By the time the Wannsee Conference took place on January 20, 1942, the German people were starting to feel the abomination of war. After cherishing from afar Hitler’s swift and, for the Germans, almost painless victories in Poland, the Benelux area and France, people began to look anxiously at the sky. War was coming close to their own homes, in the form of devastating air raids by the RAF.

Mannheim, where my grandparents lived, was one of the most bombed cities in south-west Germany because of its strategic position at the confluence of the Rhine and the Neckar rivers, its harbour and its industrial infrastructure.

But the British aimed for the densest residential areas, too. My grandparents’ home was hit several times and as soon as air raid warnings sounded, they had to run to a bunker built by the Nazis for party members. My grandfather had this privilege because he was a Nazi.

Most other citizens had to take refuge in crowded bunkers throughout the city. After the bombings, the citizens emerged like zombies, looking at dust, ruins and flames. Some of them began to say: “This is the revenge of the Jews.”

In October 1940, the first mass deportation of Jews from Germany had taken place in the exact region where my grandparents lived.

More than 6,500 men, women and children were deported to the French internment camp of Gurs, in southwest France, administered by the French Vichy regime, who collaborated with the Third Reich. Among them were two families my grandfather Karl knew well: the Löbmanns and the Wertheimers.

In August 1938, he had bought their business, a small oil company, at a low price, taking advantage of the Nazis’ anti-semitic measures. My grandfather negotiated a discount of 10 per cent on what was already a bargain price, set low because otherwise the Nazi authorities would not have validated the sale.

Karl Schwarz was not a convinced Nazi and held no office in the regime – he was too much of a hedonist to adhere to the Nazis’ disciplinary sadomasochism. But he was an opportunist.

While Jews were in urgent need of money to escape abroad, others abused the situation far worse than he did. Yet he was also not one of the ‘goodwill buyers’ who bought businesses from Jewish friends or bosses to keep them safe until a time when they could be returned for the same amount that was paid. Nor was he one of those who paid an extra amount under the table to top up the sale price to a fair amount. Karl Schwarz took his chance when it presented itself.

Like him, during the 1930s, millions of Germans became interested in the so-called ‘racial cause’ of the Third Reich when they saw a chance of personal gain. The exclusion of Jews from most official positions and professions opened up coveted positions in universities, academies of sciences and arts, administration and banks. It freed non-Jewish entrepreneurs, lawyers, doctors, and shopkeepers from competition.

Many who did not take direct advantage of the Jews’ distress were guilty of indifference and conformism and a certain amount of convenient blindness.

My grandmother was not part of any Nazi organisation but loved Hitler and the new opportunities the National Socialist regime opened up for the lower middle-class, such as a subsidised cruise to Norway on a new liner – an unheard-of luxury at the time for a woman of her social status.

The deportation of Jews made it possible to acquire, for a pittance, their businesses, flats, works of art, furniture and jewellery, lining the pockets of many buyers and intermediaries. After the Jews of Mannheim had been deported, the contents of their flats were sold at auctions, often held in the original apartments, so buyers must have been acutely aware of the people who had once lived there.

My father suspects his father acquired all their living room furniture at such auctions. I imagine him intruding like a thief into those homes, filled with traces of a last-minute departure: Children’s toys scattered on the floor, coffee cups on the kitchen table, family photos still on the wall.

A gold-rush atmosphere electrified the country. Even propaganda minister

Joseph Goebbels was surprised to see how his compatriots were plunging “like vultures on the warm crumbs of the Jews”.

By opportunism, greed, conformism or indifference, tens of millions of Germans became mitläufer – German for fellow traveller; accomplices of a criminal regime, allowing their monstrous enterprise and feeding a spiral of violence and hatred that would lead to the worst.

By the time the 14 senior representatives of the German government, the occupied territories in the East, the Nazi Party and the SS met in a magnificent villa on the shores of Lake Wannsee in the suburbs of Berlin, the Holocaust was already well underway. The aim of the conference, convened by the head of the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA), Reinhard Heydrich, was to define a practical plan of how to proceed and coordinate the actions of the many services involved in mass murder.

