“Liberty is meaningless,” declared the great Black abolitionist Frederick Douglass in 1860, “where the right to utter one’s thoughts and opinions has ceased to exist. That of all rights is the dread of tyrants. It is the right which they first of all strike down. They know its power.”

When did this statement of fundamental principle cease to be a core western orthodoxy? When did freedom of speech lose its prime position in the hierarchy of moral and political values?

This question struck me vividly on Friday when Maya Forstater, the tax expert and feminist campaigner, finally received the justice for which she has been fighting since 2019. In that year, her contract with the thinktank, the Centre for Global Development, was not renewed, after she posted a series of tweets asserting (for example) that “[a] man’s internal feeling that he is a woman has no basis in material reality” and that “male people are not women”.

In June 2021, the High Court ruled that her views on the “immutability of sex” are a “philosophical belief” protected by equality legislation. Last week, a tribunal of three judges awarded Forstater more than £100,000 in damages.

My first job in journalism, in 1991, was at the free speech magazine, Index on Censorship. At that time, the defence of free expression was overwhelmingly led by progressives; no surprise, given the geopolitical backdrop: the end of the cold war, the collapse of apartheid, and the Rushdie affair.

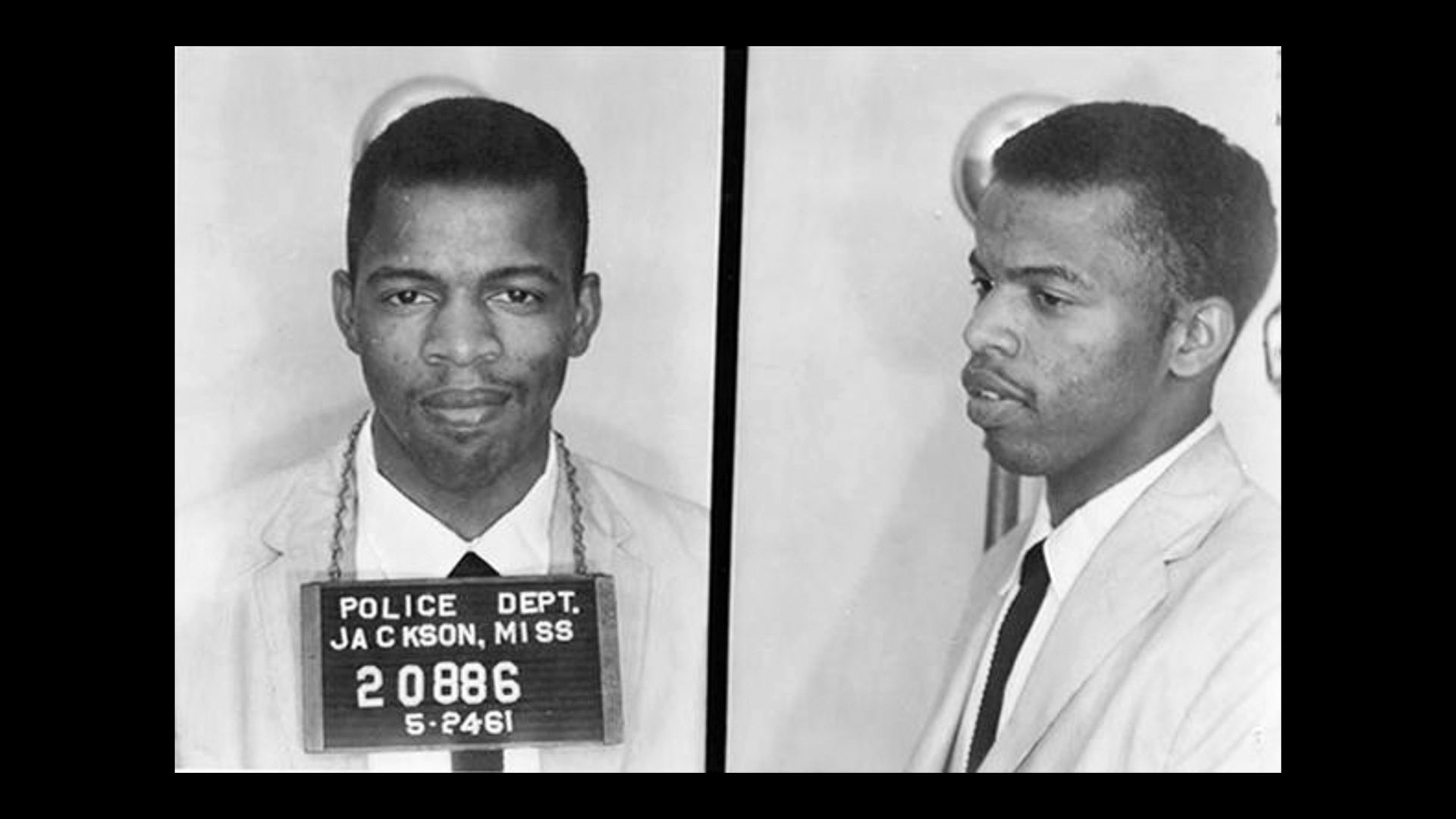

This alliance between free speech activism and the liberal left had deep roots. In the 20th century, WEB Du Bois, Martin Luther King, and congressman John Lewis had recognised that, for minorities and the disenfranchised, free expression was the first line of defence.

“Without freedom of speech and the right to dissent,” said Lewis, “the civil rights movement would have been a bird without wings.” In the 1960s, the same was true of the Berkeley Free Speech Movement and its student leaders such as Mario Savio; and, in the 1980s, of eastern European dissidents such as Vaclav Havel who battled against the totalitarianism of the Soviet bloc.

In 2023, however, the political and social landscape is radically different. Polls show consistently that free speech is no longer a priority for young people, many of whom regard it with suspicion as an offshoot of male white privilege. Universities and employers often subordinate this previously cherished liberty to the claims of “offence” (necessarily subjective) and to the risk of “harms” (usually ill-defined).

One egregious outcome of this cultural shift is that an alarming number of people – especially gender-critical feminists – have lost their livelihoods. In October 2021, for instance, the philosophy professor Kathleen Stock was driven to resign from the University of Sussex by a campaign of intimidation that included the letting off of flares by masked trans activists outside her family’s home and the warning: “Fire Kathleen Stock. Otherwise you’ll see us around.”

