Scurrilous stories about Anita Berber still circulate today, almost a century after her death at the age of 29. Stories of how she would sashay into the lobby of Berlin’s exclusive Adlon Hotel wearing nothing but a fur stole, her pet monkey clinging to her neck and an antique silver pendant filled with cocaine at her breast.

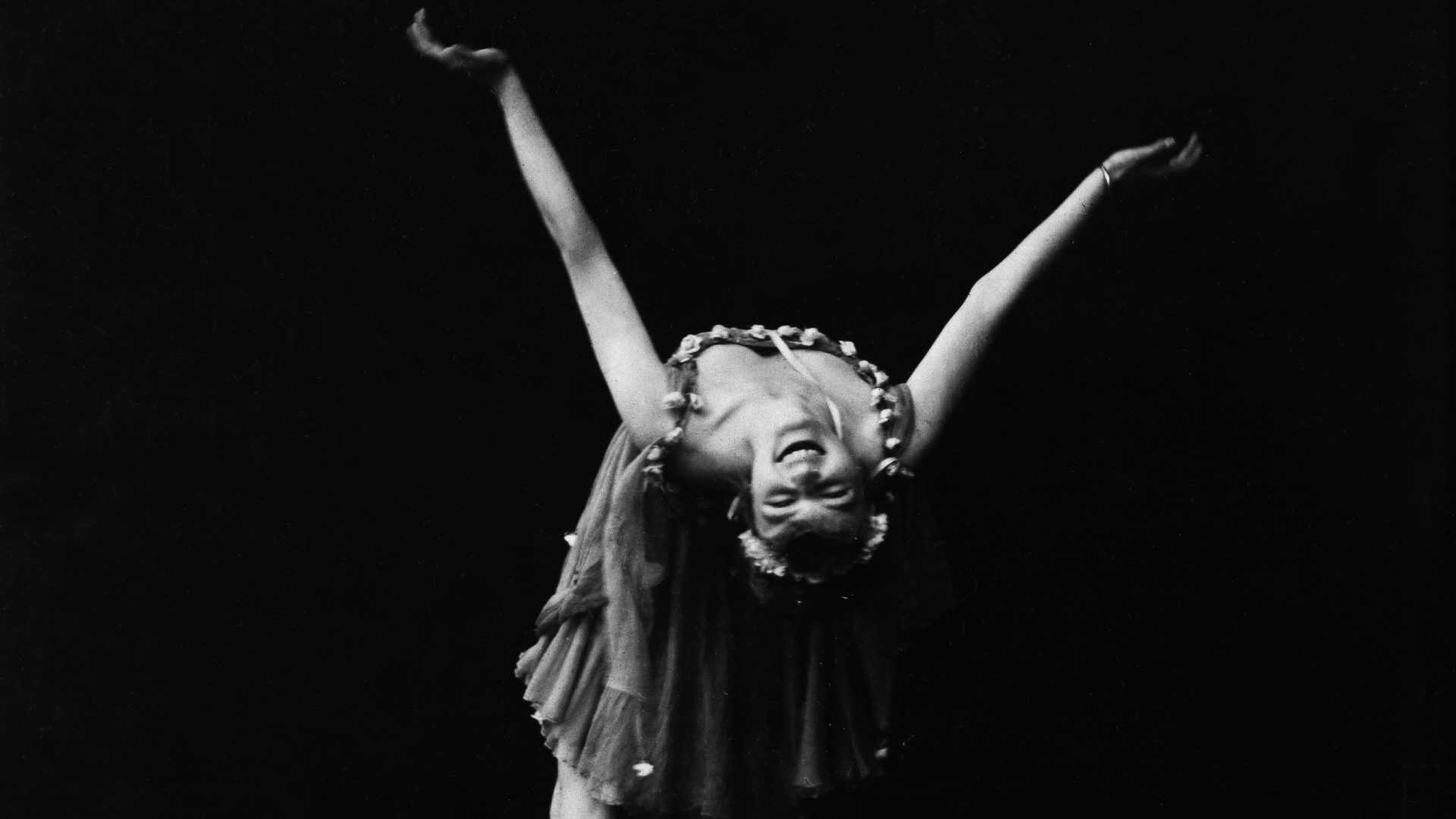

There were the scandalous cabaret routines in which she danced naked in self-choreographed exhibitions, with titles such as Absinthe and Morphine and would attack hecklers with an empty champagne bottle.

There was her androgynous wardrobe, the rumoured passionate affairs with the great and good of Weimar Germany – including Marlene Dietrich – the three marriages, the times she was expelled from Budapest for removing her clothes during a show to allow what she called “less restrained” dancing and was banned from Vienna for five years for her explicit performances. Not forgetting the occasion where she ended up in a Zagreb prison for six weeks after insulting the King of Yugoslavia.

