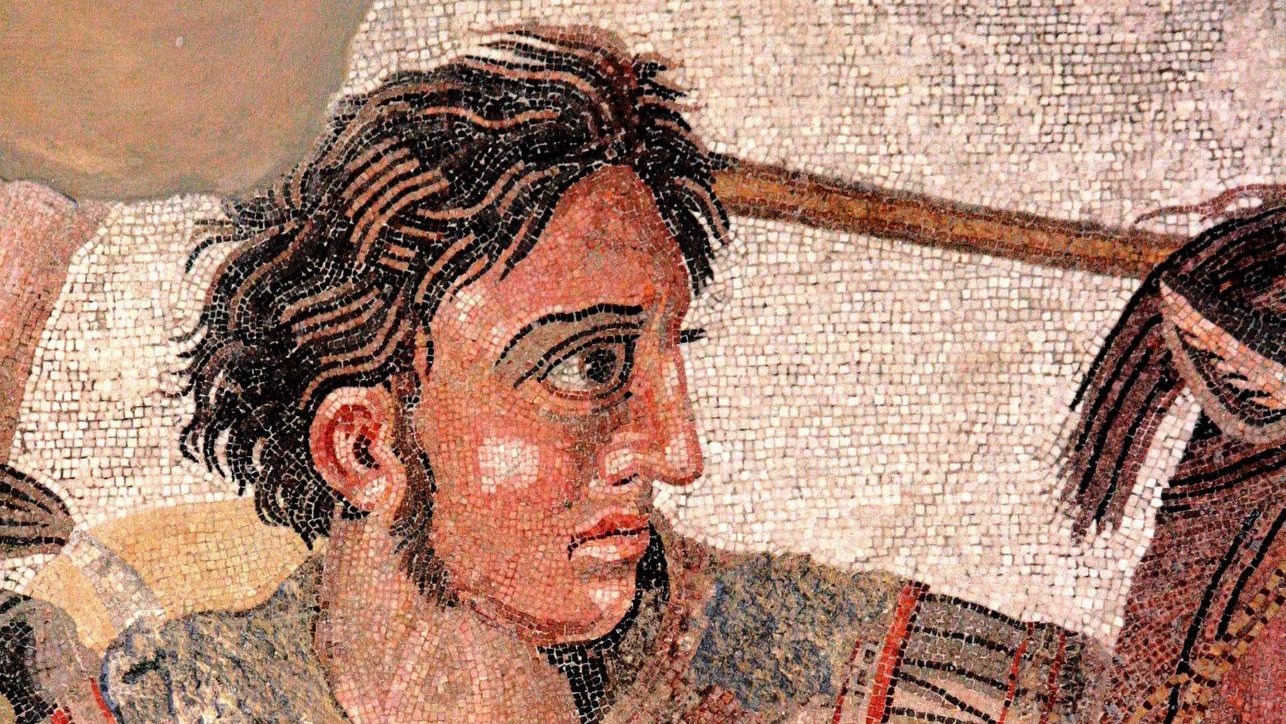

We might wonder what was so very “great” about Alexander of Macedon – he was after all an imperialist, militarist, colonialist, wrecker of cities, destroyer of civilisations, and perpetrator of massacres.

But there is no doubt that he was responsible for the way in which the Greek language and Greek culture first gained significance on the world scene, even though his mother tongue was Ancient Macedonian, not Greek.

Between 334BC and 332BC, Alexander’s conquests took him and his substantially Greek-speaking armies right across the Middle East and Iran into the areas which are now known as Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, parts of Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan, Pakistan and north-western India as far as the River Indus, some 5,000 kilometres from Greece.

As a result, the Greek language subsequently became vitally important as the main lingua franca – the language of wider communication – in a large area of the eastern Mediterranean.

Later on, even under the Roman Empire, Greek was the official language of the provinces of Libya, Egypt, Arabia, Judea, Syria and Persia, as well as of Greece and Asia Minor.

The widespread knowledge of Greek, and its use in writing the New Testament, greatly aided the spread of Christianity.

In Ancient Rome itself, Greek became the prestigious language of learning and cultivation – to the extent that upper-class Romans actually spoke it among themselves.

But what happened to the Greek language further east, beyond Asia Minor, after the decline and fall of the Hellenistic Asian kingdoms which Alexander left behind?

A community of Greeks had already been established in Bactria – a polity with its core in northern Afghanistan – since 494BC, 175 years before the arrival of Alexander.

Greeks had been taken prisoner and transported there from western Anatolia by the Persians, after a failed uprising against Persian imperial rule.

But when Alexander came across these Greek-speaking people thousands of miles from their original homeland, instead of congratulating them on preserving their Greek culture in such geographical isolation, his response was to massacre them – accusing them of treason.

From there, Alexander carried on to the South Asian subcontinent (never to return), leaving a garrison of 20,000 Greek solders behind in Bactria. A Greco-Bactrian kingdom survived for more than 200 years until it was overrun by Persianspeaking nomads.

The other major post-Alexander Asian Greek realms – Arachosia, which was focussed on Kandahar in southern Afghanistan, and the IndoGreek kingdom, which covered parts of modern north-western India and neighbouring areas of Pakistan – was also overrun by Central Asian nomads by about 50BC.

Then, it had been assumed, after 450 years, the Greek language no longer had any presence in Central and Southern Asia.

Except that, according to the historian Stanley Burstein, we now know that it did.

A short inscription in Greek has been discovered in Baghrãn, in Helmand Province in north-eastern Afghanistan, which can be dated to about 200AD, five centuries after the arrival of Alexander and seven centuries after the first arrival of Greek speakers in Central Asia.

More importantly, in 1993, a much longer inscription in Greek was found, which showed that the language had maintained its official status in Bactria until at least 100AD. This inscription was uncovered in northern Afghanistan by those other wreckers of cities and perpetrators of massacres: the Afghan Mujahideen.

Aléksandros

The English-language personal name Alexander comes from Greek Aléksandros, which is pronounced with the emphasis on the second syllable. The name was originally formed from the Ancient Greek verb aléxein, meaning to defend, plus the noun for “man” in the genitive case, andrós. The meaning, therefore, was “protector of men”