Is there a single defining image of Brexit? The one that stands out for me is not of a victorious Nigel Farage with arms aloft on referendum night, or border queues or empty shelves. It’s of what its photographer describes as “a Brexit Statue of Liberty figure… the first thing you see when you approach Great Britain by sea – this wonderful middle-aged man in a dress and a bonnet waving at you while holding a union jack, welcoming you to the promised land.”

The picture of Grayson Perry features in Muse, a new book that collects a decade’s worth of images of the artist-broadcaster-national treasure by award-winning photographer Richard Ansett. “We were planning the shoot at a time of horror, extraordinary tension after the referendum, and I was thinking of a set piece about cliches of Britain like the White Cliffs of Dover and how to open up ideas of what Britishness can be,” he says. “But how do you sum that up in one picture? And as the idea developed it became so good that I couldn’t have taken the heartbreak if it didn’t come off. I was saying: ‘If we don’t do this, I’m going to burn people’s houses down – sorry, everyone dies unless we do this’.

“Grayson said yes, and so I had this amazing gift of his persona to temper the rabid nationalism and the toxicity of the union flag. And of course, we had a literal cliff edge. And the place we shot it, Seven Sisters cliffs on the South Downs is a suicide spot – it is literally at the spot where people jump. The shoot was fantastic. There’s Grayson in his handmade dress, with a £2 union jack that I stuck into his hand. At that time, it just was extraordinary to be there with this wild cackling genius of an artist coming over the hill in his dress and bonnet.”

Perry calls the book a mix of “ridiculous fantasy and crumpled reality” – which might sum up Brexit almost as well as that photograph. “As the subject I look at these photographs with joy in that they are funny and delightful and horror in knowing that I am that raddled old trannie,” he adds.

For Ansett, whose subjects have included female prisoners at HMP Foston Hall, the first same-sex couples to obtain civil partnerships in London and child survivors of Grenfell Tower and the Manchester Arena bombing, the book is not just a collection of photographs of one man, but “an opportunity to examine what the hell has been going on between him and me and us all over the last 10 years.”

