Drive through the Damascus suburb of Jobar, a focus of the anti-Assad regime resistance for a decade, and you wouldn’t imagine it possible to have survived here at all. Many lived here besieged amid fierce fighting, indiscriminate regime strikes, and chemical attacks. Now, there is silence – but if you stop the car and stand still for 10 minutes you will hear the sounds of life – a generator, a cockerel or a motorbike.

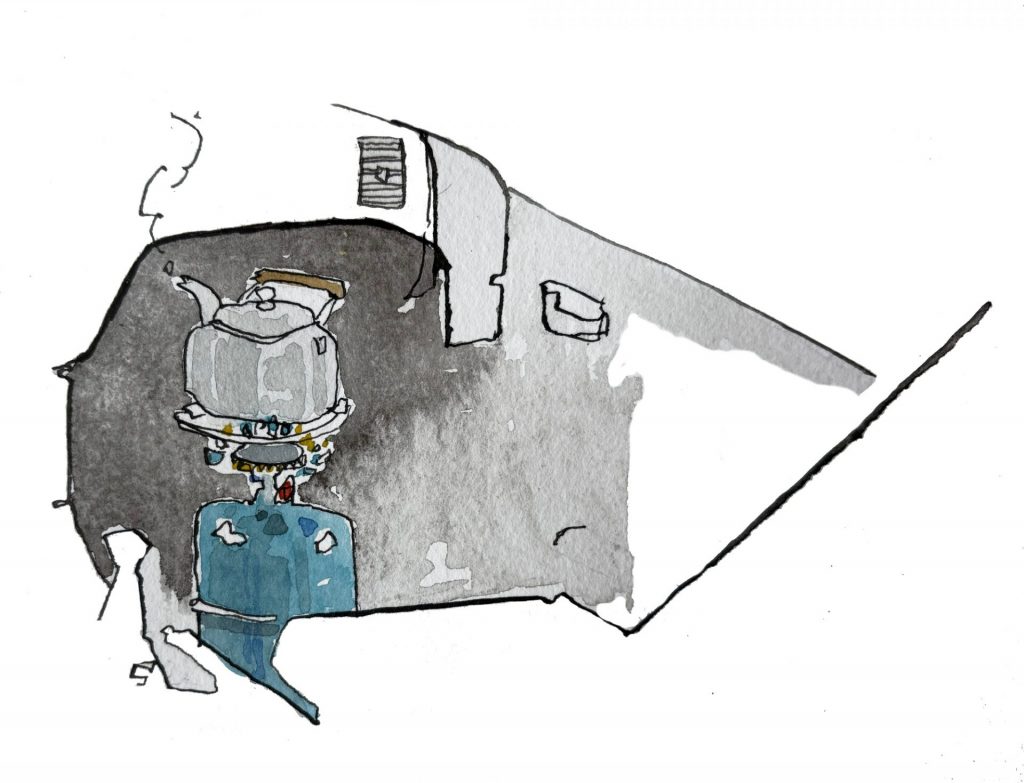

I found a car ticking over – and in it – two brothers. In the footwell of the passenger seat, they boiled a kettle on the top of a large gas burner, naked flame flapping. They led me through the destruction to a frenetic scene.

