Europe’s democracies have been shaken out of their comfort zone. Vladimir Putin’s aggression against Ukraine represents an existential challenge to our continent’s security and values. Sharp rises in energy and food prices, coupled with market turbulence, reminded governments and voters of the fragility of the living standards that millions in Europe have taken for granted.

To those crises add the daunting strategic challenges that Europe faces. China’s open ambition to dominate 21st-century technologies would leave western nations dependent on Chinese know-how and suppliers, and therefore goodwill. The prospect of more frequent extreme weather events is a reminder that the task of cutting carbon emissions is not only urgent, but an international endeavour. To that can be added the threat of terrorism and cyber crime, along with instability in the Balkans and in Africa that offers an opportunity for organised crime to flourish and incentivises thousands to seek a safer and more prosperous life in Europe.

Hardly a surprise that European governments of both left and right have hurriedly rethought longstanding policy assumptions, or that democracies globally have been shocked into remembering that our common interests and the challenges we face are best confronted together, rather than separately.

There are now welcome signs that this collaborative mood is spreading within the UK’s Conservative government. Since coming to office, Rishi Sunak has made clear he wants good relations with the continent. The foreign secretary, James Cleverly, has established a particularly good working relationship with, among others, the German foreign minister, Annalena Baerbock.

Sunak, like his foreign secretary, was a committed Leave supporter in the 2016 EU referendum. He has not recanted that choice, but he still wants good relations. He has highlighted the UK’s commitment to European security, pushing for more military help for Ukraine. He has also improved relations with Emmanuel Macron, and the first formal Franco-British summit since 2018 has been confirmed for March.

Sunak understands that France and the UK are Europe’s two pre-eminent military powers and must work together. He also realises that the road to a deal on both the Northern Ireland Protocol, where France has been the leading EU hawk, and on managing the flow of asylum seekers across the Channel runs through the Elysée Palace.

Sunak’s two immediate predecessors, despite their tendency to use anti-EU rhetoric as a political prop, were perhaps more pragmatic on Europe than they appeared. Boris Johnson, despite huge pressure from the Trump administration, stayed with the mainstream European position on Iran and Israel/Palestine and also made climate a key priority. On Ukraine, he rightly, and in close partnership with Poland, Romania and the Nordic and Baltic countries, took a strong pro-Kyiv stance from the first days of Putin’s invasion.

During her brief stint at No 10 Liz Truss attended the inaugural summit of the European Political Community. She also agreed to UK participation in the military mobility project established under the EU’s Pesco (Permanent Structured Cooperation) arrangements. Her decision was eased by the fact that the US, Canada and Norway had already signed up, but its symbolism should not be overlooked.

But one of the many mistakes made by senior British politicians over the last decade and more was to assume that they could say one thing to their European counterparts and something completely different to the tabloids back home. Most European leaders and their advisers speak and read English and study the British media. I vividly remember on my first ministerial visit to Bucharest being asked at breakfast by a Romanian minister if I could explain to him the significance (or otherwise) of an article that had appeared that morning in the Daily Express.

Every European chancellery had a bulging file of Johnson’s Daily Telegraph articles and referendum campaign speeches. In the eyes of EU leaders, he already carried suspect baggage. His denunciation of the protocol – which he had negotiated, signed and ratified – and his willingness unilaterally to rewrite that deal was the last straw.

Similarly, Truss was welcomed in her early months as foreign secretary, but was later perceived in Brussels, Paris and Berlin (and, for that matter, Stockholm, The Hague and Dublin) as having swerved to a hardline stance on the protocol in order to curry votes among Conservative MPs and party members for a future leadership bid.

Sunak’s approach marks a departure from this tendency to talk from both sides of the mouth. There seems to be a greater sense of realism in his inner circle, and less bombast. The end of January will mark two years since the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) negotiated by Johnson came into effect. That anniversary will pass almost completely unmarked.