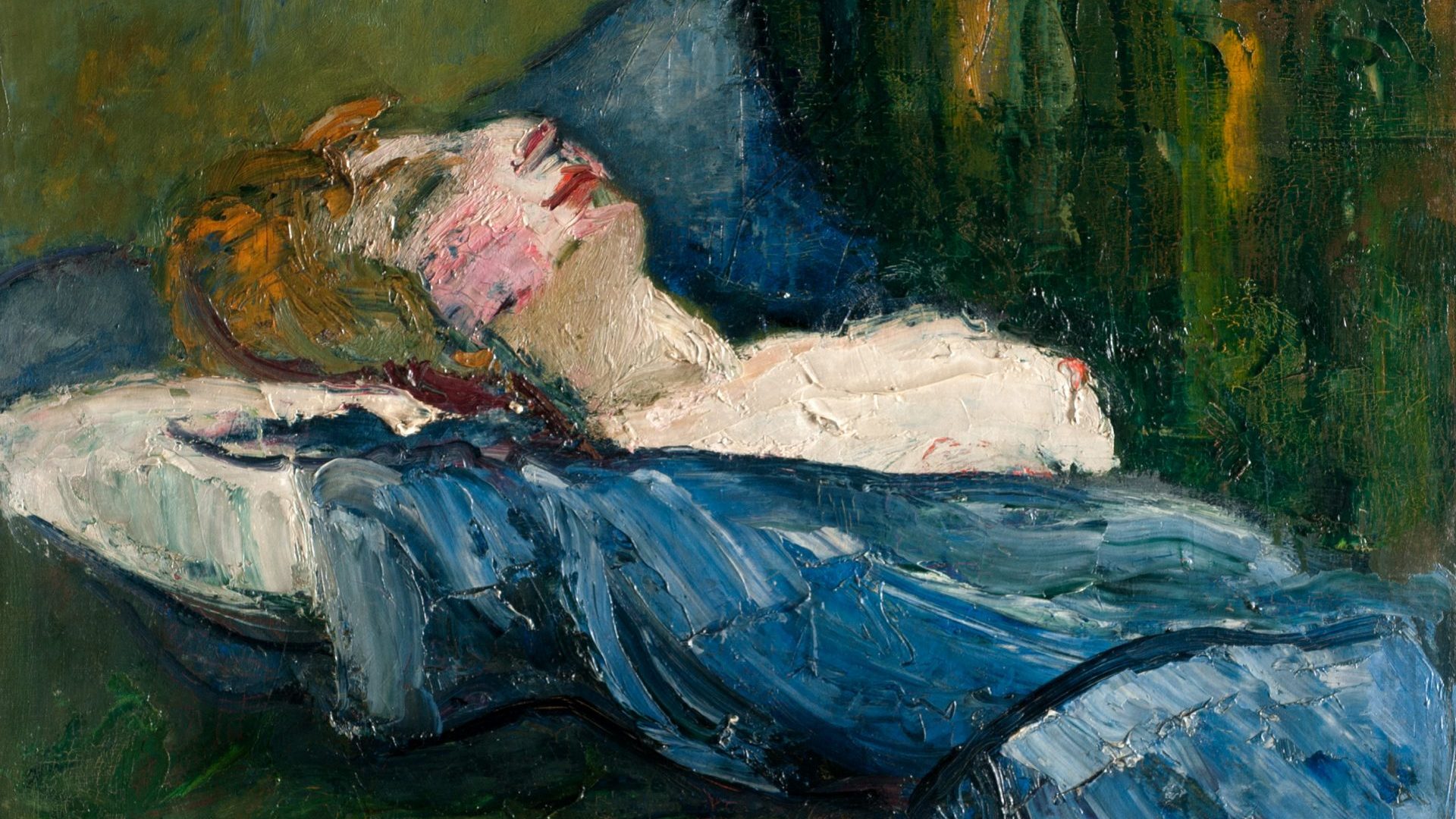

There are memorable images that evoke the surreality of Donald Trump’s White House years (a triumphal Perry in a gingham dress with a Harley-Davidson and the stars and stripes behind him) and the dilemmas posed by gender-based culture wars (Perry as the Madonna, with child). Created in part to promote the artist’s successful Channel 4 documentary series, they serve as beautiful, simple echoes of the themes he explores in his pottery and epic tapestries.

Ansett’s pictures also chart a decade in which he says Perry, who won the Turner Prize in 2003 but was then far from a household name, has “seeped into the national consciousness” in a way few British artists have ever managed. The dresses and makeup help, of course, but so does Perry’s inquisitiveness about those he might naturally be at odds with, as seen on those documentaries, and the generosity of spirit he displays in the Grayson’s Art Club TV show, which became a lockdown sensation. Having sold out large theatres on a recent tour, he seems to be easing past the status of an easily recognisable eccentric – like Gilbert & George – and is approaching the ubiquity of a British Warhol or Dalí.

“I think he’s increasingly sort of national treasure material, rather than this sort of obscure, complex existential artist that no one fully quite gets,” says Ansett. “I think Art Club, which was very warm and comforting and joyful, offered support to people when they needed it and Grayson’s humility and humanity has made this person who is clearly different accepted by the mainstream.”

