France is attracting social media ire and international media fire after its decision to ban the abaya – the long Islamic dress – from public schools.

The critics – including the strange bedfellows of the Guardian, New York Times, Recep Erdoğan’s Turkish TRT network and propaganda channels operated by Iran’s mullahs – have portrayed the birthplace of Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité as a vector of Islamophobia, discrimination and “clothing police for girls”.

But are such portrayals accurate when they deal with what to its supporters is merely the reiteration of a core national value – laïcité, or secularism – anchored in the French revolution? Its practical application dates far back beyond the controversial 2004 legislation that kept the veil, the kippah, turbans and large crosses out of schools – right back to the 1905 law separating the Catholic church from the state, in fact.

A closer look at the debate – one that takes in polls of voters and teachers, and the voices of prominent French secular Muslims – suggests otherwise.

In contrast to social media noise and isolated protests by teachers, popular support for the measure announced by the new education minister, Gabriel Attal, for the back-to-school September rentrée appears to be overwhelming. According to an IFOP survey, the vast majority of French voters are in favour. Approval ratings are higher than for Jacques Chirac’s 2004 secularism law, enshrined after a concerted push by Islamic religious conservatives to impose the veil on young girls in a country that pre-1989 counted far fewer head-covered Muslim women.

Some 81% back the abaya decision, including 58% of far-left voters for Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s La France Insoumise (France Unbowed). This is awkward for Mélenchon, a Jeremy Corbyn ally, as he is against the ban. It is supported, however, by 79% of Green voters, 73% of Socialists and 63% of activist feminist voters. Among teachers and school staff, support is similarly high.

Critics at home and abroad tend to link the measure to the extreme-right galaxy of Marine Le Pen and Éric Zemmour. Yet prominent left wing figures have also stood up for the ban. Communist Party leader Fabien Roussel, who fought off a stiff challenge from Le Pen’s National Rally in France’s north during the 2022 election, said he approved of a “necessary” measure. Socialist MP Jérôme Guedj agreed.

It is true that the radical left has abandoned its previous unwavering support for laïcité in the country with Europe’s largest Muslim population, drawn mainly from former French colonial territories in north Africa and sub-Saharan Africa, but more recently from Turkey and south Asia.

National Assembly deputy Clémentine Autain of France Unbowed says the ban is “characteristic of an obsessional rejection of Muslims”, while her colleague Mathilde Panot claimed on Twitter: “Muslim girls are getting sent home from public schools for wearing… loose clothes.”

She added: “Abayas are a non-religious, cultural piece of clothing originated in the Middle East. The French principle of laïcité is used to justify the ban, although what is being observed throughout the country is Muslim girls being set aside and sent home for wearing loose clothes.

“They are being targeted and unsufferably questioned about their bodies and clothing.”

Kenneth Roth, the former long-time executive director of Human Rights Watch, agrees with Autain and Panot. “It is hard to see why France’s secular tradition is endangered just because a handful of girls choose to wear an abaya,” he wrote earlier this month. “Allowing them to dress as they want isn’t an endorsement, but banning the abaya looks like anti-Muslim discrimination.

“Many Muslim children are left behind in France, but instead of investing in their schools, French authorities are wasting time and resources banning abayas.”

According to political scientist Gilles Kepel, chair of Mediterranean and Middle East studies at École Normale Supérieure in Paris, the abaya, which means long dress in Arabic, came into fashion in Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states in the mid-20th century when women emerged from harems into public spaces. “Wearing the abaya is a Salafist injunction, not an Islamic commandment,” Kepel says, referring to the hardline Islamist fundamentalism that emerged from Saudi Wahhabism. “It is a religious garment by projection, by destination, like a health mask worn to conceal part of the face. Islam, like other religions, simply recommends modest dress. The Salafists want to impose their branding on French society so that they can take their fellow Muslims hostage.”

A sartorial analogy could be made with ultra-Orthodox Jewish clothing, or Amish clothing, as if such garments represented the mainstream of Judaism and Christianity, rather than hardline fundamentalist approaches.

