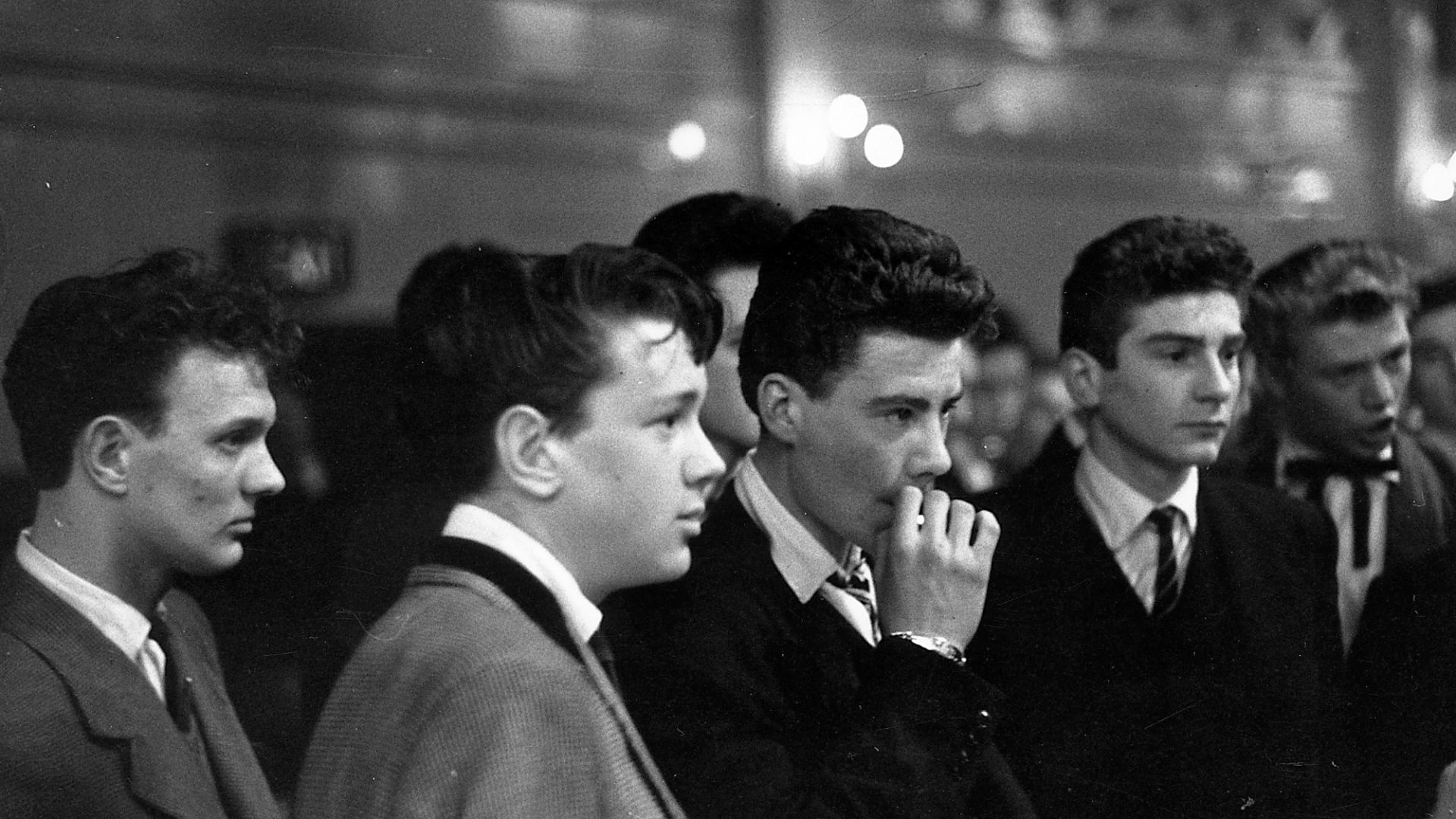

As a youth movement, the British working-class Teddy Boys of the early 1950s arrived fully formed and startlingly original.

