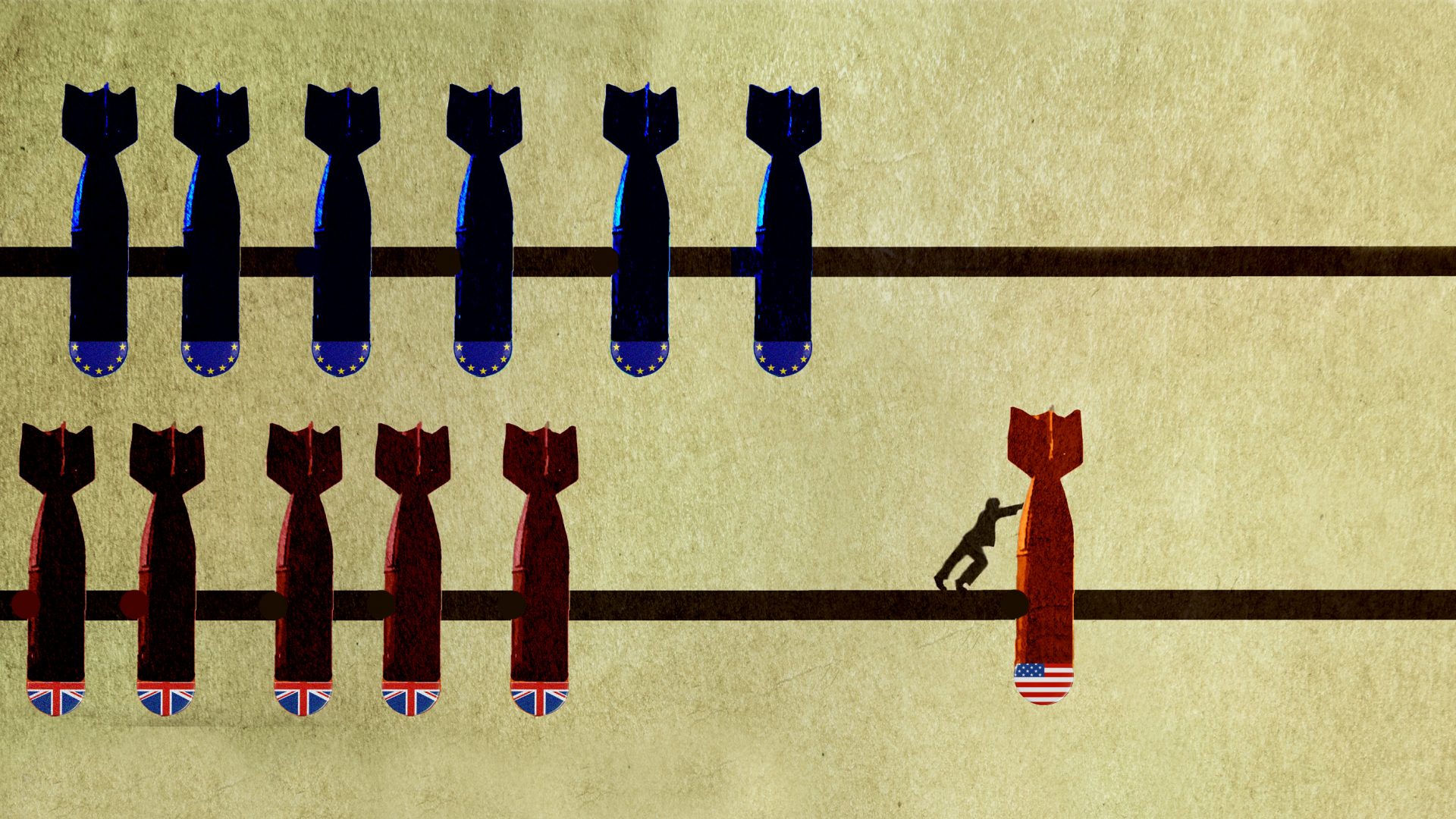

Europe’s leaders are reluctantly planning for the unthinkable: The withdrawal of America’s nuclear umbrella.

Friedrich Merz, Germany’s chancellor-in-waiting, has called for talks between the EU, and Europe’s only two nuclear powers – France and Britain – to strengthen the nuclear deterrent in Europe. Merz’s call has been echoed by Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk.

It should be stressed that trans-atlanticist Merz qualified his remarks on a European nuclear deterrent by adding that any European talks “should always be conducted from the viewpoint of complementing the American shield which, of course, we also want to see maintained.

For 76 years the United States’s nuclear arsenal has deterred an attack by the Soviet Union, and now Russia. Donald Trump’s willingness to abandon Ukraine, move closer to Russia and his threats of withdrawal from Nato, raise uncomfortable questions about America’s security guarantee.

At the heart of that guarantee are nuclear weapons. Any credible defense of Europe must have a nuclear deterrent at its core. Nuclear giant Russia cannot be deterred with tanks and drones alone.

The British and French have the weapons. What is missing is a credible strategy that: deters a conventional or nuclear Russian attack; replaces the American umbrella; convinces the Kremlin that they are serious; and assures European citizens that they are protected.

