For a man who held no political office, ascended to no thrones, took no holy orders and attained no formal qualification of any kind, Grigori Rasputin maintains an extraordinary presence in the story of modern Europe.

He was long dead before the cold war, dead before the second world war and

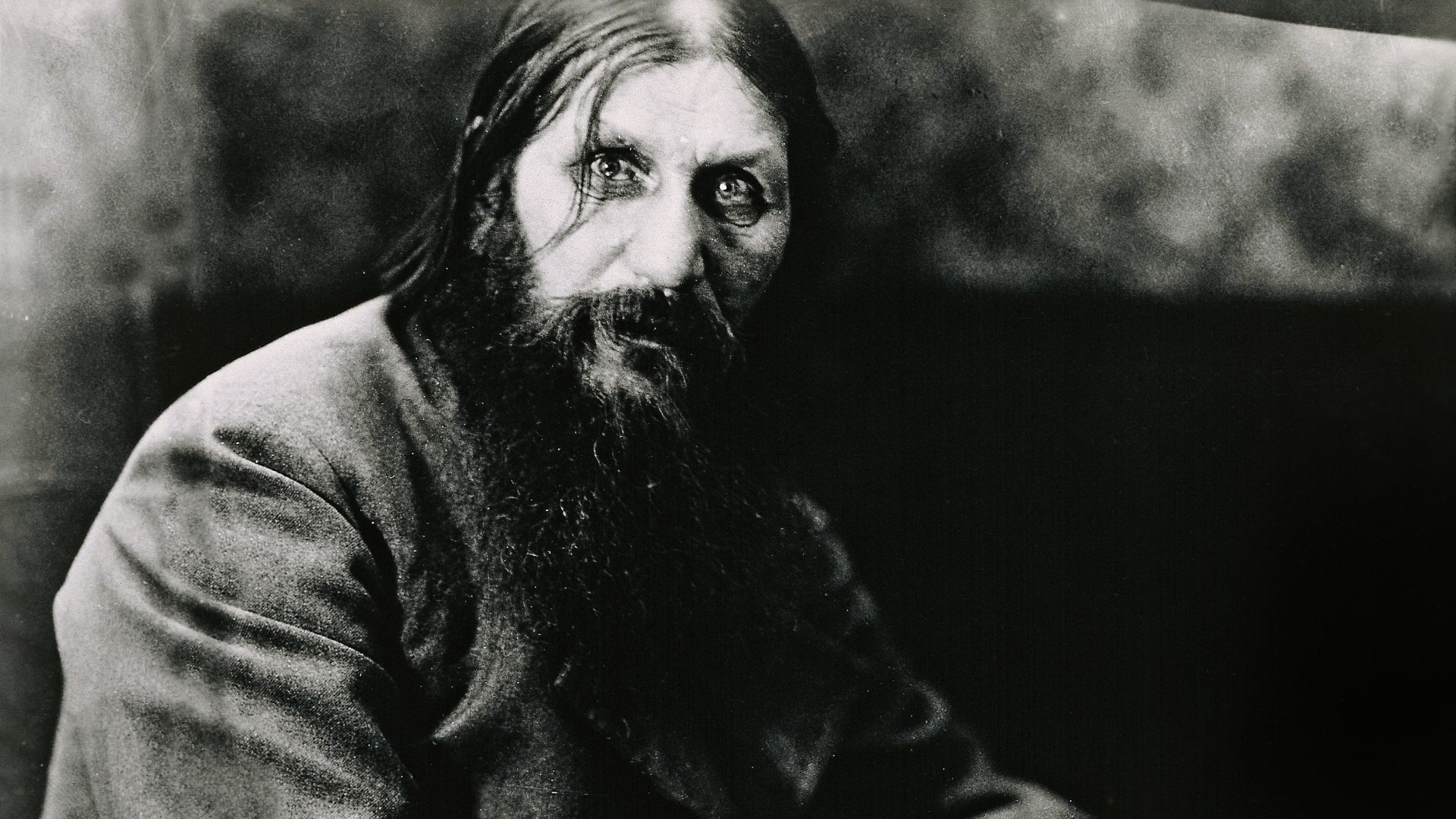

dead before the end of the first. He was dead even before the Russian Revolution, yet his influence seemed to touch all of them. Even now, more than a century after his much-mythologised demise, the self-styled holy man remains a vivid Svengali of modern history, his long, jet-black beard and wild, piercing eyes instantly recognisable even in the crudest of caricatures.

And what eyes they were. One contemporary account described how they “pierced you like needles”; another recalled them as “the green, rapacious

fires of a voluptuary”. A woman acquaintance spoke of how “it is impossible to withstand his gaze for long. There is something heavy in it, as if you are experiencing some sort of material force emanating from his gaze”.

