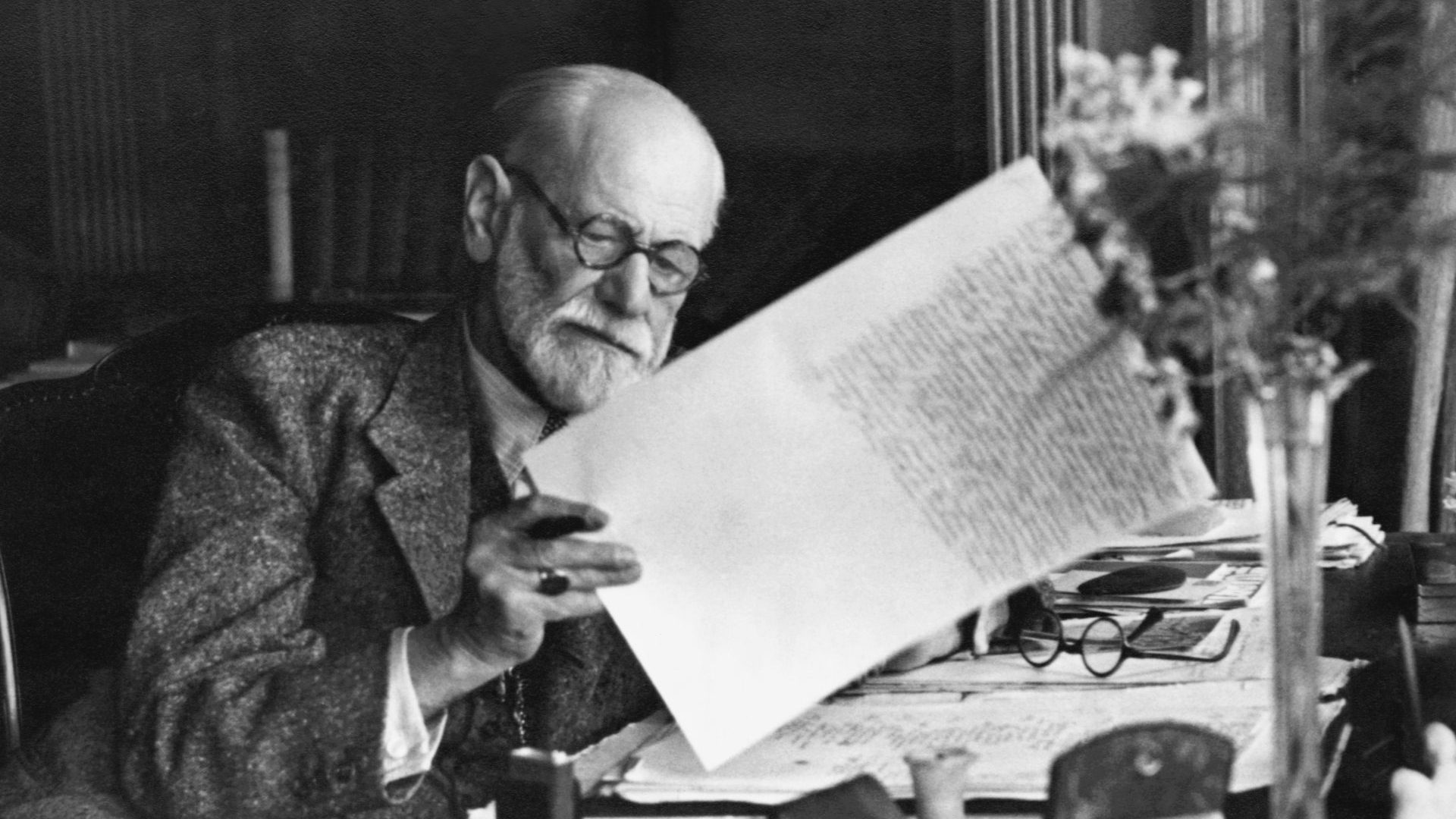

As the father of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud is seen as the cool, dispassionate master of human emotions, but that didn’t stop him from ranting about Americans, freshly translated documents show.

The Austrian complained that people in the US weren’t as bright as Europeans and were impatient. He made no secret of the fact that he was “insulting” the US, a country where his teachings would go on to be highly influential: it can sometimes seem as though every other New Yorker or Californian is seeing a shrink.

Freud (1856-1939) revolutionised understanding of the mind and mental illness at his practice in Vienna. It is 100 years since a British publisher, the Hogarth Press, brought out his canonical works in English, and the 50th anniversary of them all appearing in the language together for the first time. They are published in an updated version this month in no fewer than 24 volumes running to 8,000 pages – and they’ll set you back £1,500.

The old boy is having a bit of a moment: Sir Anthony Hopkins stars as the eminent doctor in a new film, Freud’s Last Session.

Freud’s tirade about Americans was cut out of one of his books and went undiscovered for decades, but is being included in the definitive version of his texts by his latest translator, Mark Solms. “You’ve never read anything like it. It’s the most rabid attack on American culture and mores,” says Solms, who is a psychoanalyst himself and based at the University of Cape Town. He has spent 30 years on the mammoth task of revising the standard English version of the doctor’s works.

Freud travelled to the US in 1909 and pronounced himself impressed, particularly by the emphasis on liberty and equality he found in American culture. However, he came to see Americans as puritanical about sex, and disliked what he saw as the grasping competitiveness of US society. He was also upset that Americans addressed him as “Sigmund” instead of “Herr Doctor”. He is supposed to have told a friend, “America is a mistake; a gigantic mistake it is true, but nonetheless a mistake.”