On top of all that were her addictions to alcohol, cocaine, opium and morphine while her favourite stimulant was a bowl filled with chloroform and ether that she’d stir with a white rose and eat the petals.

On the face of it Anita Berber was the most Weimar of Weimar figures: decadent, impulsive, whimsical, a hedonistic, exhibitionist, a woman for whom every taboo was an invitation.

She looked like something from another world, never seen without thick make-up that whitened her face, her eyes rimmed with kohl and her lips painted the deepest red. It was the look of a film star, the kind of make-up worn for the primitive cameras of the day yet a look she took to the streets, emphasising her otherworldliness, promoting a sense that she wasn’t quite real.

But there was far more to Anita Berber than a scandalous life of rampant hedonism. She was a genuinely charismatic performer, a creative force of immense talent and a naturally gifted dancer. She had a presence on the stage, in photographs and in her appearances in some of German cinema’s most important early films. She was a beacon of female independence, forging a career entirely on her own terms through a body of work on stage, page and screen that was genuinely innovative. Her early death left the world wondering what she might have gone on to achieve had she lived.

The daughter of a concert violinist and a dancer who divorced when Berber was four years old, she first studied dance aged 14 at a school of contemporary performance in her home city of Dresden where she was brought up variously by her grandmother, friends of her mother and, briefly, in a children’s home.

When she moved to Berlin at 16 to study ballet it proved to be a perfect combination of time and place: by the time the Great War had ended and Berlin had established itself at the heart of an extraordinary cultural decade, Berber was reaching her creative peak.

By 1918, still in her teens, she had performed as lead dancer in a show at the Berlin Wintergarten, appeared twice on the cover of the groundbreaking women’s periodical Die Dame, made her screen debut in Das Dreimäderlhaus (The House of Three Girls), a biopic of Franz Schubert, and developed her own expressive, avant garde solo shows.

The following year she married Eberhard von Nathusius, a screenwriter from a wealthy family, and everything was in place for Berber to become one of the defining artistes of a defining decade.

In the spring of 1919 the newlywed Berber appeared in Richard Oswald’s Anders als die Andern, (Different from the Rest), a pioneering film in many ways, not least for Conrad Veidt playing the first clearly homosexual lead character in cinema history in a story of two musicians falling in love but falling victim to blackmail.

Soon afterwards she left her husband for the socialite and bar owner Susi Wanowski, who would become her manager and with whom she lived openly in a relationship.

By 1922, Berlin had emerged fully from the trauma of the war to establish itself at the cutting edge of European art and culture. It was then Berber met and subsequently married dancer Sebastian Droste, a man with whom she reached new heights of creativity and new depths of addiction. The couple put together a show called Die Tänze des Lasters, des Grauens und der Ekstase, (Dances of Depravity, Horror and Ecstasy), with an accompanying book of poetry, drawings and photographs.

For all their creative achievements, spiralling addiction led to the pair missing shows, breaking contracts and accepting multiple bookings for supposedly exclusive engagements, leading ultimately to expulsion from the powerful International Artists’ Union. Being barred from union venues forced Berber and Droste to the provinces and abroad, reducing their income while increasing their expenses and ultimately prompting Droste to disappear to the US on the proceeds of Berber’s pawned jewels -– leaving her practically destitute.

The following year, Berber, now 24, married her third husband, an American dancer named Henri Châtin-Hoffman with whom she created the duet show Tänze der Erotik und der Ekstase, (Dances of Eroticism and Ecstasy), which toured widely and provided the closest Berber ever found to a stable routine, albeit one still ruled by addiction.

In 1928 Berber was still on the road performing relentlessly, fuelled by little more than cocaine and alcohol.

On a tour of the Middle East that summer she collapsed during a performance in Damascus and was diagnosed with advanced tuberculosis.

The couple, broke and ailing, endured a gruelling journey back to Berlin where Berber died almost as soon as they arrived.

For all the decadence, the suites at the Adlon, the furs, the parties and the vast quantities of drugs, Anita Berber, the personification of Weimar Germany in all its sumptuous excess, was buried in a pauper’s grave.

The most famous image of her is a portrait by Otto Dix in which she wears a scarlet dress in front of a scarlet curtain and is presented as pot-bellied, haggard and much older than her years.

A better epitaph can be found in a dance routine from Fritz Lang’s Dr Mabuse, der Spieler, (Dr Mabuse the Gambler), made in 1922.

In a cabaret scene, Berber, in a tuxedo, dances alone to a band that, bouncing and gurning, looks ridiculous in the absence of sound.

Berber meanwhile sways, swings and shimmies through the silence, using the entire width of the screen, perfectly balanced and in control of every part of her body, her dancing feet a blur, her upper body almost completely still, lost in her own movement and a rhythm we can’t hear, her face a picture of calm contentment as if nothing in the world matters beyond the edges of that dancefloor.