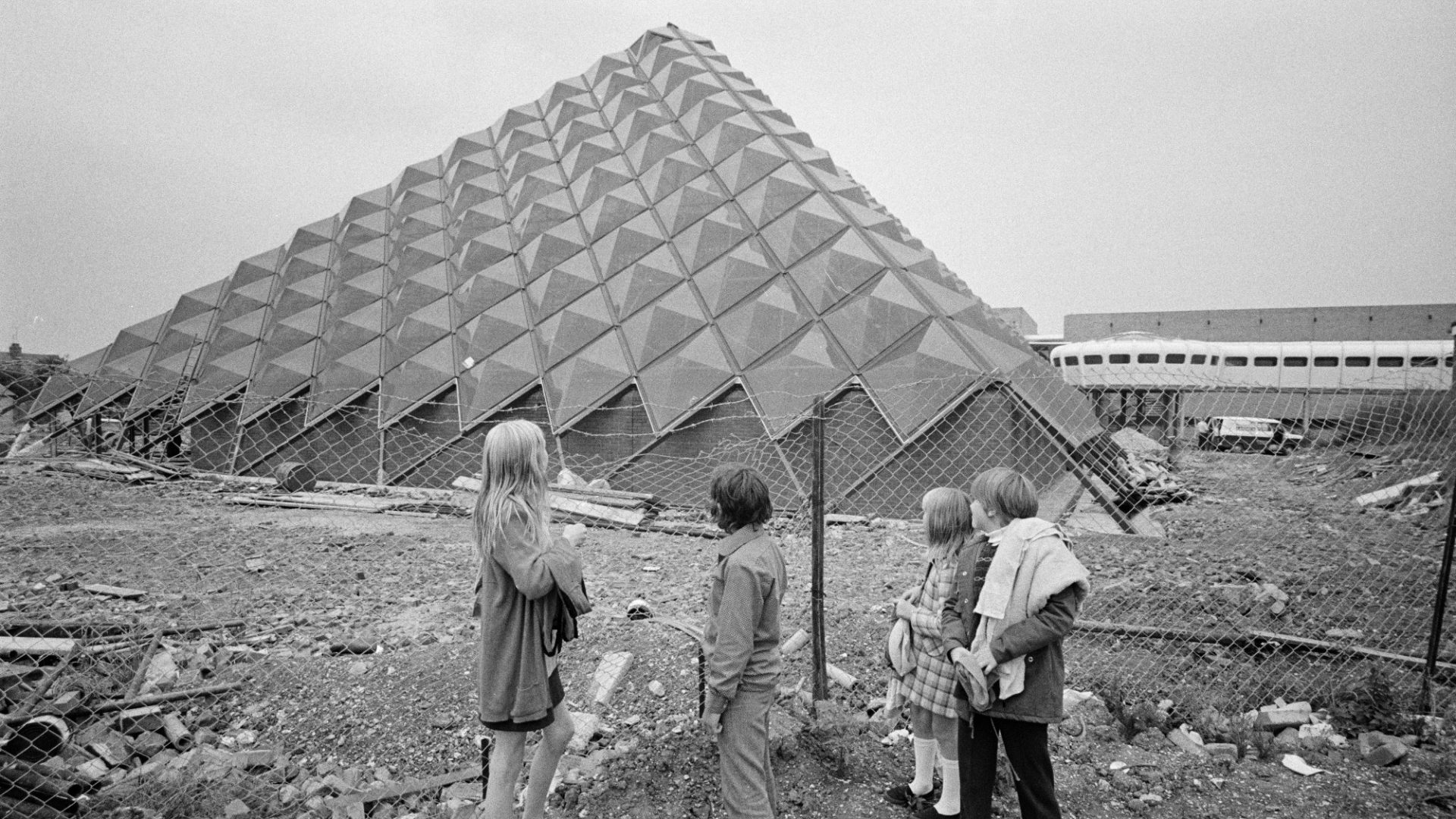

Freshly dug sand mapped well-trodden routes between the buildings. It looked like an archaeological dig. In fact it was what they call here a “gold mine” – one of the artisanal, makeshift pits that have sprung up all across Syria in an attempt to recover gold, ancient artefacts and jewels buried years or centuries before by forefathers, looters and invaders from previous civilisations.

During the Assad regime, this practice was forbidden to protect heritage. Now, in some areas of the country, ancient antiquities are under threat as landowners dig up anything they can find to supplement their incomes. Some, understandably, see it as their right having lost so much.

At one extreme it is organised criminals raiding ancient treasures and smuggling them out of the country. Here in Jobar it’s not, they only dig under their homes.

It’s not gold digging as I imagined; There’s no panning through the sand or chemical extraction: there’s no map or metal detectors, or surveys, this is more of a treasure hunt under the ruins of the bombed-out Sunni neighbourhood. In truth, there is very little evidence of treasure or bullion being buried in Jobar at all. It’s speculation in every sense of the word.