He unburdened himself of his thoughts on Americans in his book The Question of Lay Analysis (1926), but they were struck out before publication. He believed that lay people – who weren’t medically qualified – were capable of training as psychoanalysts, but many in the US disagreed, perhaps fearing that this would encourage quacks. In an unpublished section of the book’s postscript, Freud retorted that America was simply not ready to match Europe in this field. He said: “It is indisputable that the level of general education and of intellectual receptiveness is far lower than in Europe, even in people who have attended an American college.” He noted of go-getting US society: “the American never has enough time”.

Freud criticised would-be patients of psychoanalysts for not taking enough care to find a good practitioner. “I cannot say what feature of the American mentality is to blame for this, and how it happens that people – whose highest ideal is after all ‘efficiency’… – fail to take the simplest precautions when seeking help for their mental troubles.” He grumbled that there was no institution to train psychoanalysts “in wealthy America, where money is readily available for every extravagance”. In Freud’s judgement, the hapless analysts of the US weren’t even capable of getting up to speed by studying the literature on the subject. “The good books in English are after all too difficult for them, and the German ones are inaccessible,” he said.

Perhaps wisely, Freud instructed a colleague to “omit some sharp remarks about the Americans if he found them not politic or dangerous”. The comments were duly excised and weren’t published until almost 70 years after The Question of Lay Analysis first appeared.

Until now, the definitive version of Freud’s works in English was a translation made in the 1950s and 60s by a man named James Strachey. Solms, 62, says he has corrected some errors. “Strachey was elderly, and his sight was poor. I’ve also changed some technical terms that are outdated now, and I’ve added essays, lectures and other writings that weren’t in Strachey’s version.” In the updated works, “subtle underlining” points out Solms’s variations: his revisions and additions.

He was perhaps uniquely qualified for the task of grappling with Freud’s original writing. He was born and raised in the former German colony of Namibia, where some people still speak an antiquated version of German that was heard in the coffee houses of 19th-century Vienna. Despite this, Solms modestly declined to attempt his own version of the historic opus, opting to follow in Strachey’s footsteps instead. He said, “I would only replace it with an equally imperfect translation, if not more imperfect.” Besides, Strachey was a “master of the English language” and knew Freud well, he added.

Despite that, demand has been growing for “a new Freud” since as long ago as the 1980s. Solms says: “People were screaming for a different translation to Strachey’s. It wasn’t a matter of the translation itself. One of the main criticisms of Strachey is that he falsely scientised Freud, so to speak. In other words, he made him sound much more of a scientist than he was.” In matters of the mind, Freud believed that how we feel is at least as important as what our brain chemicals are actually doing.

His ideas made him enemies in his own time. His revolutionary theories about the Oedipus complex, the meaning of dreams and more were offensive to conservatives and the religiously inclined. The new movie, Freud’s Last Session, depicts an imaginary encounter between Freud, an atheist, and CS Lewis, the author of the Narnia stories who also wrote influential books about his Christian faith. In interviews, Hopkins has suggested that the film-makers may be more interested in this clash of ideas than audiences. He said: “The problem is that everybody gets over-concerned about everything – everything has to have a message. But nobody gives a hoot about what Freud thought. Nobody has even heard of him. We’re too busy living and dying, and who cares?!”

Solms agrees that many would be entirely sanguine to see Freud’s ideas disappear: a lot of the current medical profession, for a start. “There are people who would rather see Freud forgotten than retranslated. They would prefer it if he was airbrushed out of history,” he says.

Freud’s practice was to start with the life experience of his patients. “He believed that the mind was subjective, but after he died, we pivoted towards something called behaviourism. In other words, you cannot study the subjective mind but [must study] objective factors instead, such as behaviours,” says Solms. Freud advocated talking cures, but in modern psychiatry, “we don’t treat the mind mentally but pharmacologically”.

However, Freud is coming back into fashion, according to his latest translator. “There’s growing public awareness that linking depression to a chemical imbalance in the brain is a questionable approach to mental illness.”

Freud is almost a victim of his own success, says Solms. “Many of his ideas are so taken for granted that we forget he had them first: for instance, that what happens to you in life – especially in the early years – affects the rest of your life. In other words, it’s not just about your genetic blueprint.” Other notions that we accept as “truisms” have also come down to us from Freud’s consulting room, according to Solms. “The idea that we are not transparent to ourselves, that we are unconscious of many of our drives, and that your early experience of your caregivers leaves a deep imprint on you for the rest of your life: these are all Freud.”

Despite the good doctor’s reservations about the US, Solms has unearthed evidence that he took the trouble to make a case study of the most eminent American of them all: the president himself. This revelation will be seized upon by Freud scholars, who have long debated whether their hero did indeed put the leader of the free world on the metaphorical couch. A man called William Bullitt published a “psychobiography” of Woodrow Wilson, who was in the White House from 1913 to 1921. It appeared after Freud’s death, but Bullitt claimed that Freud was his co-author. Freud’s daughter disputed this, saying that her father had never met the president and without meeting him wouldn’t have offered any view of his mental health. But in Yale University library, Solms uncovered an original manuscript of the first two chapters of the Wilson book – in Freud’s handwriting. “It’s the smoking gun of Freudian studies,” he laughs.

The revised standard edition of Freud’s works was commissioned by the Institute of Psychoanalysis and is published by Rowman & Littlefield.

Stephen Smith is a writer and broadcaster