? In 1997, when the Tories collapsed to their worst defeat since 1906, they had presided over four post-blackWednesday years of rising living standards, low inflation, cheaper mortgages, income tax cuts and falling unemployment. Benign economic conditions could not undo the collapse of the Tories’ reputation for competence.

As for Labour’s fate following the 2007-8 financial crash, once again the government’s reputation was battered beyond repair. The economy was on the road to recovery by 2010, but Gordon Brown didn’t get the credit.

As well as those tipping points, there have been big political changes that were the product of short-term influences and close public votes, rather than sea-changes in attitudes. Changes of government in 1951 and 1974 fall into this category, as does the Brexit referendum six years ago. Fears about immigration had been bubbling up for years, but the narrow majority for leaving the EU was the result of internal Conservative politics, the election of Jeremy Corbyn as Labour leader, and a Leave campaign that ran rings round the Remain camp. Had any of these things been different, we might still be in the EU today.

What lessons can we learn from all this about the prospects for the next general election – and Britain’s future relationship with the EU?

First, and most importantly, economic competence is the issue that recurs most, and in a specific way that is common to the defeats of Labour in 1970 and 2010, and the Tories in 1997. In all three cases, a reputation for competence was plainly undone by specific events. But, and this is surely relevant to today, all three governments actually did rather well in the aftermath of those events, but gained little credit for it. As with former chancellors – Roy Jenkins in the late 1960s, Kenneth Clarke in the mid-1990s and Alistair Darling in the run-up to 2010 – Jeremy Hunt may have to settle for the verdict of later historians that is kinder than that of contemporary voters, even if living standards start to recover by the next election. When a reputation for competence is gone, it’s gone.

Another feature from past tipping points reinforces that message. It is commonly said that we live in a quasi-presidential democracy, in which leaders matter more than parties. If this were so, the Tories might have grounds for hope, because Rishi Sunak’s reputation is far higher than his party’s.

While Labour outscores the Tories comfortably on virtually every measure of party reputation, polls show a much closer contest when voters are asked about the personal qualities of Sunak and Keir Starmer.

However, had leaders’ ratings decided elections, Clement Attlee would not have become prime minister in 1945, nor Thatcher in 1979. When views of parties and leaders diverge, it’s the reputation of the party that, historically, has mattered more. We can probably add the Tories’ woes in the early 60s and Labour’s in the early 80s. In both cases, the ratings of the parties and their leaders declined together, but the driving force was a party that was seen to have lost its way.

So: unless the Conservatives now defy the sustained lessons from history, they are heading for defeat at the next election.

When it comes to pinning down public opinion on Brexit, the problem is not just that the numbers vary, but that there is no referendum on the horizon. There is without question mounting public disenchantment with the way Brexit has worked out. But would the numbers stay the same if a referendum were actually in prospect? And, if one did take place, what impact would the campaign and the arguments it generated have on the way people finally chose to vote? Might the opposition to Brexit melt away, like the opposition to Charles becoming King?

If our crystal ball is cloudy, one certainty stands out: there is a mismatch between the demand and supply sides of our political market – what voters want and what the main parties offer. Even if we are cautious about the size of the anti-Brexit majority, there is clearly a large public appetite for a major reset in relations with the EU. This is confirmed by more detailed research, such as that commissioned by the Tony Blair Institute.

Given that this issue is central to our country’s future, this political market failure matters. After all, most economists maintain that Brexit has deepened our current economic crisis (in ways Jonty Bloom sets out in these pages week after week). To be sure, in our current economic climate, voters are more concerned with more immediate matters. But the caution of the Liberal Democrats and Greens, as well as Labour, seems odd, not least because of the links between Brexit and austerity, which they could assert with far greater force.

Have we reached an electorally decisive tipping point on Brexit? I’m not sure. Could effective campaigning achieve one? Definitely