Stories online from Daraa to the banks of the Euphrates report life-changing finds. But hearsay drives this on, and in response, many have hired equipment, sold their homes, taken out loans and begun the search. None of those I spoke to have found anything… yet.

I met Sardar, in his early thirties. Like many, he believes the Jews that lived here “2,000 years ago” buried gold under their homes. To keep up morale, Sardar flicked through photos on his phone of Byzantine coins, or gold-leafed Jewish texts, which had apparently been found nearby. Tonight Sardar and his friends would sleep in their cars in case anyone came to steal their bounty.

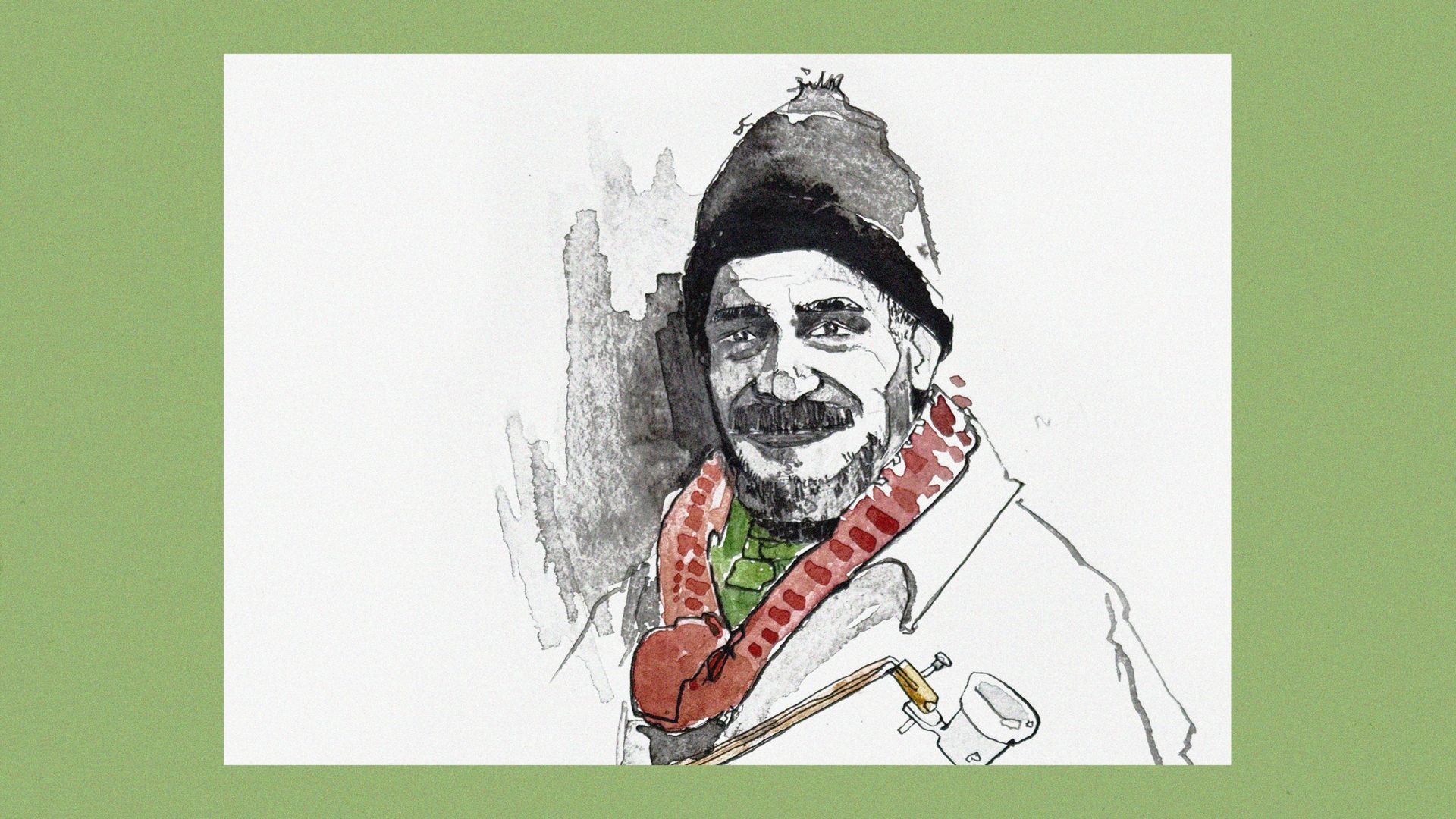

On site I found Abu Mohamad, nearly 50, a self-described “finder of buried items”. He was holding a brass-handled contraption and he used this to search the rubble in front of him.