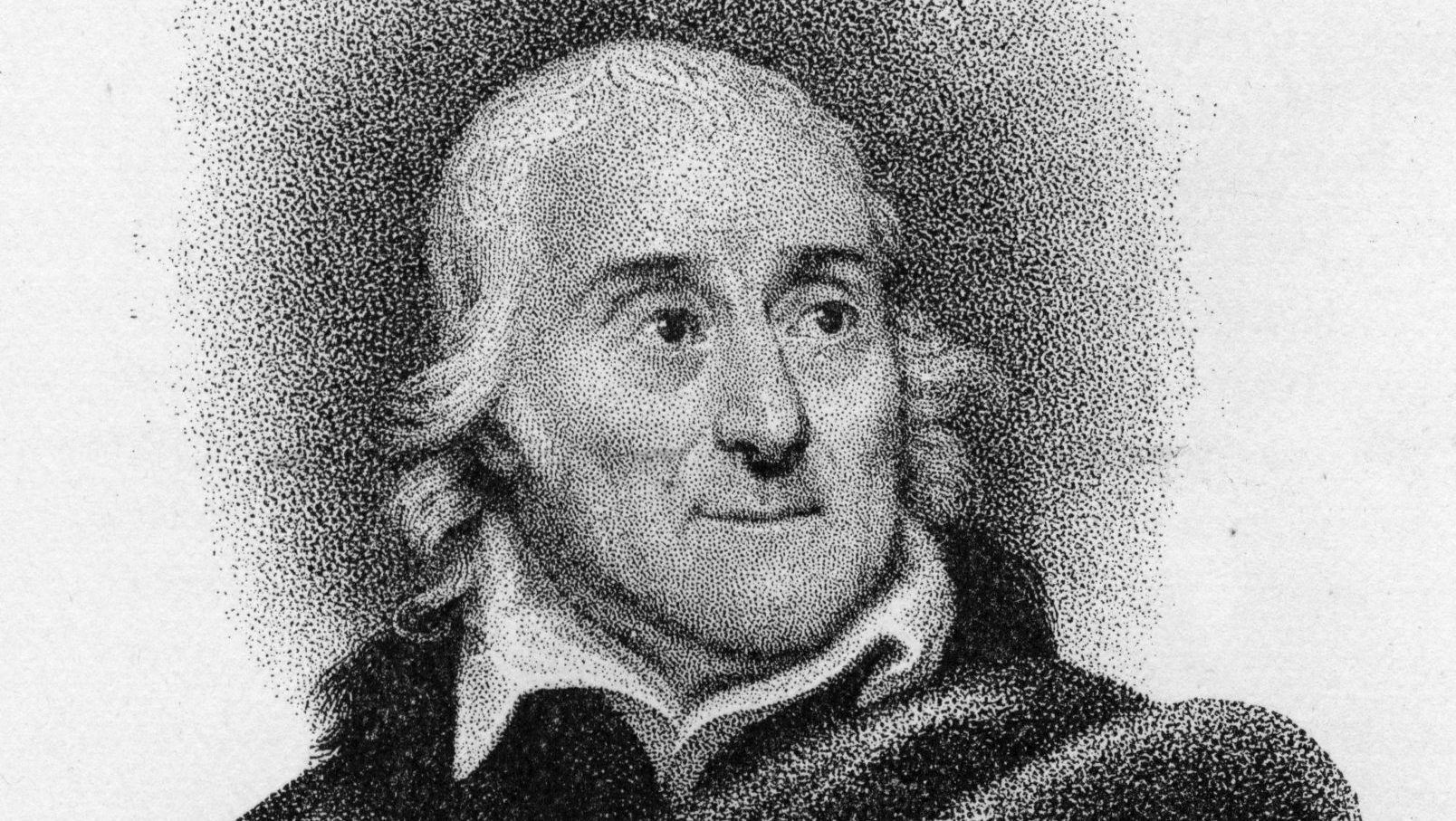

Ansett’s first images of Perry, taken before the artist’s Reith Lecture at Tate Modern in 2013, show him in a “blood-red womblike room. Grayson is clutching his handbag, he’s looking at me with horror because he’s expecting to be given direction, but I’m not speaking to him. Someone described that picture as him looking like he was being mugged at a cashpoint. It went into the National Portrait Gallery more or less straight away, a huge chance for a photographer. And it made me think, ‘well, what do I do next with this guy’?” What’s next right now is a project for London’s Wallace Collection, involving Perry as a Victorian ghost.

“There must be a reason why he keeps asking me back,” continues Ansett. “His wife Phillippa is a psychotherapist and I’ve done Gestalt therapy and been a Samaritan for 20 years, so that’s one link. And I do think that we have a common interest in British society and real people, like my photographs of the children of Grenfell Tower and things like that. But when I photograph him we don’t sit around discussing psychology. It’s a fun event; as soon as you’ve got the camera out he just becomes this spirit of chaos, spirit of joy, shouting and flying around and putting costumes on.”

Muse: A Portrait of Grayson Perry by Richard Ansett is available now from ACC Art Books, price £40