As for French Muslim politicians, activists and intellectuals, there are plenty of dissenting voices. After Mélenchon declared the government had launched an “absurd religious war”, the new minister for cities, Marseille politician Sabrina Agresti-Roubache, retorted: “The great majority of French Muslims in our country, of which I am a part, refuse the instrumentalisation of our faith by Jean-Luc Mélenchon… we will apply the law and nothing but the law and take away the mental pressure on principals.”

Gay activist Mehdi Aifa, who grew up in the banlieues or suburbs and has been harassed for being homosexual by people citing the fact that his sexual orientation is forbidden by Islam, insists “the public school of the secular Republic does not have to adapt. No one is forcing parents to choose these schools,” he says. “Denominational schools exist… The 2004 law is not new: ‘The wearing of signs or clothing by which students ostensibly show a religious affiliation is prohibited’. To be surprised today is pure hypocrisy.”

Philosopher Razika Adnani, a reformist Muslim, wrote in Le Figaro that the abaya was a sign of rising fundamentalism and radicalism and even more in keeping with the Koran than the foulard or headscarf. As TikTok viral videos seem to confirm, she says it is mostly worn by girls who take off their headscarves at the doors of schools and want to distinguish themselves from their fellow students, both Muslim and non-Muslim.

“Even the use of the term abaya reveals the desire of French women of Muslim confession to resemble Saudi women in the way they wear the veil, given that it is the term used in the Arab peninsula to designate a long and ample dress that women but also men wear. In the Maghreb the term gandoura is used,” Adnani said.

Francophone intellectuals such as the award-winning Algerian novelist Kamel Daoud have been scathing, recalling the bloody war in Algeria in the 1990s against Islamists, who forced women to cover up, and the fact that the abaya is not permitted today in his home country.

“France is being played out in its schools and its teachers are its lonely trench,” Daoud wrote in Le Point. “And it’s worth remembering that Islamism in the Maghreb began in schools and that Taliban means ‘students’. Make no mistake: this is a deliberate, voluntary act, finely concocted to lead to reactions that range from the media counter-charge to energetic contrition, from the self-flagellation of the elite heirs of guilt to the anger that claims to be holy. What is wanted, among the inventors of this controversy, is to maintain the staging of an Islamophobic France whenever this country tries to free itself from the trap that closes in on it.”

Emmanuel Macron has explained the abaya decision in several interviews, making specific reference to the beheading of teacher Samuel Paty almost two years ago in front of a middle high school outside Paris by an Islamist terrorist, after he showed Charlie Hebdo caricatures of Muhammad in class. The French state would be “uncompromising” in defending laicité in schools and was considering “experimenting” with school uniforms, the president said.

Since Paty’s murder, breaches of secularism rules have rocketed in French schools, leaving principals and teachers in the difficult position of having to deal with them on a case-by-case basis. Now the state has stepped up and offered clarity – albeit clarity that is guaranteed to bring conflict.

