Where are the champions of the arts in the UK? Who will stand up for them? That’s what I found myself wondering when deep cuts were announced to the budgets of opera companies and theatres in London. It was left to the dazed spokespeople of these outfits to gather their wits and express disappointment after Arts Council England (ACE) reduced its spending in the capital by £32 million. ACE distributes government money and funding from the National Lottery to arts organisations.

In making their savings, the chair of ACE, Sir Nicholas Serota, and his colleagues were taking their cue from Nadine Dorries, the former Culture Secretary. She had instructed the funding body to support the levelling up agenda initiated by Boris Johnson (the former prime minister-but-one) and favour communities outside London over art lovers in the metropolis and overseas visitors.

These cuts are in marked contrast to the boost in arts spending pledged by European governments. Earlier this autumn, the French arts minister, Rima Abdul Malik, announced a record budget of £3.86 billion for culture, an increase of 7 per cent. She said ministers were acting to help the sector as it recovers from the effects of the pandemic. She went on, “What will happen to our cinemas, bookshops, theatres, museums and opera houses in 20 years’ time? What kind of audiences will frequent them? What would our society look like if these places were destined to become empty?” And her German counterpart Claudia Roth also promised an uplift of 7 per cent in arts funding, bringing the total government spend to £2 billion. Roth said, “The members of the Bundestag are specifically strengthening the arts, culture, and media in the face of the unprecedented crises of our time. Now more than ever, we need the open spaces for discourse and the diverse food for thought provided by art and culture.”

The entire sum disbursed by ACE to almost 1,000 arts bodies around the country is only £446 million. The new Culture Secretary, Michelle Donelan, has made no public comment on the ACE cuts. They entail the English National Opera losing its entire grant of £12.6 million. The company will have to move out of London, perhaps to Manchester. What the French arts minister feared for the theatres of Paris will come to pass for the ENO’s magnificent Edwardian home, the Coliseum, perhaps the finest playhouse in London, which will now stand empty. The chief executive of the ENO, Stuart Murphy, declared himself “slightly confused”. The opera company already offers free seats for under-21s and has made great efforts to attract diverse audiences, both desirable outcomes by ACE metrics.

The Royal Opera House also had its backing cut by more than £2 million a year. The Donmar, the theatre where director Sam Mendes made his name, had all of its funding of more than £500,000 a year withdrawn. A similar fate befell the Gate Theatre in Notting Hill and the Barbican Arts Centre. Support for the National Theatre has been cut by 5 per cent, from £17 million a year to £16.2 million.

The Sun was quick to report that those on the receiving end of ACE largesse include the National Football Museum in Manchester, which will get £350,000, and the famous Blackpool illuminations, earmarked for £225,000.

If the axe had fallen on scientific bodies instead of cultural ones, it’s not hard to imagine the media turning to well-known and widely admired individuals like Sir David Attenborough or Professor Brian Cox for comment. They have powerful voices in any debate over the future of science funding in this country, and a quango or minister crosses them at their peril. Trusted figures with a scientific background have status because we count on them to level with us about pressing issues such as Covid and global warming. Withdrawing support from a theatre here, reducing an opera company’s budget there, doesn’t have the same news value. And pressure groups for the arts don’t begin to match climate campaigners for stunts, which provoke the public and get politicians’ attention.

You’d be hard put to make the case for the arts in life-or-death terms. But we don’t have to. It’s enough to say that the culture sector supports thousands of jobs, attracts tourists, contributes billions to the national coffers, boosts mental health and furnishes the next generation with valuable and transferable skills. Few people would deny any of that.

And yet the arts are under pressure everywhere, with few prominent names to defend them. Future historians may conclude that the present moment was decisive in the dismantling of the consensus over culture’s position as a civic good. This consensus was highly patrician. Tories who trod the boards in Footlights at Cambridge were happy to put public money into the Royal Shakespeare Company. Trade unionists who read Gramsci and Richard Hoggart on subsidised degree courses became Labour MPs and voted for public libraries. The arts are no longer a matter of noblesse oblige, and that’s no bad thing. But who will stand up for them when the tough spending choices are made? In living memory, the Culture Secretary was a figure with some connection to the arts: Grey Gowrie, who did the job in Mrs Thatcher’s Cabinet, was a well-regarded poet. By contrast, Dorries’s CV included munching an ostrich’s anus on the reality show “I’m a Celebrity”, although in fairness, she has also written several books of popular fiction. The present incumbent, Ms Donelan, had a stint as a marketing manager for the grappling franchise, WWE.

Leaders of artistic institutions have spent the last few years preoccupied by lockdown and reduced takings as well as ticklish questions of identity and heritage. Who should be remembered with a statue and who deserves to be dunked in Bristol docks, like the effigy of the slave trader Edward Colston? Are the Parthenon Marbles and Benin Bronzes best displayed in the UK or are they blood-soaked booty which must be repatriated? As debates have raged over decolonising the arts, theatres and opera companies have been reviewing their repertoires, casting choices, sponsors and so on. Arts leaders could be forgiven for taking their eyes off the core business of keeping the lights on and the doors open.