He tells me: “I have been doing this for 20 years, you need a lot of experience, because the machine works through the blood, and the machine works for you only… five times I have found gold.”

Abu Mohamad says he served three and a half years in Intelligence Branch 227 and Adra prison for digging up ancient artefacts. “The regime put me in the jail because I was doing this job, then I stopped, and now that the regime has gone I have started again,” he said with a grin. Business was good, his assistant Bilal confirmed.

Ibrahim stumbled around in the rubble holding the wedding ring of a bystander next to the contraption – like showing a sniffer dog a piece of clothing of the fugitive before setting it off on the trail. As others watched and waited eagerly, he returned with bad news… “no gold here”. That didn’t put anyone off.

The work is extremely dangerous. However danger in Jobar is relative to the last decade, where life could be extinguished without thought. Several of the men wear plaster casts, and this month three others have been reported killed in Al Sehel, 85km north of Damascus. Those in search of treasure with metal detectors often find mines instead.

“If you bought a machine from England for $13,000, we would split the rewards with you and you’d make far more than you do as a journalist!” said Sardar.

Even with Syria’s Ottoman, Byzantine and Roman heritage and some sectarian customs of burying wealth with the deceased, the chances in Jobar are infinitesimally minute.

I found another site next to the ancient synagogue Eliyahu Hanavi, built in 730BC and destroyed in 2014. Abu Shadi showed me his home. It is now just a messy concrete floorplan, but he gently – heartbreakingly – showed me around as if the walls still stood.

Under what used to be the kitchen there was a seemingly bottomless excavation out of which with the use of two stepladders appeared three men – covered in dust.

A battery-powered LED strip light lit the cave, and a man hacked away with an inadequate pickaxe. For a moment, I felt as if I was playing along with a charade, where maybe we all knew it was futile but if the mystery was unveiled then the uncertain and painful reality of life would have to be faced back at the surface.

Around the corner in the shadow of the destroyed Jobar mosque, brothers Rabbi, 53, and Abdul Karim, 70, dug to find their grandfather’s treasures. “We are digging for gold here,” Rabbi announced. “Our grandfathers told us that there is gold here. This method is 5,000 years old… Our grandfathers put it here, but we cannot find it… just stones.

Their house had been hit by a missile in 2012, and only two walls remained. At the bottom of which they had dug another gigantic pit. This was a more professional outfit, a generator was on hand to power a handheld pneumatic drill. Freelance workmen had been hired. But it had still taken seven men two weeks, working in shifts.

“We will dig for another week,” said Rabbi.

In Syria, 90% of people live below the poverty line. The country will cost an estimated $500bn to rebuild. The treasure hunting illustrates the desperation of many and the struggle that they face, even after the fall of the regime, to make ends meet.

It is the behaviour of those who have been betrayed, killed, disappeared and robbed by their own government, those who stand on their destroyed houses, those who have tiny monthly salaries and large numbers of dependants. Those who don’t know what tomorrow brings.

In some cases it’s less painful to keep looking with a chance at striking gold than to accept that life had been taken by the regime. It was desperate work.

Over the day I realised treasure wasn’t the only purpose to this pursuit. For many like Rabbi and Abdul Karim, this was the first time they had been back to their homes for a decade.

They were allowed to sit at home, with their families, the kettle on – constantly, the free Syrian sun shone. They had survived. They told stories and remembered their loved ones. They speculated on the future.

They were in control of their small patch of land for the first time in a lifetime. Whatever they found or even if they didn’t, this marked the end of one time and the beginning of another.

George Butler is an award-winning artist and illustrator. His work in Syria is funded by the Pulitzer Center.