It was, in most respects, just another Friday night in Rome. Cars packed the

streets sounding their horns as scooters wove between them. Tourists gawped, locals promenaded and the great and the good were out to see and

be seen.

It was August 15 1958, and photographer Tazio Secchiaroli was looking for celebrities, preferably doing something they shouldn’t. When he found the deposed King Farouk of Egypt sitting in a café on the Via Veneto with two women, neither of whom were his wife, it was exactly the kind of thing Secchiaroli’s editors paid him for.

The former monarch leapt up angrily and ran at Secchiaroli. The photographer hopped on to his Vespa and took off, following a tip that Ava

Gardner was outside another café looking very intimate with married co-star Tony Franciosa – who became the second person that night to make a grab for the photographer.

With those shots in the can, Secchiaroli moved on to where Anita Ekberg and her husband Anthony Steel were emerging from a car having clearly enjoyed a few drinks. Steel completed a hat-trick of physical altercations for the photographer in the space of an hour.

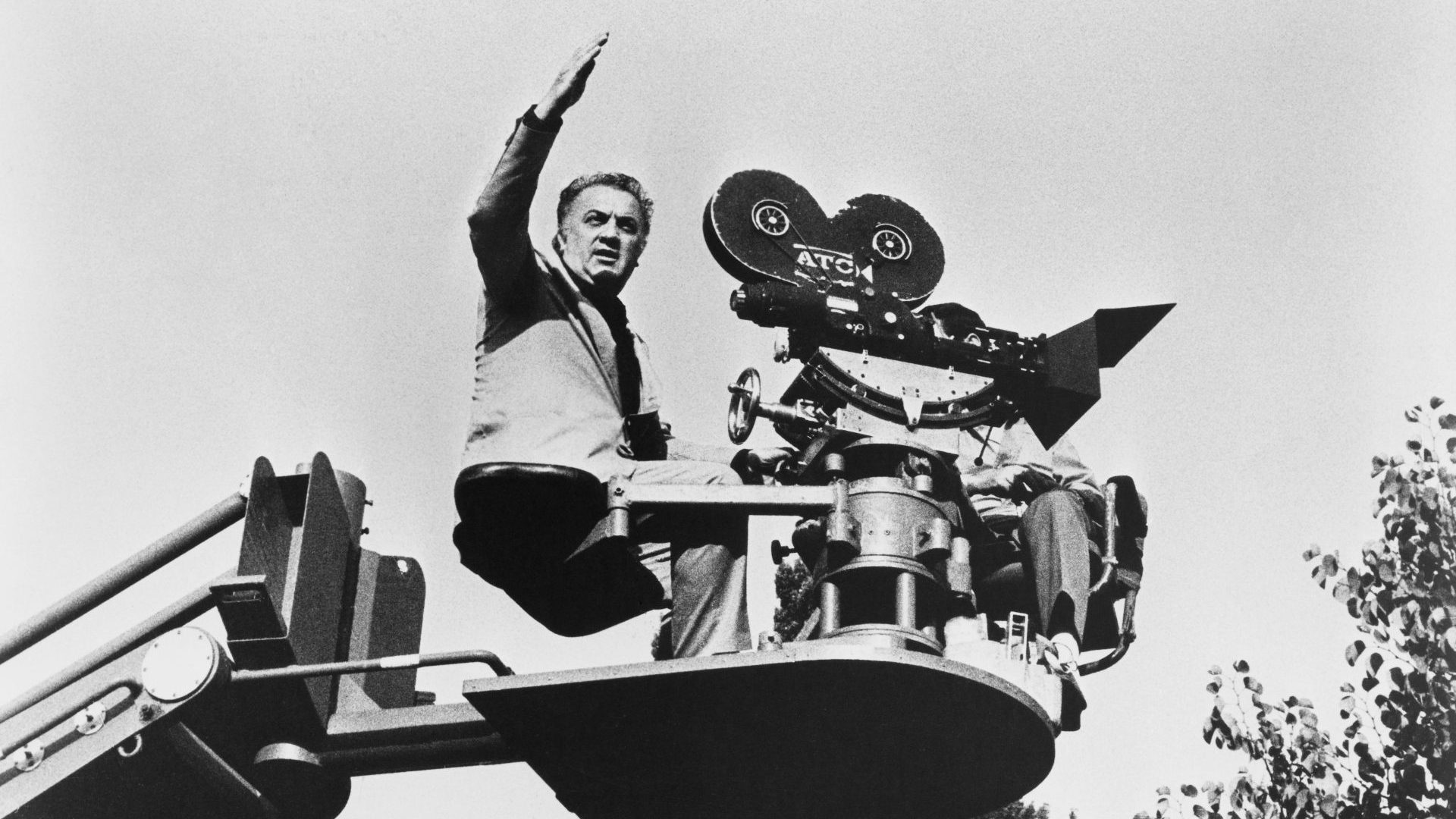

Shadowing Secchiaroli that night was Federico Fellini. He’d been planning a

film about the triumph of contemporary bohemian Rome but instead found a city running on the fripperies of celebrity rather than its substance. Gossip, not talent, was the currency of the day, and Secchiaroli and his ilk were its bankers.