It was the Hungarian-born mathematician John von Neumann who in 1950 developed the theory and coined the phrase MAD (Mutual Assured Destruction). The term has governed East-West nuclear defense relations ever since. The acronym is appropriate, and is based on the belief that the two superpowers had to maintain enough nuclear weapons to destroy the other, no matter who struck first.

This was necessary to render the possibility of an attack insane – or MAD. The apparent recklessness explicit in the theory was the main factor in preventing not only a nuclear war but a conventional attack.

Over the years, a series of strategic arms limitation treaties (SALT I and II, START and New START) first limited and then reduced the American and Soviet/Russian arsenals. They have, however, left the French and British deterrents untouched, although their weaponry has been lumped in with the American arsenal in all the negotiations. This is why Russia has 500 more warheads than the US (500 being roughly the size of the British and French deterrents combined).

With the apparent American withdrawal from Europe, the MAD theory no longer applies for the defense of the European continent. That Cold War theory should be replaced by a nuclear policy first suggested by Charles de Gaulle: Minimum Deterrence (MIND).

De Gaulle imagined a nuclear policy that was totally independent, and that would protect France from all adversaries, not just the Soviet Union. Furthermore, it would be no larger than was necessary to inflict unacceptable damage on a larger adversary (suffisance stricte) and it would be used the moment the French government determined that there was an existential threat to France.

France’s current nuclear deterrent consists of roughly 300 nuclear warheads delivered by four nuclear submarines, each equipped with 16 missile tubes carrying M45 missiles. There are also two French air squadrons – one based in southern France the other in the northeast – of Mirage 2000 fighter bombers. Each is equipped with an air-launched cruise missile with a range of 500 kilometres.

READ MORE: The nuclear history of the bikini

The British nuclear deterrent is not wholly independent. It is operationally independent in that the British prime minister is the person with their finger on the nuclear button. But the deterrent of 250 warheads is based entirely on a nuclear submarine force of four Vanguard class submarines armed with US-supplied Trident missiles.

The British force is committed to the defense of Nato and foreign secretary David Lammy recently told Japanese television that Britain’s nuclear deterrent would protect Europe. President Emmanuel Macron has said that the French Force de Frappe would be extended to cover the rest of Europe and Friedrich Merz, Germany’s soon-to-be-confirmed chancellor, suggested that Germany would help to pay for any necessary extensions and improvements in the French and British nuclear arsenals in return for space under their umbrellas.

A European nuclear deterrent cannot, however, be effective without increased cooperation between Britain and France. The foundations for such cooperation were laid in 2010 when David Cameron and Nicholas Sarkozy signed an agreement for closer cooperation in nuclear matters, starting with a joint simulation center for the testing of nuclear warheads.

The agreement also made clear that joint testing was to be the first step towards further nuclear cooperation. One area that has been mentioned for future collaboration is joint submarine patrols. Such an arrangement could form the basis for a European nuclear deterrent force.

However, because of the British dependence on American missiles, the French Force de frappe would need – at least for the time being – to be the mainstay of a European nuclear deterrent. To be effective, the deterrent would need to balance credibility, security and political oversight that takes into account the multinational nature of Europe’s defence.

The first element would be political oversight in the form of a European Nuclear Council which could be linked to but independent of Nato’s Nuclear Planning Group. This would include representatives from nuclear and non-nuclear states. To be politically effective, the deterrent would require a dual-key system requiring joint authorisation from France and a strategic authority.

A supreme european nuclear commander would need to be appointed. They would be responsible for force readiness and the implementation of nuclear doctrine. Force readiness would include encrypted satellite and undersea communications, a network of hardened bunkers, maintenance of warheads and delivery systems, coordination between participating states and development of the deterrent.

The deterrent would also require a nuclear sharing agreement. The weapons would remain French and other European countries – all of whom are signatories to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty – would contribute to the maintenance of the deterrent either in the form of direct financial assistance or by contributing with air defense, delivery systems and/or other procedures.

Finally, a European nuclear deterrent needs a clear doctrine that sets out in unequivocal terms the circumstances under which nuclear weapons would be used. A MIND deterrence leaves little room for a second strike capability. Therefore, for a European deterrent to be credible it must be clear that it will be used to deter a conventional attack as well as a nuclear one. At the very least, it should fall back on the British policy of “strategic ambiguity” which refuses to divulge whether nuclear missiles would be used as a first or second strike weapon.

Brexit, coupled with long-standing British reluctance to be involved in a European army, means that in the short term, the British deterrent would play a tangential although vital role. Britain prides itself on acting as a bridge between continental Europe and the United States. It would be allied with both while being closely linked to the US through the provision of Trident missiles as well as through intelligence gathering systems and historic links. It is unlikely that even the most MAGA-fied America would refuse to aid Britain. If Europe were attacked, the UK would come to its assistance. And if Britain were attacked, the US would come to the aid of the UK – and, by association, Europe.

Greg Treverton is the former chair of President Obama’s US National Intelligence Council. Tom Arms is author of “The Encyclopaedia of the Cold War.”