The meeting was secret, but a copy of the detailed minutes – written by the expert from the Department of Jewish affairs and evacuation, Adolf Eichmann – survived the destruction of the archives undertaken by the Nazis at the end of the war to erase all traces of their crimes.

At his trial in Jerusalem in 1961, Eichmann confirmed that the minutes were “an exact reproduction of the content of the conference’’ and that the euphemism “final solution of the European Jewish question” unequivocally meant “killing, eliminating and destroying’’.

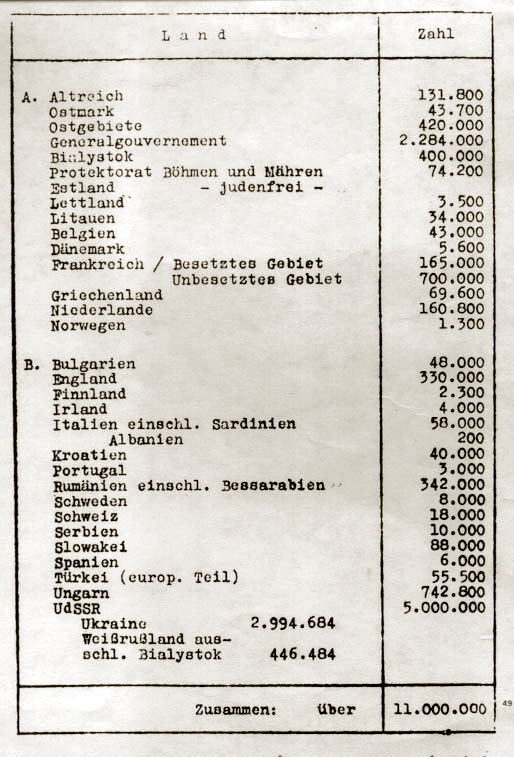

The participants discussed the areas of competence of each department, the measures to be taken and the course to follow for the deportation of the European Jews to the East and their subsequent extermination. They also aimed to clarify the target populations: All Jews, even those who had converted to Christianity generations earlier, with the exception of “quarter-Jews’’, as well as “half-Jews” provided that they were married and had offspring with a German blood partner. A total of 11 million people were identified, including those from countries not occupied by the Reich, such as Switzerland, Great Britain and Turkey.

Eichmann had collected the statistics and compiled a country-by-country list, subtracting the Jews already murdered in the Soviet Union as part of Operation Barbarossa, especially in the Reichskommissariat Ostland (RKO), which included the Baltic states and part of Belarus. This focus on data and process in pursuit of the darkest ends would later be noted by author Hannah Arendt, who after Eichmann’s trial coined the phrase “the banality of evil”.

In a report sent shortly afterwards to Heydrich, the SS leader of the RKO Franz Walter Stahlecker summed up his performance with a map marked with small coffins flanked by the number of Jews already murdered – 218,250 – and proudly indicating in capital letters that Estonia was “JUDENFREI” – free of Jews.

The Wannsee Conference lasted only 90 minutes. Apart from Heydrich, none of the Reich’s top leaders of the bodies involved were present.

It was left to their subordinates to deal with the bureaucratic and technical aspects.

This presupposes an upstream decision, as a matter of such importance could only be agreed at the highest level. But when, how, by whom and why was the extermination of the Jews decided?

No Führerbefehl (Fuhrer Order) clearly giving the go-ahead for genocide has ever been found. Had Hitler been plotting a master plan for a long time? Or did the Nazis decide the fate of the Jews as and when the Reich’s military situation developed?

In the 1960s, a controversy emerged around these questions, dividing historians into two factions. Some argued that Hitler had a long-standing plan, identifiable in his writings and statements, and that without the Führer there would probably have been no Holocaust. Others believed that the genocide was the result of the immediate circumstances, particularly military, in which the Nazis found themselves and also of initiatives taken at a lower level of the hierarchy, including on the ground.

