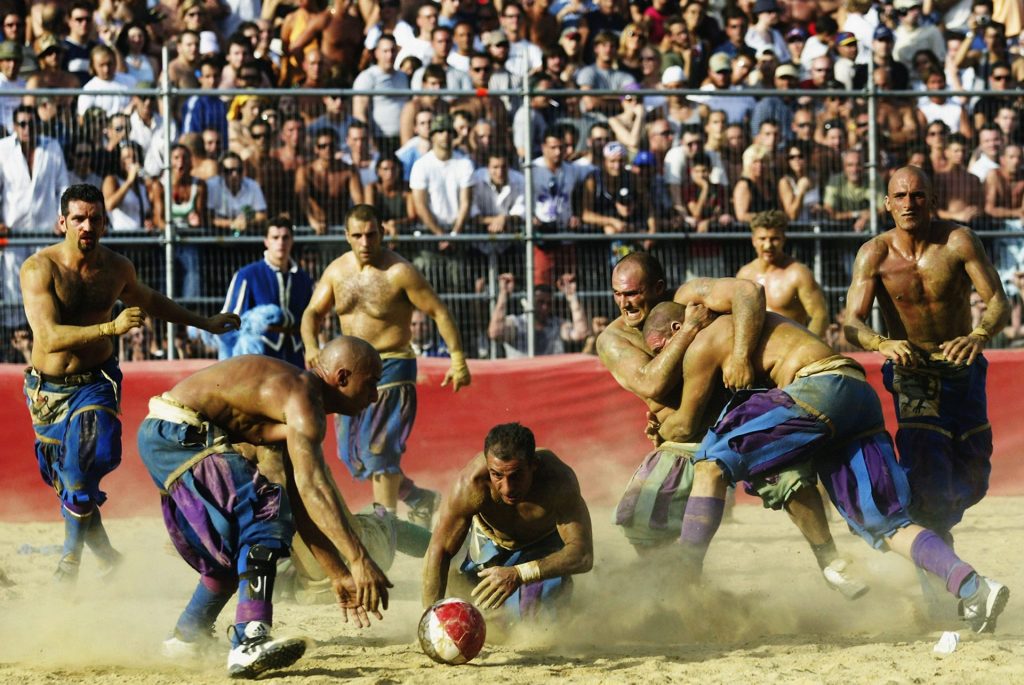

Firenze: the birthplace of the Renaissance, in the heart of lush Tuscany. History and culture are etched in its ancient walls, can be found around every corner. However, on June 24, the city stopped and thousands gathered to watch 54 bare-chested men wearing brightly coloured medieval pantaloons punch and kick each other in a giant sandpit for 50 gruelling minutes.

Calcio Storico – literally historical football – is a 500-year-old annual tradition unique to Florence. Just four colori (teams) take part, each representing one of the city’s quartieri, or neighbourhoods: the Azzurri di Santa Croce (Blues), the Rossi di Santa Maria Novella (Reds); the Bianchi di Santo Spirito (Whites) and the Verdi di San Giovanni (Greens).

There are just three games: two semi-finals, which take place in early June, and a final, which traditionally takes place on the feast day of John the Baptist, the city’s patron saint, and in which this year Azzurri beat Rossi. All games are played in Piazza Santa Croce in the shadow of the 15th-century Basilica that shares its name, the resting place of luminaries such as Michelangelo, Machiavelli, Galileo and Rossini.

The calcinate (players) are all unpaid volunteers aged between 18 and 40

(although most are in their 30s). Sons follow in the footsteps of their fathers

and grandfathers. They come from various backgrounds: some work in construction sites or bakeries, others, like marketing executive Andrea Piras,

have white-collar jobs. On the pitch, they are equals.

“If you’re not part of it, you might say ‘these guys are just crazy’,” chuckles Piras, who helped the Rossi to victory in 2019. “Then there’s our point of view. It’s a big honour and responsibility because you are representing your neighbourhood and setting an example for younger generations.” For the calcinate, the game is also about being part of something bigger. “There are extremely tight bonds between us, we share the pain and the joy for many

months,” says Piras. “When we get to the field, we think as one.”