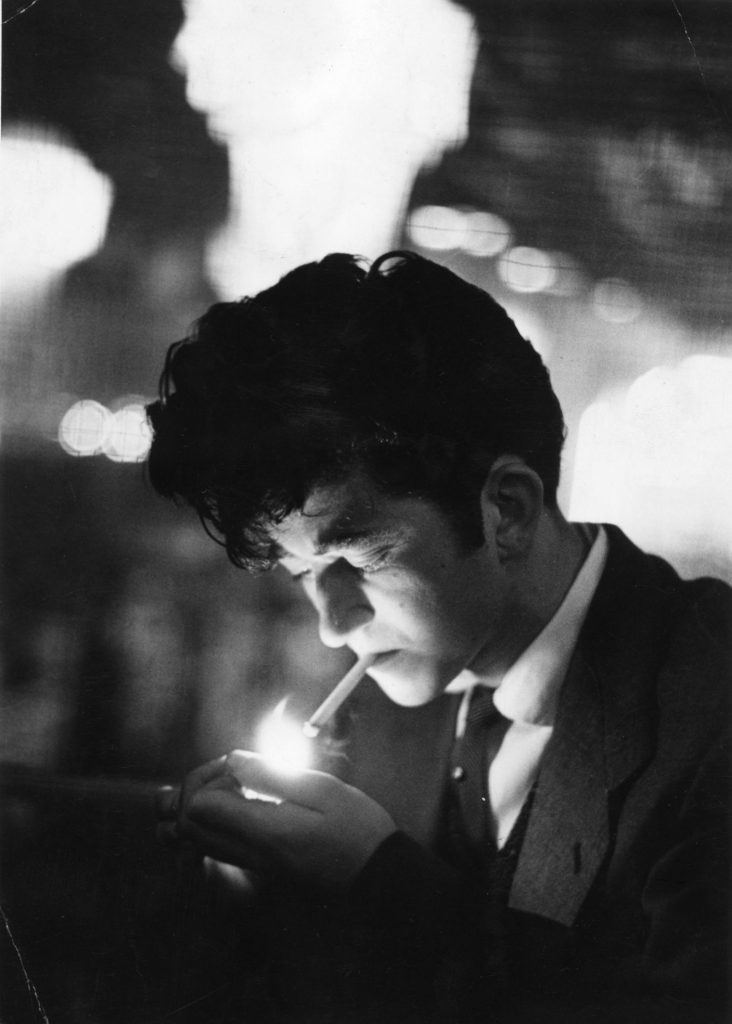

The origin of the name “Teddy Boy” though disputed, seems to derive from the habit of wearing Edwardian-style clothes, and the classic look – subverting Savile Row’s own simultaneous attempts to market those styles to the wealthy – combined velvet-collared long draped jackets with narrow drainpipe trousers, gaudy waistcoats, thin ties and crepe-soled shoes known as brothel creepers. Hair was greased up and carefully styled into what was known as a DA, or duck’s arse.

The recent war had killed enough of the working population that 1950s employers struggled to fill vacancies and had to pay decently for even unskilled manual labour, thereby producing a new generation of teenage school-leavers with enough money in their pockets for clothes, records, dancing and cinemas, who built a whole subculture of their own – prompting significant resentment among the adult population.

Initially a London movement, they made national headlines in the summer of 1953, and by the end of that year the style had been adopted by considerable numbers of young people across the UK, Teddy Girls as well as Teddy Boys. They were sharp, they were different, they embraced American rock’n’roll when it first appeared over here in 1954, and paved the way for every British youth movement that followed.

Yet while their behaviour also occasionally generated shock-horror reports filed by the London correspondents of foreign newspapers, Teds remained essentially a British phenomenon.

Early Teds acquired a reputation in the tabloids as hooligans, and the name quickly became a lazy shorthand term applied to any young person falling foul of the law, often regardless of how they were dressed. Indeed, the extent to which the name “Teddy Boy” had become an insult in some quarters can be judged by an interview given by the brother of deceased IRA man Fergal O’Hanlon, shot dead in a 1957 attack on the RUC barracks in Monaghan, who told the press “we are not Teddy Boys – Fergal was no Teddy Boy”.

Employing the loosest possible definition of the term, British newspapers of the day seemed to be holding a competition to see who could report the most ludicrous sighting of supposed Teddy Boys in all corners of the globe. The Guardian claimed to have located the “Teddy Boy type” in Nigeria in 1954, and the Times found them in Malta a year later, but genuine London Teds would have struggled to recognise the following description of an alleged Russian example of the breed that appeared in the same paper in 1957 under the headline “Soviet Teddy Boy”.

“A typical leading article in Izvestia gave a graphic picture of the Soviet hooligan and Teddy Boy. ‘Trousers stuffed stylishly into his boots, a sports cap pulled well forward, a false tooth, the latest hair cut, and shifty eyes.”’

Boots? Sports cap? Clearly, the terms of reference involved were now so loose as to become meaningless.

Undeterred by questions of accuracy, in 1959, the same paper claimed that there were “feuds between Teddy Boy gangs and secret societies” in Malaya, and that in Athens, the authorities were sentencing trouble-makers to parade through the streets wearing placards reading “I am an ass and a Teddy Boy”.

