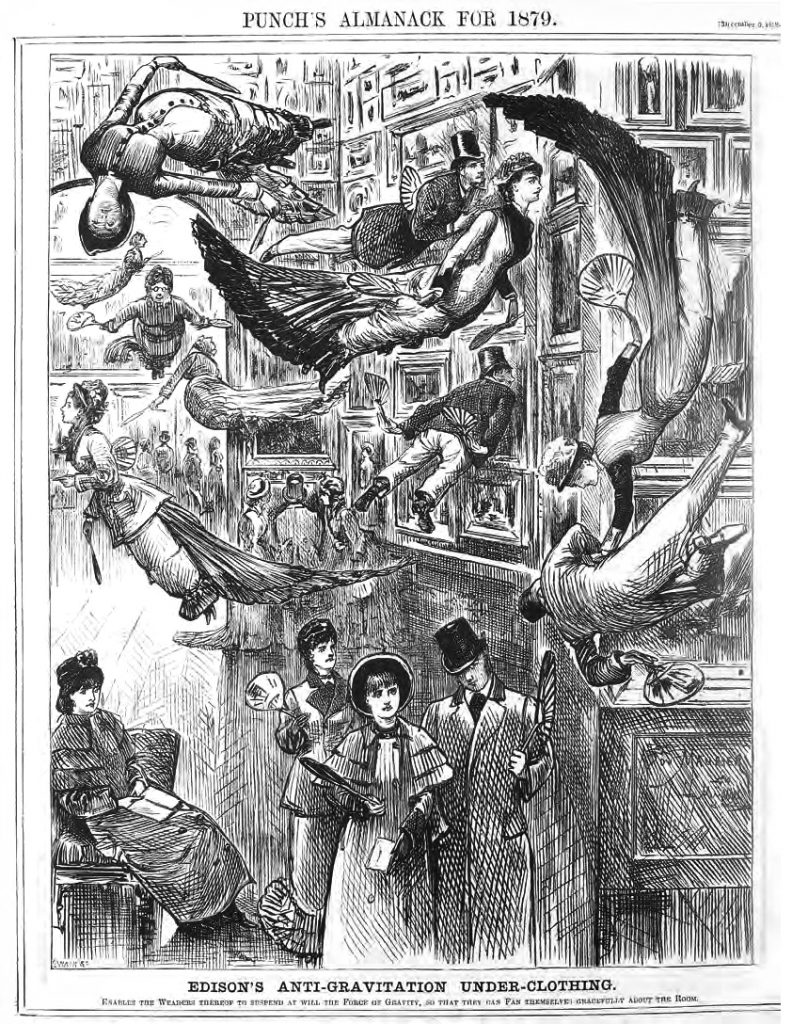

Edison’s anti-gravity underwear never really caught on. There is an 1878 cartoon of the aerial garments being used by smartly dressed Victorians who are soaring up towards the ceiling at an art gallery to examine paintings otherwise too high to view.

Disappointingly, the flying undies existed merely in a whimsical Du Maurier cartoon in Punch. It is reproduced as one of the intriguing illustrations in Extinct: A Compendium of Obsolete Objects, by Barbara Penner and a team of observers, who, between them, examine and analyse 85 devices for which their time has passed or never came at all. Some, however, seemed to die, only to re-emerge. They were simply ahead of their time, or at least their time’s technology.

In 1958, German genius and architect Werner Ruhnau came up with the oxymoronic concept of “air roofs”. Along with French artist Yves Klein, he took further the familiar idea of a warm-air curtain that blows down at the entrance to shops.

Ruhnau enthused about “compressed-air canopies” which would keep out the weather and thus replace the slates and bricks of physical buildings. Sadly, this has – so far – turned out to be so much hot air.

Another invention that disappeared into thin air was the “atmospheric railway”, which did away with a heavy, steam-puffing engine completely. One version of this was road-tested, or rail-tested, near Dublin. Carriages would be powered by suction from pipes laid alongside the tracks. A different method proposed for the London Underground envisaged giant fans to swoosh the train along.

Sadly, the first scheme was defeated by rats eating the leather sealing mechanism and the second by a crash — of the bank funding it. Elon Musk’s current plans for “hyperloop” transportation, along vacuum tunnels, is uncannily close to the original thinking.

There was a significant German development that did fly, in both senses: the Zeppelins. These airships were used for bombing raids in World War I then for luxury travel over the Atlantic and Europe —until May 1937, when the 800ft Hindenburg, filled with hydrogen, exploded and burned to a cinder in less than a minute, deflating the whole idea of the majestic dirigibles, for a while at least. Today, the Zeppelin company is back in business, and producing hydrogen airships with fit-for-purpose safety systems.

The wartime Zeppelins had been able to play a lethal game of hide-and-seek under the cover of darkness or behind clouds. The British military solution was an “acoustic location device”. Gramophone ear trumpets fed the sound of the airship’s engines, via a stethoscope, into each ear of the operator. He would pass the compass bearing on to anti-aircraft gunners.