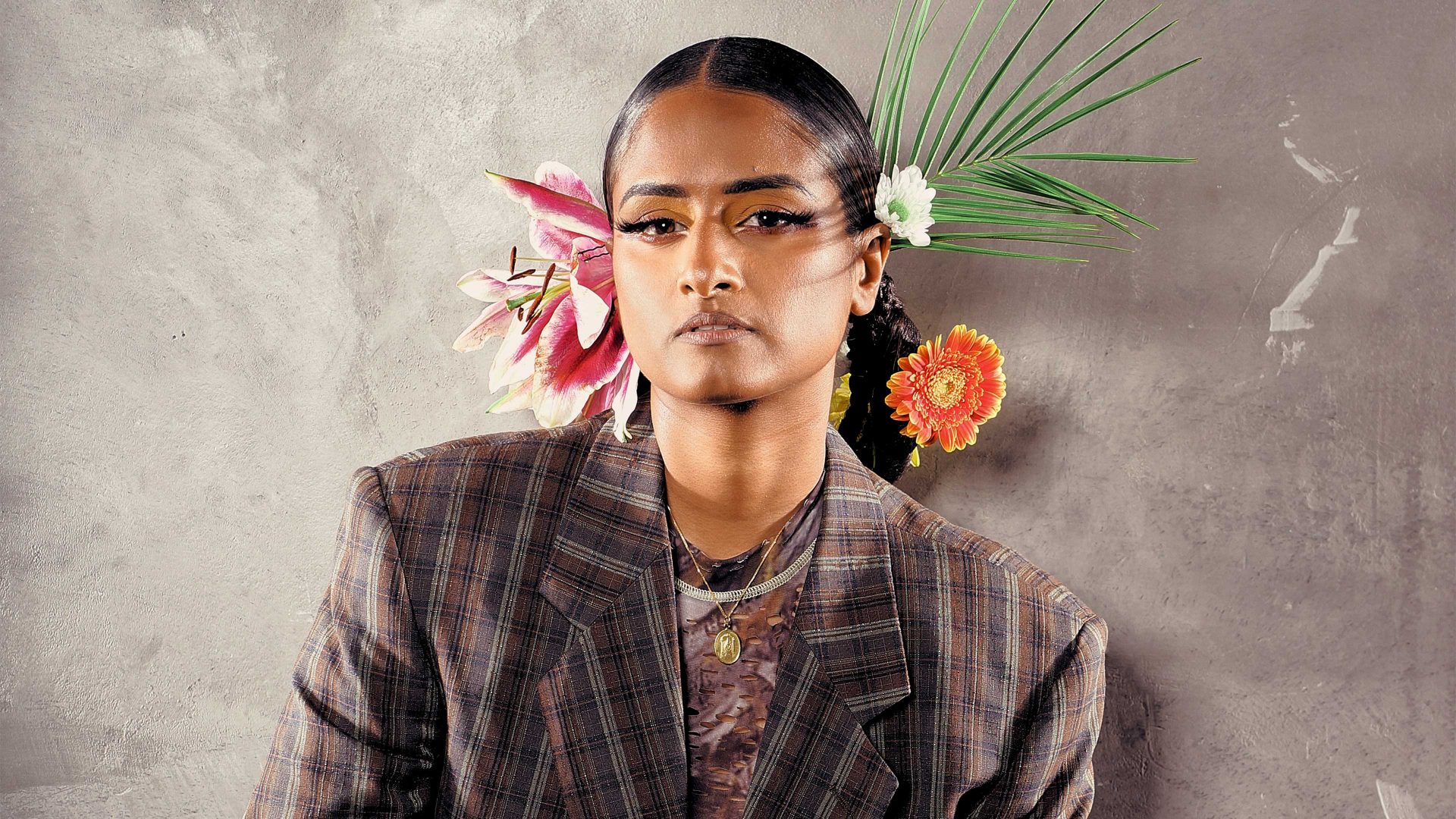

Mezzo soprano Jenifer Johnson feels so strongly that the argument for opera is not being made that she’s doing the job herself, even though she’s almost 4,000 miles from London in Minnesota, where she’s currently giving performances of Mahler’s Third symphony. Johnson is lobbying sympathetic MPs to challenge the ACE cuts. Born in Liverpool, where she still lives, she has been nicknamed the “Scouse diva”. She has won the Royal Philharmonic Society’s Singer of the Year award and picked up Recording of the Year at the Gramophone Awards 2022. Even though she’s a proud northerner, Johnson told me that she regrets ENO’s likely move to Lancashire. “We already have Opera North in Leeds. Putting the ENO in direct competition in the next city along makes a nonsense of Opera North’s remit.” Moving a company of the size of the ENO – not just its musicians and performers but also technicians and other behind the scenes staff – really means breaking it up, says Johnson: by no means everyone will be able to relocate to Manchester. She sees an irony in a Brexit-supporting government putting a squeeze on the ENO, which was established in 1931 to perform works sung in English rather than Italian, German or French, the traditional languages of opera.

Johnson said, “Opera is a very expensive art form. You might have 100 people – musicians and performers – on stage, and as many again behind the scenes, working in costume, design, etcetera. In Europe, they might spend €25 million on a big opera. When you see the total government funding for the Royal Opera House is £24 million, it makes their achievements miraculous.” Not only that but you can see a production at the Royal Opera House for just £3, provided you’re prepared to stand.

Johnson calls the choices made by ACE “aggressive, ill-thought out and incredibly damaging in the long term. I don’t agree that this is a government of philistines: Michael Gove likes to go to the opera. But he keeps quiet about it.” In July, Dominic Raab, Gove’s colleague around the Downing Street table, called the Labour frontbencher Angela Rayner a “champagne socialist” for attending Glyndbourne during a rail strike. Johnson says, “They think that opera is elitist but they’re confusing elitism with excellence.”

London is a centre of quality in music, producing great musicians and touring companies as well as first-rate technicians – but for how much longer? Johnson says that opera and classical music strike a chord with the public, and politicians should pay attention. “Everyone noticed the choral music which was performed at the Queen’s funeral, people commented on it. Can you imagine what the coronation of King Charles would be like without it?”