Today, most historians take a more nuanced view and agree that the genocide cannot be attributed to a single decision taken at a specific time but was the result of a prolonged and cumulative process, including local initiatives.

There is also a consensus on the central role that Hitler’s anti-semitism played in the Holocaust. He never made a secret of his pathological hatred of Jews, neither in Mein Kampf nor in his speeches, as a member then leader of the Nazi party in Munich.

Although born in Austria, Hitler was almost religiously devoted to Germany, which he served on the Western Front in the First World War. Like many of his contemporaries, he was traumatised by the German defeat and the Treaty of Versailles, which imposed heavy sanctions and reparations on Germany.

He became a follower of the Dolchstosslegende, the stab-in-the-back legend popular in the army and among right-wing nationalists and according to which Germany’s surrender, far from being a defeat, was the result of treachery from within, with the blame resting on the Social Democrats, communists and, in particular for Hitler, Jews.

Fuelled also by the delirious and contradictory theories of a Jewish-capitalist and Jewish-communist world conspiracy, which had been circulating ardently in Russia and Europe since the end of the 19th century, Hitler’s anti-semitism became more radical. In his speeches, he called for “tearing out the evil at the root”, and “removing” and “eradicating” the Jews, whom he compared to “tuberculosis bacilli”.

But it was not until January 30, 1939, that he made his first genocidal threat, declaring in front of the Reichstag: “If the international Jewish financiers in and outside Europe should succeed in plunging the nations once more in a world war, then the result will not be the Bolshevisation of the Earth and thus the victory of Jewry, but the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe.”

Several historians have noted, however, that Hitler did not seem to be in a hurry to carry out this genocidal threat. It was only on December 12, 1941, when he gathered the leaders of the Reich and the Nazi Party shortly after the entry of the United States into the war, following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, that Joseph Goebbels noted in his diary: “The Führer’s prophecy is being fulfilled in the most terrible way… the world war is here, the extermination of Judaism must be the necessary consequence.”

But until 1941, another option, the “territorial solution”, was under consideration: the mass deportation of the Jews, to be settled far from Europe.

To this end, after the invasion of western Poland in September 1939, which placed about two million more Jews at the disposal of the Reich, the Nazis began to concentrate them in ghettos in large cities near railway lines.

In the spring of 1940, as Nazi Germany invaded the neutral Benelux region and prepared to conquer France, a plan long in vogue in European anti-semitic circles suddenly seemed within reach: The deportation of millions of Jews to the French colony of Madagascar. But continuing war with Britain, whose navy dominated the seas, made the plan unfeasible. Other destinations were envisaged far to the east, but only vaguely. There was also no point in thinking about the mass immigration of Jews into host countries: the international community, from the United States to Australia, via South America.

During the course of 1941, the idea of the mass destruction of the Jews took shape more and more clearly. The ghettos in the east were full to bursting, tens of thousands were dying of hunger and epidemics, the Nazis could not respond to the situation.

The radicalisation reached a point of no return when on June 22, 1941, against the advice of part of his general staff, who feared the opening of a second, uncontrollable front, Hitler launched an invasion on a scale unprecedented in military history: Operation Barbarossa.

More than 3.3 million Axis troops were deployed along a front stretching from the Baltic Sea to the Carpathians. The soldiers to whom Hitler had

promised a blitzkrieg like on the Western front, a victory at lightning speed before winter, got bogged down and stuck in the mud of the Russian autumn, then found themselves trapped in the middle of a freezing winter, without gloves or warm coats, in front of a fiercely resisting Moscow.

This war not only aimed to guarantee Germany lebensraum (living space) in the east, but also to annihilate “Jewish Bolshevism’’, an amalgam that would motivate and justify massacres on a new scale.

With the invasion of the western part of the Soviet Union, including Ukraine, Belarus, Bessarabia and eastern Galicia, more than 2.5 million Jews, on top of the already enslaved Polish Jewry, fell into the hands of the Nazis. Most of them would not survive.