There are no medals or prize money for the winning team, just a Chianina

calf, which is divided up and cooked into the regional speciality, Bistecca

alla Fiorentina, and city-wide recognition. However, for the losers the 12 months after defeat are tough. “It’s not like soccer where you can say ‘OK, next weekend I’ll do better’,” says Piras. “If you lose, you have to wait another year to put it right.”

Raised in the Santa Maria Novella district, Piras became aware of Calcio Storico when he was at primary school, watching his first game aged 11. “I have always been passionate about the history and tradition of Florence,” he

says. “I felt Calcio was part of my city and part of me. From there it was a natural step to take part. At first, I was a little bit suspicious because, of course, it is not an easy sport, but it was love at first sight.”

What might to the untrained eye might look like a no-holds-barred pub brawl involving members of two historical re-enactment societies is in fact a game with rules and tactics. “When you watch it for the first time, it looks like a big, big mess,” says Piras. “When you start to play, everything makes sense. The guys in the field are trained for a specific reason to do certain movements; to attack or defend in a certain way.”

The aim is to score by getting the ball into the opposition caccia, a low netted trough that spans the 40m width of the pitch. However, if the ball goes over the trough, the opposition is awarded half a point.

Players can run with the ball or kick it. Teams traditionally line up with four goalkeepers, three defenders, five midfielders and 15 forwards. The midfielders run with the ball, the defenders and goalkeepers defend the net. Piras is a forward, “where the fun happens”, he says. Their job is to fight the opposition to both incapacitate them and create openings for their teammates. Rugby-style tackling, grappling, punching, kicking, headbutting and even choking are all permitted. However, players are not allowed to sucker punch an opponent from behind, nor double up on an opposing player.

It also requires discipline from its players both on and off the pitch. “You

don’t need to just be strong, you have to have the right mentality,” says Piras.

“You can’t think as an individual; you have to think as a teammate.” Players

train on their own in other sports, such as rugby, MMA and boxing, before coming together to prepare for the games. “Each one of us has to be ready physically and technically,” he says. “Then we train with the ball. We do movements and tactics; we are learning strategies. So when we’re playing we don’t have to think.”

Surrounded by temporary stands in the Piazza Santa Croce, the rectangular playing field is about the size of a standard football pitch, divided into two equal squares. The surface is a 16-inch layer of dirt and sand covering the cobbles below. This is done partly as a throwback to the early games and partly as a concession to prevent injury. It is the only one.

The searing mid-summer sun means dehydration and exhaustion are common. “You have to be in good shape,” says Piras. “There are no substitutions, so you can’t say after 10 minutes ‘OK, guys, someone else needs to take my place’.” Medical staff are on hand to conduct running repairs on the players, but it is expected that about seven or eight from each team won’t finish the game. In the final this year, two Rossi players were stretchered off.

Piras has broken both a shoulder and a knee in training, but has finished the games themselves relatively unscathed. “I would say ‘luckily’, I just broke my hands,” he tells me. “That means I punched too hard.” Although no one has died, serious injuries do happen. In 2013, 10 players needed hospital treatment, and in 2019, Fabrizio Valleri, a forward for the Bianchi, spent more than a week in intensive care after a kick left him with several broken ribs and a punctured lung.

Given the obvious risks, it’s understandable that players go through a range of emotions in the minutes before entering the field. “Some are tortured by tension,” says Piras, “some are worried, some start to really concentrate. Personally, I feel happiness because I feel the city, I feel the tradition I’m taking part in. I am one of these people who becomes calmer in stressful

situations. When the game is happening, everything slows down. I see what I was prepared for.”

As its name suggests, Calcio Storico provides an insight into what the pre-codified antecedents of modern football were like. It’s believed that the

game was derived from the Roman sport of harpastum, which was used to

train soldiers and was itself based on a similar ancient Greek ball game. However, as with the more famous Palio di Siena and Pamplona’s bull run, Calcio Storico is as much about pageantry, civic identity and pride as it is about what happens on the field.