Blind men, whose ears were supposed to be keener, were eagerly recruited. This primitive sonar system was replaced in the 1930s by an early type of radar.

Given the scarcity in the late 1930s of the long, costly runways necessary for heavy aircraft, the flying boat had years of service, being able to land on rivers and lakes. By contrast, the flying car took off but landed with a bump shortly afterwards.

The ConvAirCar, as it was known, was a lightweight saloon with a small aircraft fixed to its roof by large pins which would be removed after a flight. An early demonstration was not helped by the hybrid craft running out of fuel over its airfield. Investors pulled out and it never went into production. Drone technology now makes such “flying taxis” an investable prospect once more.

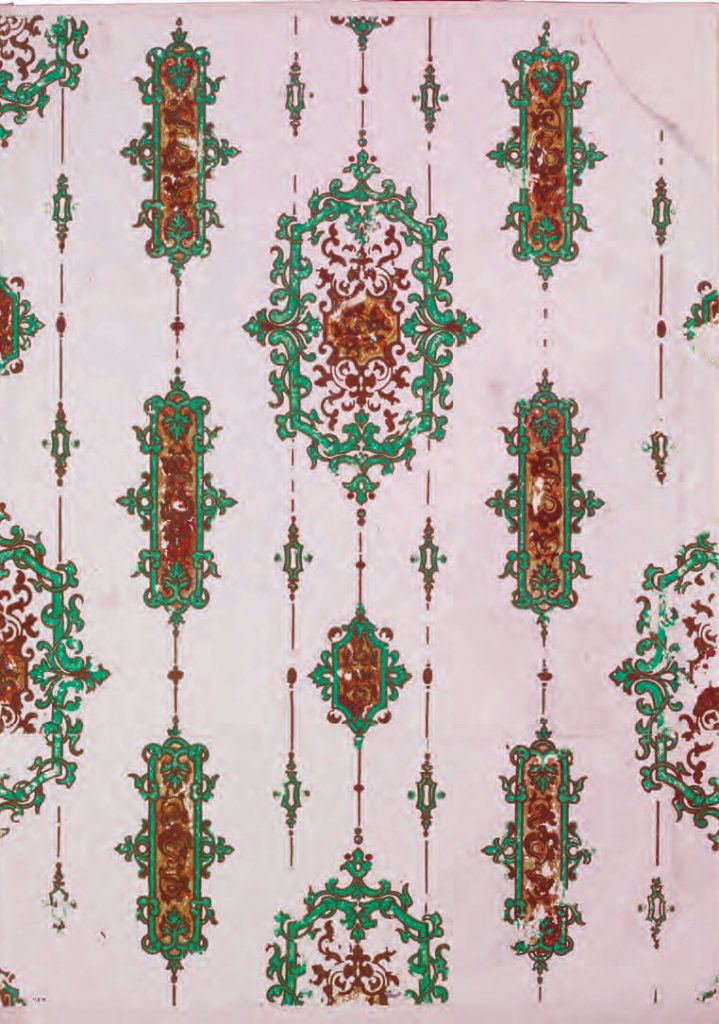

Wallpaper coloured by a vivid green pigment invented by the Swedish-German chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele in 1778. It became known by a variety of names, including Scheele’s Green, emerald green and Paris green.

Another name gives a hint of why it was subsequently withdrawn, after being found to cause lung and skin problems, painful inflammation and in some cases, death by poisoning. Scheele’s invention was also known as arsenic green. Such a shade was imprinted upon the wallpaper in Napoleon’s St Helena bathroom and quite possibly did for the ex-emperor.

Other artefacts may look like technological dinosaurs but still enjoyed a lengthy lifespan. At a time when early gramophones could only produce rather scratchy, distorted music, the “player piano” was like a human piano player. As with its cousin, the pianola, it was essentially live music, with strings being struck by the customary hammers operated by scores on paper or metal rolls before your very eyes and ears.

Once modern record players and hi-fi arrived, the player pianos could bow out. But the átrophone also had a good run for its audiences’ money, beginning in 1881 in Paris and lasting for more than half a century.

Microphones on stage in a Paris opera house or theatre would transmit voices via the newfangled telephone system to individual homes; Le theatre chez soi, as it was marketed. Members of the “audience” for this acoustic streaming would call a switchboard and be put through to the theatre of their choice.

Although not all of these gizmos are expected to be reincarnated any time soon, Extinct asserts that even the most bizarre of inventions still have something to show us:

“Every extinct object embodies a vision of the future that is still available.”

The re-emergence of airships, flying cars and vacuum travel – once all ideas thought dead as dodos – are examples of a great idea not dying, merely hibernating. Flying underwear, on the other hand, is still awaiting a revival.

Extinct: A Compendium of Obsolete Objects edited by Barbara Penner, and others, is published by Reaktion Books.