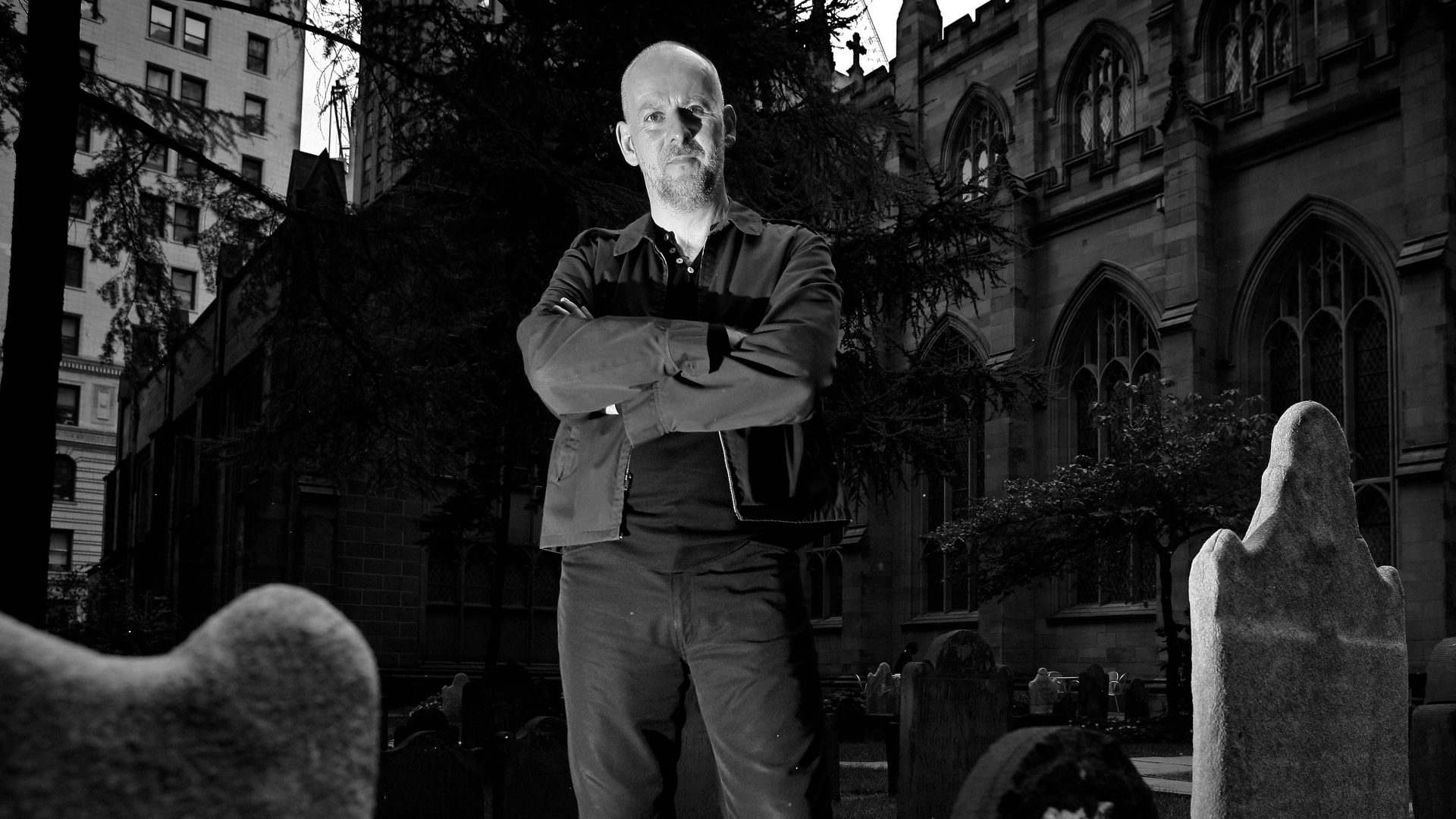

How should we understand reality in a digital age? The popular acronym “IRL”, short for “in real life,” contrasts real life with digital life. On social media, I post photos of philosophy conferences. In virtual reality, I’m a whiz at playing the rhythm game Beat Saber. But IRL, I’m a professor at New York University who writes books about consciousness and reality.