This, Fellini realised, was Rome now, the Rome he sought to document. Nights like that humid August Friday watching a photographer being chased

through the streets by a succession of aggrieved notables gave the director the core of his film.

That film was La Dolce Vita, a beguiling portrait of glamorous sleaze in a city emerging from the trauma of the war years into its latest reinvention as the playground of celebrities.

Fellini’s camera follows Marcello Mastroianni’s gossip columnist Marcello Rubini through a week of sourcing scandal and tittle-tattle, all the while wrestling with the knowledge that he was walking on a flimsy veneer of guileless hedonism over a yawning chasm of ennui.

So accurate was the film’s depiction that Rubini’s photographer Paparazzo, a thinly veiled version of Secchiaroli, lent his name to an entire profession.

Released in 1960, La Dolce Vita somehow managed to capture the spirit of the coming decade in addition to being a perfect distillation of Fellini’s two main cinematic characteristics: exuberance and sentiment. It was also, like all his

films, personal. Rubini represented Fellini’s own internal battle with a growing weltschmerz. The director even cast Ekberg, whose famous scene with Mastroianni in the Trevi fountain was based on a real-life incident involving Ekberg herself.

The last scene, in which Mastroianni watches some fishermen drag a giant fish from the waves, is also drawn from Fellini’s life.

“It’s a childhood memory of a sea monster that a storm had thrown up

on the beach at Rimini,” he said in 1971. “I always wanted to make use of

it. In La Dolce Vita it seemed to fit as an expression of absurdity, irrationality.”

The fish presents an enigmatic conclusion to the film, one that has been debated throughout the 60 years since it was released, but for Fellini himself, meaning was less important than immersion in the combination of sounds and images coming from the screen.

“Meaning, always meaning,” he complained when quizzed. “When someone asks, what do you mean in this picture, it shows he is a prisoner of intellectual, sentimental shackles. Without his ‘meaning’, he feels vulnerable.”

Searching for meaning was too close to letting in daylight on magic for one of cinema’s greatest-ever filmmakers. Fellini’s projects were all personal – he

once joked: “even if I set out to make a film about a fillet of sole it would still be about me” – because for him there was practically nothing separating life

from film and vice versa. Demanding “meaning” only risked a stumble while

walking that blurred line between the real world and the screen. Cinema for

Fellini was life itself, with all its interweaving stories, impressions and chaos.

“When I am not making movies,” he said, “I feel I am not alive.”

It was in the cinemas of his home town of Rimini that Fellini developed one of the most keenly attuned cinematic minds there’s ever been. One of his earliest memories is of standing at the back of the Folgor Cinema with

his father watching Maciste all’Inferno (Maciste in the Underworld), released in

the twilight of the silent era when Fellini was six years old. The film charted the eponymous hero’s descent to hell to fight demons and romance goddesses, but everything about that night made an indelible impression.

“I’m sure that I remember it well because the image has remained so deeply impressed that I have tried to re-evoke it in all my films,” he said. “I saw it standing with my father’s arms around me in a crowd of people in wet overcoats because it was raining outside. I remember a large woman with nude belly, her belly button, her eyes darkened with make-up, blazing.”

It was as if the dreams he had at night were up on the screen, a projection if

not beamed directly from his subconscious, then certainly drawn from the same place.

“When I was about six or seven I was convinced that we lived two existences,

one with our eyes open and one with them closed,” he recalled. “I couldn’t

wait to go to bed in the evening. I had named the four posts of my bed after

the four cinemas in Rimini – Fulgor, Savoia, Opera Nazionale Balilla, and

Sultano – and the show began the moment I closed my eyes. First a velvety darkness, deep and transparent, a darkness that led into another kind of darkness. Then the darkness was punctuated by flashes: a bit like the sea at night, when a storm is brewing and the horizon is bombarded by lightning.”

For all Fellini is held up as the ultimate chronicler of Rome in the 20th century, it’s Rimini that made him and Rimini that inhabits his films, a place

he described as “confused, frightening, tender, with that great breath of its own and its empty, open sea”. The town featured directly in projects such as 8½, Amarcord and I vitelloni as well as being conjured in scenes like the monster fish finale of La Dolce Vita.

Rimini was his projector, the Adriatic the screen for his imagination. While a

combination of childhood excursions to the cinema and his own nocturnal

inventions spawned in Fellini a unique vision that changed the language of

cinema, at its heart lay a bold simplicity.

“I’m just a storyteller and the cinema happens to be my medium,” he said. “It’s not just an art form; it’s actually a new form of life with its own rhythms,

cadences, perspectives and transparencies. It’s my way of telling a story.”