Famously celebrated in song more than 60 years after his death as both Russia’s greatest love machine and the lover of the Russian queen, Rasputin’s

hold on the modern world remains strong enough that even today there are calls for him to be canonised. Those calls tend to come from extreme Russian nationalists but indicate what an influential and divisive figure he

remains more than a century after his body was pulled from the frozen Malaya Nevka river in St Petersburg.

Born into a peasant farming family in the tiny Siberian village of Pokrovskoe,

more than 2,000km east of Moscow, records suggest Grigori Yefimovich was the only one of eight siblings to survive beyond early childhood. By his late 20s, despite being married with a young family, Rasputin embarked on the first of a series of long pilgrimages, beginning with several months spent at

the Orthodox monastery of St Nicholas at Verkhoturye. Transformed spiritually by the experience, Rasputin became a strannik, a wandering pilgrim, forging a word-of-mouth reputation as a charismatic itinerant mystic with a gift for healing.

Having built a devoted following in Siberia, he won over the hierarchy of the Orthodox Church in the region who advised him to travel to the Russian capital, St Petersburg, and sent word to patriarchs there to expect him. Introduced in 1905 to a city social scene already fascinated by mysticism and the occult, it wasn’t long before word of the Siberian holy man reached the royal family itself.

In November of that year he was introduced to Tsar Nicholas II and the Tsarina Alexandra who, convinced of Rasputin’s healing powers, invited him

to treat their haemophiliac young son, Alexei. Rasputin produced what appeared to be positive results, and when he arrested a serious bleed in 1908, apparently through the power of prayer, he was fully embraced into the royal household.

It was then that the Tsar began consulting Rasputin on matters of state, a development that didn’t exactly enhance the reputations of either party in a nation already careering towards imperial collapse and political chaos.

Russia’s problems were manifold but it didn’t help that Nicholas was neither an assertive nor perceptive leader. When he began taking the advice of a famously libidinous faith healer it made both men fiercely unpopular with all levels of Russian society. Rasputin’s particular cachet among the women of the nobility made their husbands uneasy, especially with two key tenets of his teachings being intimate physical contact and an insistence that sinful

behaviour brought one closer to God as long as that sinful behaviour was carefully managed. By him.

Nobody was neutral on the Rasputin question. For his followers he was a miracle worker fuelled by love, for the rest he was a rapist and a heretic to

blame for everything from military setbacks in the war to the famines growing worse with every harvest. He had hypnotised the Tsar, they said, and conducted a sexual relationship with the Tsarina, consensually or otherwise.

For the people he was the embodiment of imperial debauchery and a prime

example of the need for revolution, for the nobility an opportunistic charlatan helping to destroy the state from within when it was already weak and vulnerable. Yet such was Rasputin’s charisma and influence he transcended criticism with an almost supernatural ubiquity. “Rasputin is everything, Rasputin is everywhere,” wrote the poet Aleksander Blok.

He was still mortal, though, and the end when it came was inevitable.

Rasputin spent his last day drinking in a bathhouse before making his way to a late-night appointment at the home of Prince Felix Yusupov to treat Yusupov’s wife, the Tsar’s niece Irina. But Irina was out of town. Rasputin walked straight into a trap.

According to the prince’s own account, he fed Rasputin cakes laced with cyanide and poured him three glasses of poisoned wine, none of which had any visible effect so Yusupov shot Rasputin in the chest and apparently killed him. When he returned with friends to dispose of the body, however, Rasputin leapt to his feet and forced his way past them, escaping into the street where he was felled by more bullets and his body rolled into the river. According to rumours that persist to this day – the official report is long lost – an autopsy recorded that Rasputin had died by drowning, was still alive when he entered the water and had even tried to claw his way through the ice that covered the frozen river.

In death as well as in life, the Rasputin story is shrouded in an awed mythology, making it difficult at this historical distance to separate facts from the enigma. Perhaps the most sober contemporary observations come from the writer and satirist Nadezhda Lokhvitskaya, known as Teffi, who dined twice with Rasputin.

He was “a semi-literate peasant and a counsellor to the Tsar, a hardened sinner and a man of prayer, a shape-shifter with the name of God on his lips,” she recalled in 1932, noting a hint of artifice in “the mysterious voice, the intense expression, the commanding words – all this was a tried and tested method”.

She described how “whenever he said something he would look round the whole group, his eyes piercing each person in turn as if to say, have I got you

thinking? Are you satisfied? Have I surprised you?”

Yet even Teffi, the detached and cynical chronicler of the follies and foibles of Russian society who found Rasputin “too twitchy, too easily distracted, too confused” to be a political svengali, couldn’t quite pin him down.

“How firmly and vividly his character is etched into my memory,” she wrote,

“and not simply because he was so very famous: in my life I’ve met many famous people, people who have truly earned their renown. Nor is it because he played such a tragic role in the fate of Russia. No. This man was unique, one of a kind, like a character out of a novel.

“He lived in legend, he died in legend, and his memory is cloaked in legend.”