This acronym from the 1990s now seems old-fashioned. In the 2020s, the assumption that digital life is not real life no longer rings true. When a child is bullied on Instagram, it’s a real occurrence with real consequences. When you hang out with your family over Zoom, it’s a real family gathering. When you lose money from trading Bitcoin, it’s a real loss. Digital life is an integral part of real life today.

To get to the bottom of this, we need to clarify what it means to be real. Philosophically, there are a few different ways we can define the concept of reality.

First definition: something is real if it makes a difference. The coronavirus is real because it makes people sick. The tooth fairy isn’t real because it doesn’t do anything. Its work is mainly done by parents who tell stories about it and leave money for teeth. In this sense, digital life is real. What happens on the internet affects our everyday lives. A change in Google’s algorithm can ruin a business. A politician’s tweet has the potential to bring down a government.

Second definition: something is real if it’s not just in our minds. A mirage is only in our minds, so it’s not real. A tree falling in the forest happens outside our minds, so it’s real. The internet isn’t all in our minds. Websites still exist while we sleep. Blockchains are present on networks of machines around the world and stay there even when no one is viewing them.

Third definition: something is real if it’s not an illusion, a hallucination or a fiction. In his 1984 novel, Neuromancer, the science fiction writer William Gibson said that cyberspace was a consensual hallucination” experienced by billions of people. These days, I’d argue that cyberspace is a consensual reality. An online store like Amazon is just as real as one of Walmart’s brick-and-mortar stores. Amazon is a full-blooded institution that helps to structure our reality.

Fourth definition: perhaps most important in our digital age, we say something is real if it’s authentic. When something is inauthentic, it’s fake. The physical world is full of inauthenticity, from counterfeit money to fake smiles. Inauthenticity runs even more rampant on the internet, where fake news, phony bots and Instagram filters that idealise our lives abound. Still, there’s plenty of authenticity online. Friendships can be sustained over email. You can genuinely protest against government policy on Twitter. You can enjoy real music on Spotify. Our experiences in digital reality can be just as authentic as our experiences in physical reality. Discussions about what counts as real will become increasingly relevant in the coming metaverse of virtual realities. Today’s virtual worlds, from social worlds like Second Life to game platforms like Roblox, are reflexively contrasted with “the real world”. Many people think virtual realities are unreal by definition. According to my criteria, this is wrong. Virtual worlds are real worlds.

Second Life has made a difference in users’ lives by fostering new relationships and new communities. Roblox continues to exist on servers when no one is looking. The same applies to virtual realities experienced immersively through a headset. For example, the immersive social environment VRChat is more than an illusion: you seem to be having a conversation with other people inhabiting colourful avatars because you really are. Who’s to say these experiences cannot be as authentic and important as the ones that play out in physical reality?

The 2021 movie Free Guy gets this right. Two of the film’s protagonists are nonplayer characters who live in a video game world. Upon discovering this fact, one asks the other: “Does this mean none of this is real?” The other replies: “I’m sitting here with my best friend, trying to help him through a tough time. If that’s not real, I don’t know what is.” This interaction touches on a fifth way to define what is real: something is real if it’s meaningful.

As a philosopher, I think the meaning in our lives is grounded in our consciousness. Human beings are conscious, and this gives us the capacity to invest meaning into the physical world. We can do the same with virtual reality. While an artificial city might not bear the same significance as one’s hometown, virtual worlds will build meaning of their own over time – meaning that comes from us.

None of this means that virtual reality will only be wonderful. Just like physical reality, digital worlds are full of loneliness and pain. And suffering in virtual reality is just as real and as meaningful as suffering in physical reality.

In the future, we’ll be working and playing in digital worlds. We’ll interact with friends and family and build new communities in virtual worlds. It matters whether we can have authentic and meaningful experiences there. I think we can.

Because of this, it no longer makes sense to use “IRL” and “the real world” when talking about physical reality. Instead, we can talk about the physical world and contrast it with digital and virtual worlds. All these worlds can be real.

David Chalmers is professor of philosophy and neural science at New York University and co-director of the Centre for Mind, Brain, and Consciousness. He honorary professor of philosophy at the Australian National University and co-director of the PhilPapers Foundation © The New York Times Company and David Chalmers