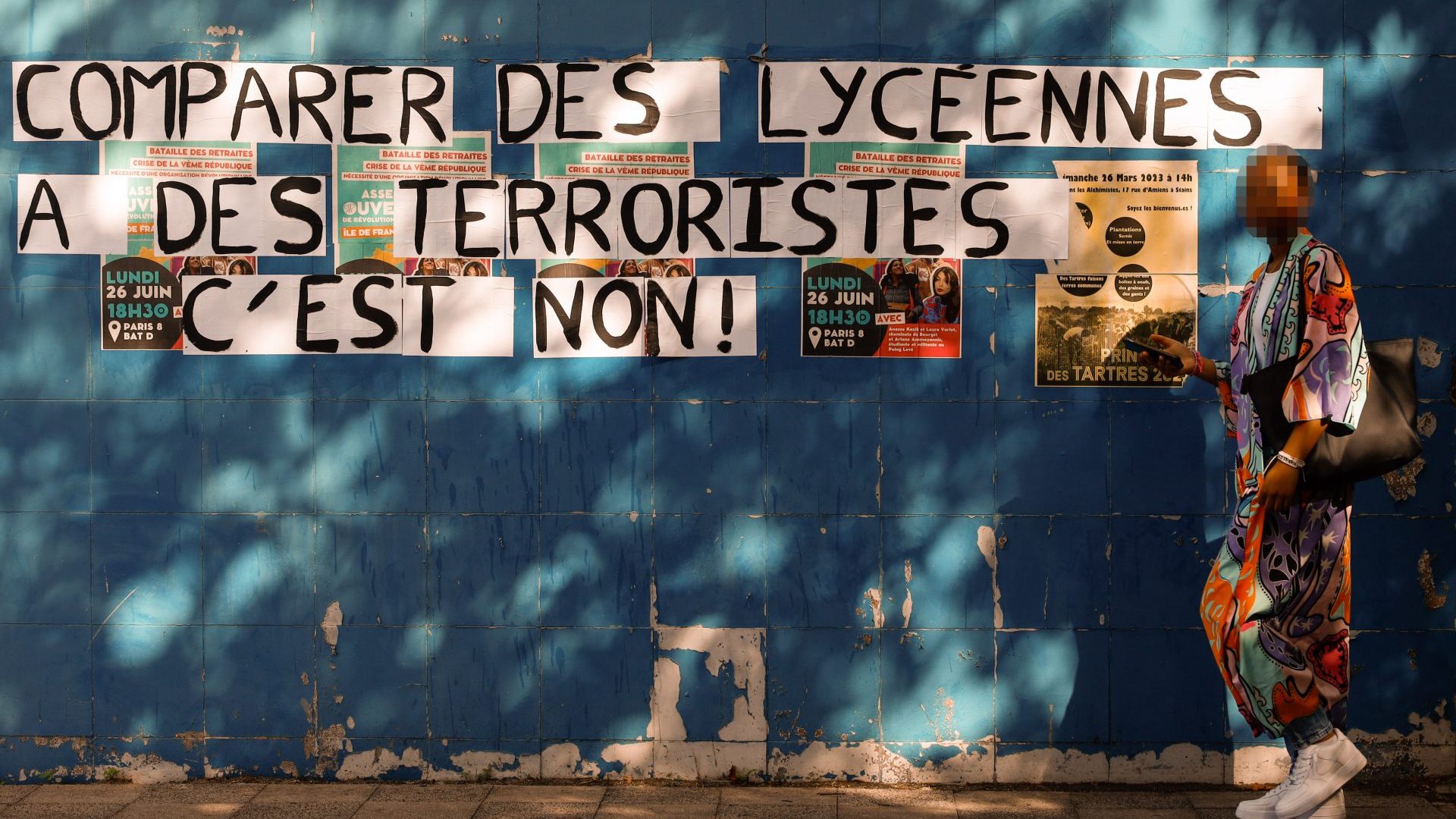

But perhaps less conflict than anticipated. In protests after the implementation of the measure, no girls were expelled from school but 67 were sent home, a rather small number considering how many students are enrolled in French schools (12 million). Only small protests were held in neighbourhoods outside Paris, reclaiming the abaya as Muslim religious dress, driven by fringe groups like the decolonial separatist Parti des Indigènes de la République, with support from Kremlin-backed media like Sputnik.

The father of a public high school student in central France was taken into police detention for making death threats against the principal and staff. But his daughter was the only student of 1,300 who flouted the rule.

As the weekly newspaper Franc-Tireur reported, many teachers have noticed the visible progression of the abaya in recent years. “Opponents of the abaya ban should move out of their hypocrisy and assume their rejection of the 2004 secularism law. If they want to ban the ban on the abaya, what will they say about the veil, whose religious character some students also strategically deny? If the judges follow, that will simply mean 20 years of struggle to protect the secular school goes up in smoke,” it said.

To the relief of the government, the Conseil d’État, France’s highest administrative court, upheld the ban on September 7, rejecting an appeal by a Muslim association. The wearing of the abaya (or the male equivalent) “is part of a logic of religious affirmation”, the judges wrote, and its prohibition “does not seriously and manifestly unlawfully infringe the right to respect for private life, freedom of religion, the right to education, respect for the best interests of the child or the principle of non-discrimination”. So far, there is no sign of appeal to a higher court.

France has made its decision. The question now is whether any neighbouring European countries will dare to do the same.