The standard riposte is that Forstater, Stock and others like them (though by no means all) have gone on to other forms of gainful employment and prominence in public life. How, then, could they possibly have been “censored”? This is an absurd and infantile argument. The fact that these two women have been sufficiently resourceful and resilient to find new ways of making their ideas known and their voices heard is neither here nor there. Stock should never have been menaced to the point that it was intolerable for her to remain a faculty member; Forstater should not have lost her job.

So this was a good ruling. It will be harder for petition-drafters and online mobs to drive people from their workplaces. There will be less self-censorship. One of the most basic principles of a pluralistic, complex society has been reasserted.

Those who present themselves as enlightened gatekeepers at the checkpoint of acceptable speech – ensuring that what they regard as bad ideas are “deplatformed”, exiled, denied space in the public square – reveal only their spectacular naivety.

Because once you normalise censorship, everyone wants in on the act. Censorship of one sort nurtures censorship of all sorts; and it is a grave error to assume that the censors will always be on the side of the common good as you define it. As the American intellectual Jonathan Rauch argued in his prophetic book, Kindly Inquisitors (1993): “[W]hat about the day when right wingers get the upper hand? Will they be “fair”?… no one stays on top for long.”

Look at the crackdown on left wing academics that followed the election in 2018 of the populist right wing president of Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro.

Look at Viktor Orbán’s record of censorship since he became Hungary’s prime minister in 2010.

Look, above all, at what the US Republican presidential contender, Ron DeSantis, has been up to in Florida, with legislation that threatens teachers with felony indictment if they stray beyond what is now ideologically permissible.

Among the hundreds of books that have been removed from school shelves are Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five; Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye; Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things; and Jodi Picoult’s The Storyteller. Teachers in the sunshine state are increasingly fearful of teaching the historical truth about slavery.

All this was as predictable as it is monstrous. It reflects, of course, the political appetite of the right for culture wars. But it has been made much easier by the neglect of free speech as a precious progressive value; by the way in which those who fight for social justice have so often regarded this most basic liberty as dispensable.

In truth, it is the foundation of all other liberties. As Mario Savio put it in 1994, two years before his death: “To me, freedom of speech is something that represents the very dignity of what a human being is… That’s what marks us off from the stones and the stars.” That remains true today; which is why the Forstater ruling is good news for everyone.