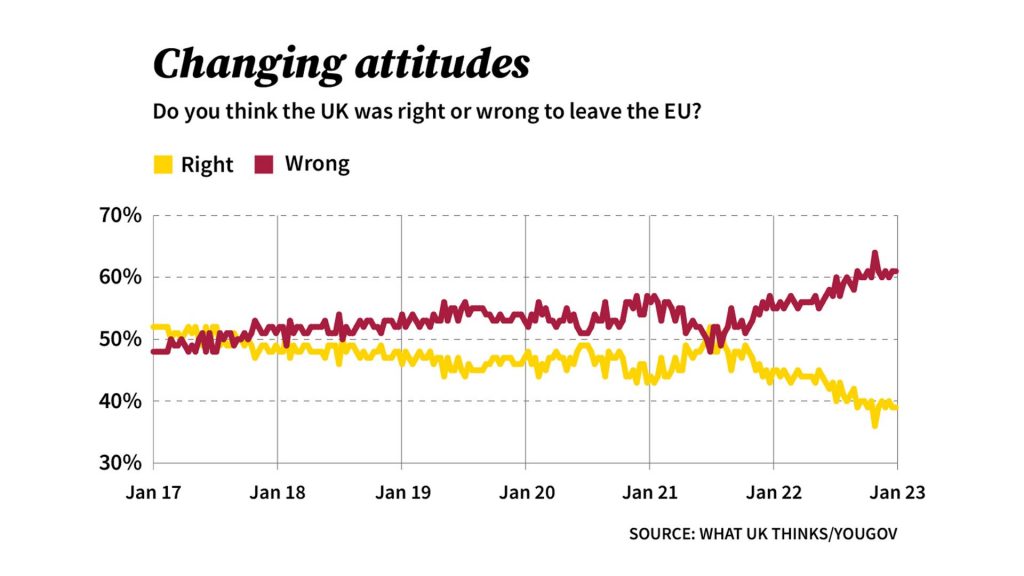

Sunak’s cooler approach to government and his attempt to restore relations with Brussels is in keeping with a perception that Brexit is slipping from the electorate’s list of immediate concerns. Polling for the think tank UK in a Changing Europe found that at the end of 2022 Brexit was not even in the top 10 issues that mattered to the British public. But there has also been a gradual and profound shift in public opinion, a change that No 10 must have noticed. A study of more than 200 polls by the National Centre for Social Research showed that the balance of opinion has now swung strongly against Brexit. Almost 60% now think that leaving the EU was wrong for the UK.

Voters now see that Brexit has not cured all Britain’s ills. Pressures on the health service haven’t eased, and UK companies have not found it easier to trade. Longstanding structural challenges over skills, infrastructure and productivity have not been magically solved.

The shift in public opinion also reflects generational change: every year a new cohort of predominantly pro-European 18-year-olds is added to the electoral register and older voters die. People in the Conservative Party know this and realise that, if they want to win future general elections, the party will need to appeal more to younger, more internationalist-minded voters who at present break overwhelmingly for Labour. Pragmatism on Europe is not an electoral panacea – housing and climate are more important. But appearing reasonable when it comes to relations with Europe is a necessary part of a successful electoral pitch.

But there is a limit to how close Sunak, and whoever might follow him into No 10, can get to Europe. Having closer, more constructive relations with other European countries and with the EU is one thing, but actually rejoining is quite another. Few people would be enthusiastic about another referendum, with all the bitter divisions and infighting that would bring. It would also be a huge distraction from the many other pressing problems Britain faces. What’s more, rejoining would not be Britain’s decision alone – the appetite among the EU 27 to embark on re-accession negotiations with the UK is limited in the extreme. It won’t happen unless and until there is a consensus across both centre-left and centre-right in UK politics that Britain should rejoin.

Whether that consensus ever emerges will depend on the UK government’s ability to reach agreements on a host of different issues. During 2025 and 2026 the trade agreement, the fisheries agreement, the EU’s decision on UK data adequacy and the current policy on derivatives trading will all come up for review with the EU. There is also the matter of the protocol, as well as a vote, scheduled for December 2024, in which the Northern Ireland Assembly will decide whether to stay in the trading arrangements set out in the protocol.

Some elements in all this look possible: London accepting the legal status of the protocol and its requirement for a framework of checks and controls between Great Britain and Northern Ireland; Brussels agreeing to a very significant reduction in the practical impact of those controls; an enhanced role for elected representatives of Northern Ireland in the implementation of the deal.

Others look to be harder going. There is a risk that the European Commission underestimates the political importance for Sunak of amending the role Johnson agreed for the European court of justice.

But if a deal can be done, other moves will then become possible. The Memorandum of Understanding on Financial Services, agreed in principle two years ago, could be finalised. The UK’s participation in the Horizon research programme could move forward.

But before the next UK election, which is likely to take place in the autumn of 2024, No 10 will only be able to make incremental changes and Sunak will still need to keep an eye on his hardline backbenchers. He has an electoral tightrope to tread. He needs to avoid losing Johnson-supporting Leave voters to the Farageist Reform party, while also holding on to Tory Remain voters who might be drawn to Keir Starmer’s newly reformed Labour. Both Sunak and Starmer have ruled out a European Economic Area-style relationship with the EU.

But incremental improvements are still worth having. If trust can be established on the smaller issues, this could pave the way for cooperation on bigger strategic questions – for instance on climate and energy security.

In the medium term, increased practical security cooperation ought to lead to a more formal, structured security partnership between the UK and EU. The closer coordination between Nato and the EU that has developed because of the Ukraine crisis ought to lessen the UK’s nervousness about the EU encroaching on Nato’s responsibilities.

Effective cooperation on European security is a process that involves EU institutions as well as national governments. Last year’s events have also reminded EU leaders that effective security and defence requires the active participation of the UK. That in turn will need something more than an occasional invitation from the Foreign Affairs Council for the UK to sign up to something they have all agreed.

That kind of deal is probably something for the next British government, whether led by Sunak or Starmer, and it could form the basis for a fresh start in UK-EU relations. There are good reasons to be hopeful about the year ahead.

David Lidington is a former UK Europe minister and deputy prime minister. He is chair of the Conservative European Forum and the Royal United Services Institute