It was difficult to be controversial in fin-de-siecle Vienna. It wasn’t quite a case of “anything goes” in the Austrian capital during the 1890s, but there was an almost permanent whiff of pheromones in the air around the Ringstrasse as the city air crackled with sexual tension, intrigue and release.

The fields of art, music, nightlife and even psychoanalysis thrummed with the erotic: Arthur Schnitzler’s plays pushed boundaries, Sigmund Freud placed the blame for a pervasive social anxiety at the feet of sexual repression and a refusal to submit to desire. Even some of Gustav Mahler’s lush orchestration seemed to have a sense of intimate indulgence that was practically sexual.

It would take something pretty special to outrage Viennese morals in the

sunset years of the 19th century. But Gustav Klimt managed it.

Commissioned in 1894 to produce three paintings on the themes of philosophy, medicine and jurisprudence to decorate the ceiling of the Great Hall at the University of Vienna, Klimt battered through the traditional realm

of allegory into a world of overt sexuality and thrumming eroticism.

The paintings never graced the ceiling of the hall. When they were exhibited

there were complaints from no fewer than 87 members of the university, who raised a petition calling for the Ministry of Education to cancel the commission.

They were, they weren’t afraid to admit, as baffled by what Klimt had produced as they were outraged by the graphic sexuality of the works. Medicine, for example, featured a tower of writhing naked bodies from which a skeleton grinned in the centre, a work the university’s Catholic faction went as far as calling “pornographic”. When they saw Klimt’s interpretation of Philosophy, the science faculty complained that instead of celebrating the debate and discussion of themes of great import, Klimt’s work was instead openly assaulting “the ideas of reality and facts” with naked people. Not naked people perfectly rendered in the manner of Greek and Roman statuary, either. These were naked people depicted as, well, regular naked people.

While the Department of Education didn’t cancel the commission, Klimt’s

work went not to the university but to the State Gallery of Modern Art instead, before eventually being among a number of Klimt’s creations destroyed by the Nazis at the tail end of the Second World War. Subsequently, his 1899 Nuda Veritas also caused a stir with its full-frontal depiction of a nude woman with long red hair beneath a quote from Schiller that translates as, “If you cannot please everyone with your deeds and your art, please a few. To please many is bad”, as close to the overt expression of a personal artistic manifesto as Klimt ever got. This is who I am, he appeared to be saying, take it or leave it.

Yet until the mid-1890s, Klimt had given no hint that he was an artist capable of shocking the laissez-faire populace of his native city.

The son of a goldsmith, Gustav Klimt was born into intense poverty in a poor part of Vienna, but managed to secure a scholarship at the Viennese Kunstgewerbeschule, the school of applied arts, at the age of 14 to study architectural painting. He immersed himself in a conservative education that developed a conservative style where Titian, Peter Paul Rubens and Velázquez were key influences, along with the Viennese historical painter Hans Makart, none of them particularly renowned as fermenters of modernist artistic revolution.

On graduating, with his brother Ernst and a friend, Franz Matsch, he founded Klimt, Matsch & Co, a company of artists who won commissions to paint murals and ceilings inside public buildings.

Their work could be seen at the Burgtheater and Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, as well as commissions further afield in Romania and Bohemia. A steady, respectable but unspectacular career beckoned until the 1890s, when Klimt began to seek more from his work than formulaic municipal mural commissions.

The death of Ernst and his father within a few months of each other in

1892 possibly contributed to Klimt’s subsequent flowering as an artist of

immense gifts and imagination who slipped from the shackles of conformity while still harnessing its techniques.

The university commission coincided with the opening of a schism in Viennese art between the traditionalists, centred on the Künstlerhaus, the prestigious association of artists of which Klimt was a member, and those seeking to explore more experimental artistic directions.

Frustrated that the conservative Künstlerhaus had a virtual monopoly on exhibition space, in 1897 Klimt, fellow artists, and figures such as the designer and architect Josef Hoffmann quit the Künstlerhaus and founded the Vienna Secession, with Klimt appointed its president.

Its aims included the provision of outlets for non-traditional artists, to stage exhibitions of significant foreign artists such as the French impressionists – which the Künstlerhaus had refused to countenance – and to establish a periodical, Ver Sacrum.

The establishment of the Secession also coincided with the start of Klimt’s “golden” period. Inspired by the Byzantine interiors of the cathedral at Ravenna and a visit to Venice, and possibly a nod to the trade of his late father, Klimt produced a series of paintings exquisitely collaged in gold, usually of society women.

