“Visa wizard – French visas”. “How to get French citizenship”. “Cheap French masters in English”. “Can I pay a French citizen to marry me?”. My search history, summer 2023.

Burnt out and disorientated after four years of university, there was only one thing on my mind. No prizes for guessing.

I’m not a Francophile. I don’t like sauces full of butter, red wine is something I drink to be polite, and the genius of the Nouvelle Vague movement never grabbed me.

I wanted to move to France for two reasons. The first: maybe I could stay long enough to qualify for citizenship, and later an EU passport. The second: I had learned French at school, and it was the only modern language in which I could become vaguely fluent any time soon.

It took until late November to work out how to progress. Out of pocket after completing a TEFL course (Teaching English as a Foreign Language) only to discover that no French language schools offered positions without a prearranged right to work in the EU, I Googled my nights away.

The weeks dragged on. I grew to resemble Camus’s post-crisis Clamence from The Fall, raving and sobbing my way through the claustrophobia of a post-Brexit Britain.

Then it happened – my coup de foudre came via the gouvernement français website: the “Young Au Pair Visa”. Requirements: aged 18-26, proof of some level of French education, employment agreement with a host family.

Tick, tick… I bashed out a profile on Aupairworld, forgetting I’d promised never to au pair again. By the morning, five families had asked me to come and teach English to their children.

Video interviews proved a two-way vetting process. I chatted to parents, with variable grammatical success, viewed prospective bedrooms (some of which had doors), and tried to get the measure of bouncing children.

Parents were either aloof, nervous, or suspicious of my British status. I explained to one couple that French law required them to pay my health insurance. They ceased contact, believing this was a direct result of my non-EU status.

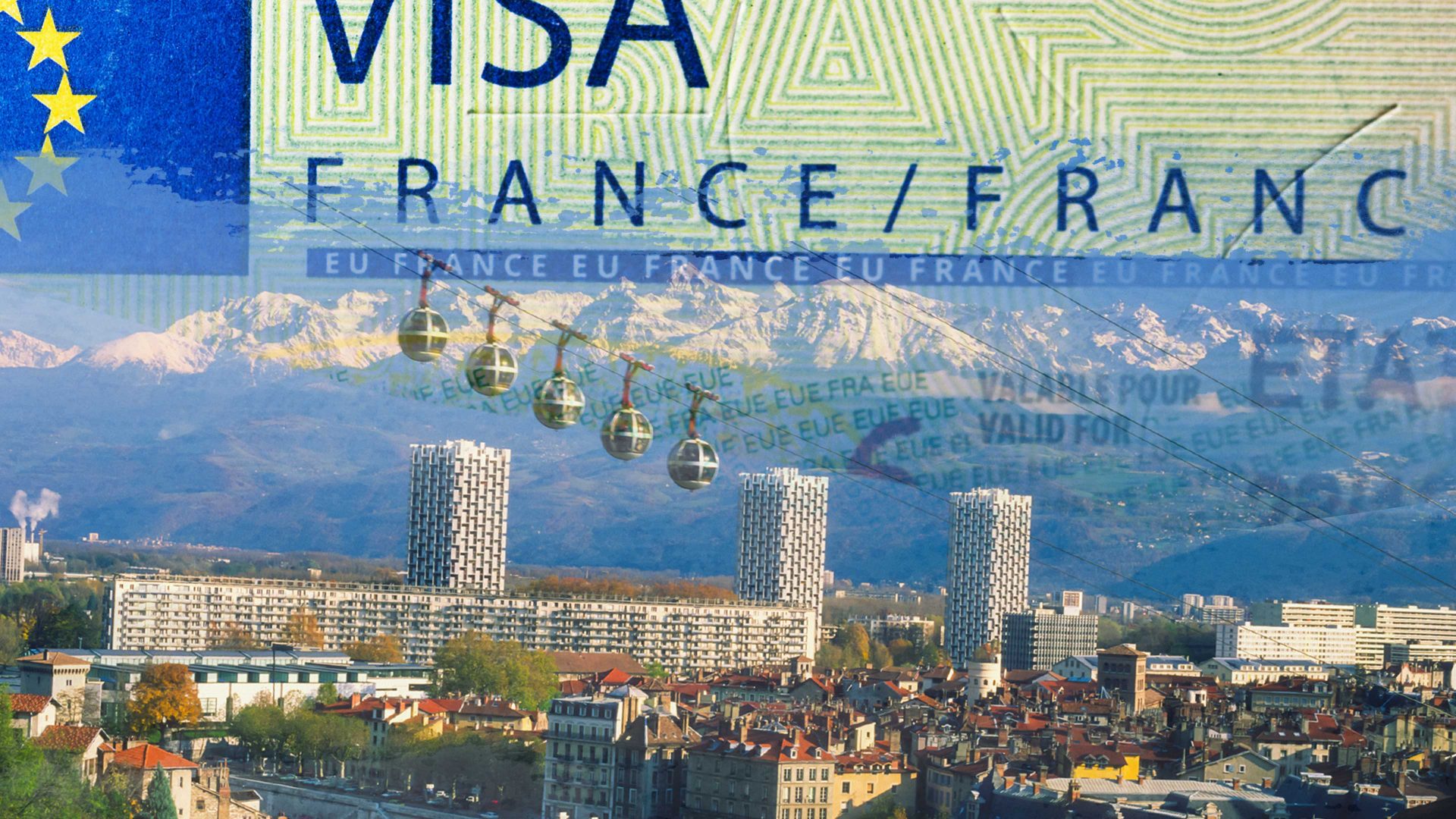

I picked a family. The exuberant young boys had giggled and yowled throughout the call from their sunny kitchen on the outskirts of Grenoble. The parents have professional jobs, but they are normal people living in a modest new build.

“If the dinner gets cooked and the bins are emptied, that’s a bonus,” said Maëlle in a fit of generosity, “but what is most important is that we have someone whom the boys will love, who will speak to them in English.”

Three months on and I remain grateful for the post. As far as foreign exchanges go, I got the best one. Language barriers prevented me noticing when the family tucked into steak tartare au cheval, but I speak French every day and have the best guides to local culture in my living room. I know my neighbours. I shop in a greengrocer’s that sells tomatoes like rubies. I wake up to sunlight on the mountains.

That said, the pay is bad, and there are times when I feel I’m back living with my parents again. Still, I’m lucky. For reasons too thorny to cover, most families search for English-speaking women to care for their children, leaving male language learners in a difficult position.

In the absence of any other easily accessible visa, I have no advice for them. Doubtless, later generations will profit from the arrival of working holiday visas, but for now, those of us too young to have voted in 2016 are in a bit of a jam.

In Grenoble, I take a French class for immigrants at the local university. We’re a mixed bunch: Ukrainians, Americans, Germans, Colombians, Turks, it goes on. I am the only Brit.

A high point came when I travelled to Lausanne to meet a university friend. Patterned roofs and the glittering waters of Lac Leman were not yet in view when I reached the gritty suburban coach station.

Shared confusion caused by an impenetrable ticket app forged an alliance with a Swiss student of my age. We chatted for 30 minutes, without my usual floundering. She asked if I was German. “No,” I said, “I’m from the UK.”

She pursed her lips: “Where’s that?”

Isabella Redmayne is a recent graduate. Her fiction has most recently been published by t’ART Press