On July 31, 1941, Heydrich was commissioned by Hermann Göring to draw up a ‘global project’ concerning the costs, organisation and execution of the ‘‘final solution to the Jewish question’’. He deployed Einsatzgruppen – mobile killing squads – with 6,000 men on the eastern front, which, in the wake of the Wehrmacht advance, were given the mission of rounding up Jewish men and organising mass executions – shooting them into pits.

From August 15, Heydrich extended the killing order to include women and children. Massacres multiplied in the countryside, on the outskirts of towns and in the camps.

Within a few months, nearly 500,000 Jews had been murdered.

In October, deportations of Jews from the Alte Reich – Germany, Austria, the Bohemia-Moravia protectorate – to the East began. From March 1942 onwards, gas chambers were put into operation in the extermination camps in Poland and Belarus. Spring was also the beginning of the Holocaust in Western Europe, from where deportations to the death camps began.

In the East, countries allied with the Reich, such as Romania and Slovakia, handed over their Jews and participated in massacres.

In occupied Greece, the Nazis struck at the heart of Jewish culture in Thessaloniki, which lost 98 per cent of its Jewish population. At the same time, the racial madness of the Reich also took between 220,000 and 500,000 Roma and Sinti, people the Nazis referred to as “gypsies”.

As promised at Wannsee, Europe was “combed from west to east”. In total, almost six million Jews, the majority in the East, were exterminated by the Nazis, with the help of their local allies and collaborators, particularly active and murderous in the Baltic States, Croatia, Ukraine and Romania but also in Western Europe.

The criminal dimension of the Holocaust is so monstrous and elusive that it continues to haunt Germany, Europe and countless Jewish families around the world. There is one particular aspect that troubles me. If populations had protested, would the Holocaust have happened?

My two first-hand witnesses, my father and his elder sister, disagree on this point. Whenever I interviewed her for my book, my aunt always defended my grandfather saying: “We can’t put ourselves in the shoes of people who lived in an era we didn’t experience, my parents lived under a dictatorship, to resist you had to be a hero.”

My father had a different view: “I used to tell my parents: ‘What bothers me is not that you gave the Nazi salute, because, perhaps I would have done the same, out of enthusiasm or cowardice. What bothers me is that even after the proof that this regime committed the worst crimes imaginable, you still won’t condemn it clearly and refuse to reflect on your responsibility’.”

It took me some time to understand that their divergence is also tied to the fact that my aunt was born seven years before my father, in 1936. She consciously lived the terror of the bombardments, the flight to the countryside and the traumatic return to a devastated city, peopled by starving, wandering ghosts, while my father experienced adolescence during the German economic boom.

She was also marked by the omnipresent Nazi propaganda and by the situation with Julius Löbmann, which, as a young woman, she perceived, through the filter of daughterly love, as an injustice to her family. Emotions and experience filter their memory. Testimonies have to be woven together with historical facts.

The Nazi regime was two-pronged. On the one side, it deployed seduction

and propaganda to solicit undying admiration and loyalty. On the other, it used a fierce system of repression to create fear and discourage dissidence.

During the war, as the Reich began to weaken, a terrifying atmosphere of paranoia and denunciation emerged, 16 000 German citizens were condemned to death, often merely because they had stolen a few chickens – defined as sabotage – or made a defeatist remark.

But before the war, there was more room to manoeuvre.

Belonging to a Nazi organisation was not obligatory, not giving the Hitler salute had few consequences unless you were a public figure, refusing to take over the job of a Jewish colleague was easy and it was possible to avoid buying Jewish businesses at knockdown prices.

But the Germans played the game step-by-step at a time when it might still have been possible to stop the infernal killing machine. Hitler regularly took the measure of his people to see how far he could go. For example, in 1941, in the face of Church and public indignation, he brought a halt to Aktion T4, the planned extermination of physically or mentally handicapped people, or those judged as such.