Ninety-nine years after it was completed, in 2006 Klimt’s lavishly golden Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I sold at auction for £100million, at the time a record for a painting.

The same year a second portrait without a golden theme, 1912’s Adele

Bloch-Bauer II, was bought by Oprah Winfrey for £66million and later sold to

a Chinese collector for a price in the region of £112million. Klimt’s art nouveau-influenced work became, and remains, among the most valuable art in the world.

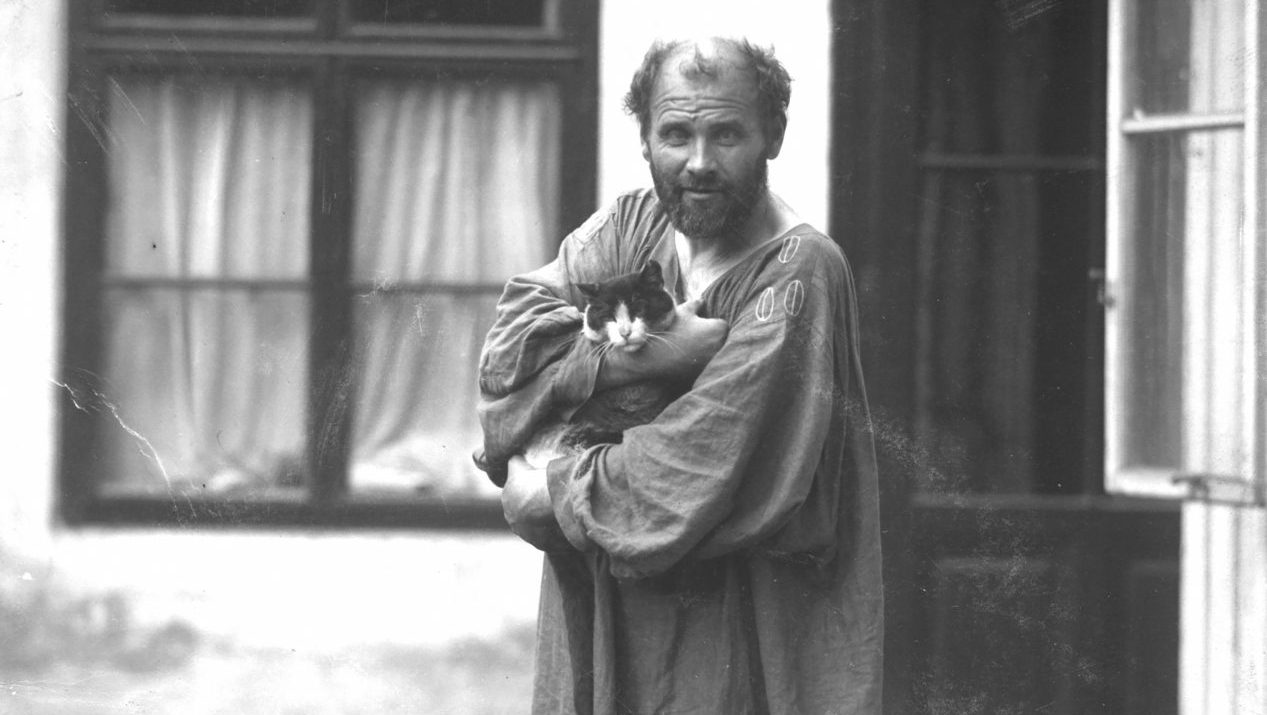

Yet Klimt lived simply and eschewed the artistic social scene based around the Ringstrasse’s opulent cafes. He spent most of his time at his studio and never owned his own home, living with his mother and sisters for the whole of his life. He wore a simple smock, his personal hygiene was questionable and his studio was often overrun with cats, whose urine, he insisted, was a perfect fixative for his drawings.

Despite this he had a frantically busy love life, conducting affairs with many of the models, prostitutes and society women who sat for him. At his death

aged 55, at the height of the Spanish influenza epidemic, Klimt was the

subject of no fewer than 14 paternity suits.

Perhaps for him, life as much as art was all about intimacy, the relationship

between artist and canvas and artist and sitter. Everything else was inconsequential.

“Whoever wants to know something about me as an artist, and that’s the only thing that matters,” he once said in an extremely rare moment of public

introspection, “must look attentively at my paintings and try to glean from them who I am and what I want.”