The last thing I expected when I visited the wild, offbeat area of Ciociaria, south of Rome – dubbed “shepherd land” – was to find an elegant, Edwardian-style mansion right in the middle of the countryside.

It had ornate columns, wrought-iron balconies and pinkish-green painted walls. It could have been England. The architecture was in sharp contrast to the setting. Ciociaria was known for its brigands, and the people were so poor and had so few prospects that many of them emigrated. All there has ever been here are sheep and cows. Italy’s “far west” was always considered a no man’s land.

But the Ciociaria mansion looked highly sophisticated.

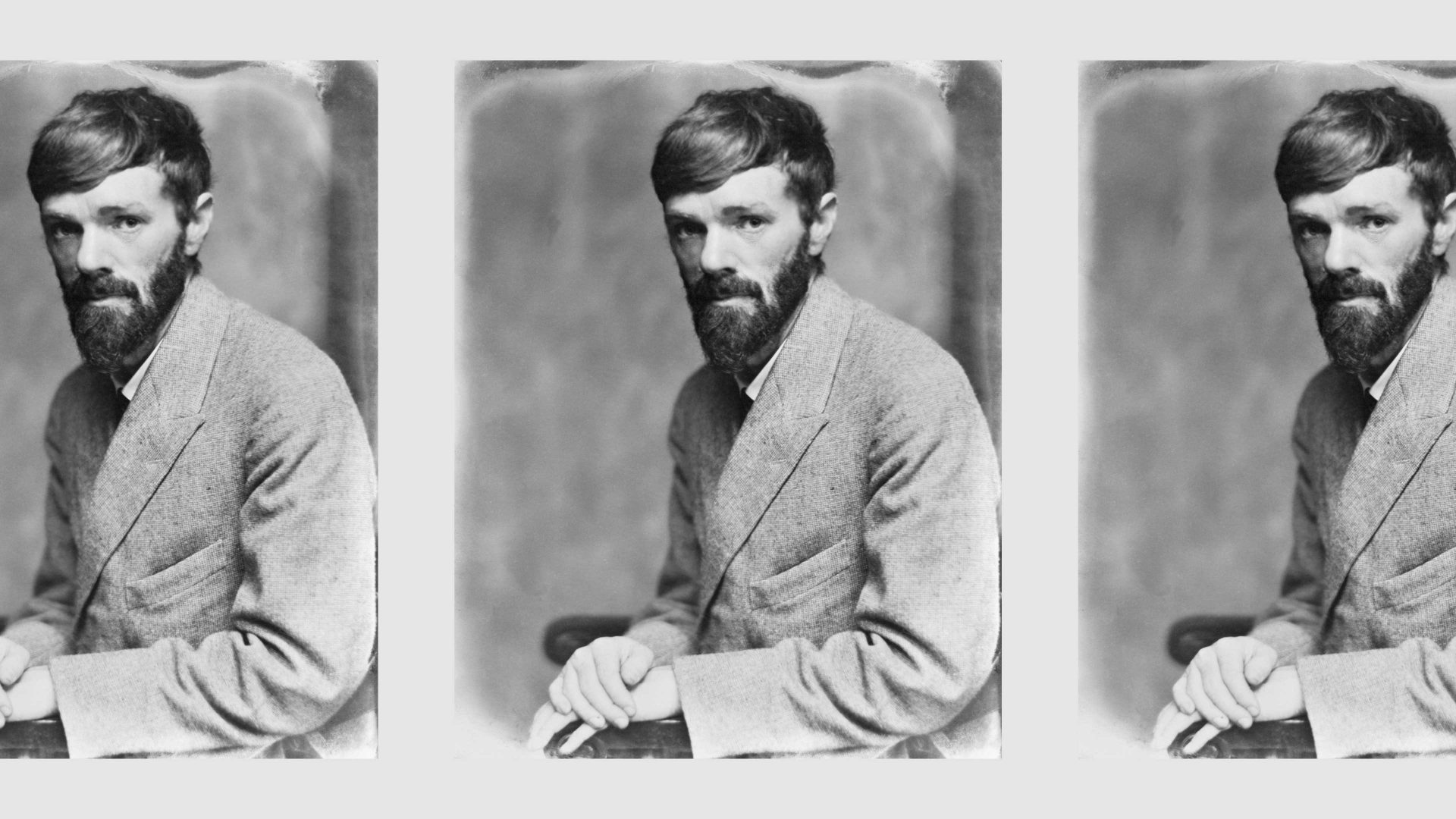

Nowadays it’s owned by a family of shepherds and cheesemakers – they told me it was where DH Lawrence stayed in 1919 and where he had found literary inspiration for his masterpiece The Lost Girl.

Lawrence liked to rub shoulders with farmers and peasants, or at the very least to stay in the same, simple place where they lived. That was in sharp contrast to many of his British literary colleagues who preferred chic Capri and the Amalfi coast.

“Lawrence had been invited to stay here by the owner, an Italian artist who worked in England,” said Lorenzo Pacitti, the current owner. “The author used this mansion as his secret rural retreat that summer, and fell in love with our pristine surroundings.” The villa was rebranded by the Pacittis as “Casa Lawrence” and it has become a hotspot for day trippers and tourists.

A pungent scent of pecorino sheep cheese and freshly sliced black ham mixed with the nasty smell of manure. The surrounding fields were fluorescent green and it hit me how this place was so primitive, which is likely to be what attracted Lawrence in the first place.

The villa has been turned into a B&B with a traditional tavern, where you can have lamb chops with beans and a special kind of spinach called orapi that grows out of the goat dung. I was only told about this nasty detail after I had devoured a plateful of orapi – I have to say, it was delicious. The red wine was good too. It knocked me down in less than three glasses.

Old shepherd shoes – called cioce – hung on the tavern walls alongside dirty sheep hides and rusty farm tools. The rudimentary decor was in stark contrast to the fine, English-style architecture.

There were green-painted outdoor tables for guests to enjoy no-frills rustic brunches including gourmet blue cheese with maggots (I didn’t try it), chestnut honey and fig jam.

The best part was the museum inside, showcasing some of Lawrence’s personal belongings and letters. Visitors can also see Lawrence’s bed, the untidy sheets left there since 1919, with the thick dirty mattress and cover dotted with mould, stains and holes.

At the foot of his bed were two chamber pots (I wondered if they had ever been rinsed), Lawrence’s white nightgown, yellow with age, and his slippers. In the next room was a shiny wooden table in front of a panoramic glass window.

It is said the ghost of a woman haunted that room, and that it was often seen sitting in Lawrence’s chair.

“The author loved this corner of Italy and his time at the mansion, which he writes about in his letters. We’re just so proud of sharing this with visitors,” says Pacitti.

As I read the letters, one of them caught my attention. Lawrence wrote to a friend of his who was planning to come to deep Italy, warning her of thieves and pickpockets.

Lawrence’s vision of Italy wasn’t entirely idyllic. I guessed Pacitti must have missed that part.