I often ask myself what I would have done. I’ll never know. But I understood what matters when German historian Norbert Frei noted that, if we cannot know what we would have done, it “does not mean that we do not know how we should have behaved”. And should behave today.

After the war, my grandfather received a letter from Julius Löbmann, once the part-owner of his oil company, now the only survivor of a family who perished in Auschwitz.

Julius demanded reparations. He argued that my grandfather had paid only for the material goods of his business – the property and equipment – and had given nothing for business goodwill; years of contacts and customers. It was a typical ruse of how the Nazi authorities drove down the sale prices of Jewish businesses. Julius asked for 11,000 marks.

In his letters, of which he kept a copy, my grandfather shows only denial and self-pity. But after five years of struggle, German justice forced him to pay.

In 1952, having originally offered only 4,000 marks, he handed over twice that much to Julius Löbmann.

It was, in those days, a considerable sum of money; around a quarter of the value of a small block of six flats that he owned in Mannheim.

My father also thought it was probably more than the value of the company at that time, but said, “In Julius Löbmann’s place I would have done the same thing.”

Julius had lost his wife, his son, his brother, all his goods and his country in the Holocaust. My grandfather was also paying for that and for the crimes of the Third Reich.

Mannheim, in the zone of Germany run by America immediately after the war, was more strict about reparations than other parts of the country.

As he watched some of the bloodiest criminals and the worst crooks and profiteers of the Third Reich profit by waves of pardons after the war, my grandfather felt like a victim.

Many Germans also claimed to have been conned by a bunch of criminal Nazi leaders. An event such as the Wannsee Conference had the advantage of corroborating this thesis of a top-down conspiracy, carried out in total ignorance of civilians.

As a teenager in the late 1950s, my father started to confront his father about the past and they often argued. It took the courage of my father’s generation to pull German society out of amnesia and make it face up to its responsibilities for the Nazi crimes.

This painful but necessary break is what allowed Germany to build its strong democracy – not on forgetting but on remembering the crucial role of the mitläufer.

Mitläufertum, following the current out of opportunism, indifference and conformism, is not an exclusively German phenomenon; it characterises the attitude of most European populations during the Second World War, with the notable exception of the Danish and Bulgarian citizens, who protected their Jewish population, and of the brave resistance movements.

After the end of the war, one copy of the protocol of the Wannsee conference was found in a castle in Marburg and viewed, but too late to use in the first Nuremberg trial against 24 major war criminals. It was used as evidence in

following trials.

But it took more than three decades for the international community to have the courage to face up to the sprawling dimension of the Holocaust and the multiple complicities that had made it possible.

Surprisingly, it was an American television series that opened repression’s floodgates, Holocaust by Marvin J. Chomsky and Gerald Green (from his own book), broadcast in the United States in 1978 then in Western Europe. The story of the Weiss family, who fall victim to the Holocaust one after another, suddenly made the unimaginable imaginable to the general public and unleashed an upheaval of collective conscience.

Survivors of the Holocaust emerged from oblivion and recording their stories became a top priority.

By that time my grandfather was gone.

He continued to operate the oil company until he died in 1969, but he was not a good businessman and by the end he had only a couple of employees left. My grandmother followed him 10 years later, taking her own life.

My father, not on good terms with his dad, did not go into the family business. He died in 2020, having seen my book about our family history in Nazi Germany published and translated into 12 languages.

Today, now that the last witnesses are dying, how can the memories of the Nazis, the war, Wannsee and the acts of ordinary Germans be passed on to younger generations?

By facing up to the shadows of history in a culture of responsibility, not in a culture of guilt. By showing that keeping memory alive is not a moral accessory to look good, but a precious guide to understand today’s world better and identify dangers that threaten what we cherish.

By reflecting on how the past can help us become aware of the consequences of our behaviour as citizens, voters and consumers. And inspire us to stand up for our values.

Géraldine Schwarz is a German-French writer and the author of Those Who Forget, My Family’s Story in Nazi Europe – a Memoir, a History, a Warning.