The game that underpins the modern iconography of Calcio – the procession before the final, the medieval-style costumes – took place in 1530, during the siege of the city by the Spanish-backed army of Emperor Charles V, which ultimately restored the Medici as rulers of Florence.

Unwilling to allow the siege to mute the city’s civic tradition, the Florentines organised a Calcio tournament with all the usual carnivalesque pomp and ceremony on February 17 in the Piazza di Santa Croce, in earshot of their enemy outside the city walls. The teams were drawn from the Florentine army’s four battalions, each representing one of the city’s four administrative districts.

The decision to play the game in defiance of the enemy at its gates embedded Calcio Storico in Florentine folklore: the make-up of the teams on

the pitch representing the administrative divisions of the city, the event itself emblematic of its unity and courage in the face of adversity.

Monteforte/AFP

Half a century later Giovanni de’ Bardi, a friend of the Medici family, published the first set of rules, also arguing that “one might believe that the game was introduced to the city at the same time as it was founded”. Calcio Storico had become linked with the foundation rite of the city enacted through the pageantry of the annual San Giovanni Battista (St John the Baptist) feast day celebrations.

Over the course of the next 300 years, Calcio Storico continued to be played but its significance waned, and games became less frequent. The so-called ultimo Calcio, the last officially organised game, took place in 1739. After that, it became a historical footnote until in 1930, on the 400th anniversary of the game played during the Siege of Florence, it was revived by Benito Mussolini as part of the fascists’ re-imagining of a range of secular festivals and church processions.

However, Piras says the game is not just a representation of something done in the past; it has renewed meaning for contemporary Florence. “It is something live, something going on now and this is why people are so passionate about it. It started in the past, but it is something we really, really feel belongs to us now.”

At the same time, he acknowledges that not all Florentines are fans of the

game. “There are different opinions. Some are sceptical because they think we are a little bit violent. But even the people who don’t watch it recognise

you are putting your body and soul on the line to keep this tradition alive.”

This has not always been the case. The popularity of the game suffered in the late 1970s when a player had their ear bitten off, and the tournament was suspended for a year after a mass brawl led to 50 players being taken to court in 2006. At that time, tensions often spilled out of the arena and into the city’s streets.

“Twenty years ago, this was happening daily, and the reputation of Calcio Storico was really low,” Piras tells me. “I have no issues if you punch me on the field; that’s part of the game, but I don’t want any trouble outside.” To combat this, new rules were imposed, the most significant being one banning players with serious criminal convictions.

The tournament was cancelled again in 2020 as Florence, like the rest of Italy, was hit hard by Covid. “The city really struggled. Many people died,”

says Piras. “The games being cancelled was an additional defeat. I always say

it was like missing Christmas, or your birthday.” A proposal to move them to

September came to nothing, the lack of training time meaning players could not prepare properly.

In 2021, with the pandemic ongoing, there was renewed determination for the games to take place. Filippo Giovannelli, the event’s director, argued that it was important to keep the tradition alive “to feed the fire that burns in the hearts of Florentines”. They were again going to be moved to September although without spectators or the usual procession; the games would just be broadcast on TV.

The four colori were given the choice of whether to take part, Bianchi and Rossi declining to do so. “Our team manager asked us if we were willing to

play and we all said no, because it is something done for the city, not the TV,”

says Piras. Thus, there was just one match: a win for Azzurri against Verdi.

Piras did not take part this year, either. Unable to train as much as needed, he withdrew, unwilling to let his teammates down. Instead, he watched from the stands as they were beaten 11.5 to 7.5 by Azzurri in a game widely regarded as one of the best of recent years. “Unfortunately we lost, but it was a great match; amazing, I’d say,” he says.

Despite the defeat, he could see beyond what took place in the arena and what the game meant for Florence. “I felt like a teenager watching Calcio Storico for the first time. The city and the square were vibrant again.”

Roger Domeneghetti is a journalist, author and a lecturer in journalism at

Northumbria University