In 1959, the Guardian reported a “Teddy Boy plague” across Italy, and that “Teddy Boys and rock’n’roll are now to be found even in Salzburg and Passau, and are not to be avoided in Munich and Nuremburg”, while the Times – which appears to have had something of an obsession with the subject – helpfully informed readers that there were Teddy Boys in Venezuela, called pavitos.

Throughout the 1960s, news items in the British press identified supposed overseas Ted movements in places such as Sweden, Hong Kong, South Africa or India. Then, proving that the confusion worked both ways, the peak of absurdity was reached in 1978 during the punk/Ted disturbances in London when an Icelandic newspaper confidently reported that bass player Jean-Jacques Burnel of the Stranglers had been beaten up by “Teddy Bears”.

Unsurprisingly, when you scratch beneath the surface of such reports, it becomes clear that these teenage gangs in other countries had precious little to do with anything happening in England. Although most working-class British teenagers of the 1950s could not take holidays abroad, some authentic Teds found their way overseas doing compulsory National Service in the armed forces or working in the merchant navy.

Many young Teds were conscripted, and a fair number served in Germany, but as the Spectator reported in 1956, much of what had made them distinctive had been removed: “Shorn of his hair, his eccentric clothes and his familiar urban terrain, the Teddy Boy is an isolated figure.” Around the same time, future writer Daniel Farson worked on a merchant ship alongside a couple of Teds, and they went ashore in San Francisco, as he later recalled:

“Teddy the Teddy Boy walked beside me in his velvet collar, his hair carefully styled into a DA. ‘They look at us as if we’re from Mars,’ he said, irritated by the astonished glances.”

In 1961, when the House of Commons debated a bill entitled Corporal Punishment for the Young, Gerald Nabarro MP spoke of “the nuisance we in Britain call Teddy Boys and Girls. In Germany they are called Halbstarke (half-matured); in France, Blousons-noirs (black-jackets).”

Like the tabloid press, he was confusing the leather-jacketed European teenagers in quasi-American clothing inspired by Marlon Brando in The Wild One or James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause with the very different Edwardian styles of genuine Teds, but to the older generation, they were all simply juvenile delinquents.

The Ted movement made little headway across the Channel during those decades, yet lurking beneath the surface a persistent fascination about such people had been developing in many European countries. In Italy, early rock singer Adriano Celentano enjoyed a hit in 1959 with a song called Teddy Girl – “Oh Teddy Girl, pupa in Technicolor / Oh Teddy Girl, c’è un juke box nel tuo cuor” (“Oh Teddy Girl, Technicolour doll / Oh Teddy Girl, there’s a jukebox in your heart”).

The following year, Domenico Paolella made the musical film Mina e i Teddy Boys della Canzone (Mina and the Teddy Boys of Song), while author and future film director Pier Paolo Pasolini wrote a screenplay of a more serious kind about the young men in Milan who identified as Teds, eventually published in 2013 as La Nebbiosa (English title, City of Mist).

British crime writer Nicolas Freeling, who lived much of his life in France and the Netherlands, included Dutch Teddy Boys in his debut Van der Valk novel, Love in Amsterdam (1962) and its follow-up, Because of the Cats (1963), while the Greek film industry gave the world a 1965 comedy feature film called Teddy Boy, Agapi Mou, directed by Giannis Dalianidis, then the 1967 comedy, O Manolakis, O Teddy Boys, directed by Vangelis Melissinos. Neither bore much relation to British Teds, but nor did Diana, Princess of Wales, whose new hairstyle in 1986 was optimistically claimed by the Daily Express to be a throwback to the classic Teddy Boy DA of the 50s.

However, despite all these multiple false trails involving a wide variety of countries, an authentic Teddy Boy influence began spreading across mainland Europe during the 1970s whose effects are still being felt today, rooted in the UK rock’n’roll revival of that decade, some of whose bands wore drapes and sang about Teds.

A prime example was South Wales rockabilly outfit Crazy Cavan & the Rhythm Rockers, whose 1973 debut single was called Teddy Boy Boogie, followed in 1974 by another entitled Teddy Boy Rock’n’Roll. They had a powerful impact internationally, and their incendiary live performances inspired many European musicians over the following decades.

By the 1980s, there were young bands such as The Teen Cats, from Norway, who performed in velvet-collared drape jackets, appeared regularly on national television and covered Cavan’s Teddy Boy Rock’n’Roll as the title track of their LP in 1989. In the 1990s, a drape-jacketed German band from Düsseldorf named themselves Black Raven in honour of one of London’s main Ted pubs of the 1970s, and there was an Austrian rockabilly band from Vienna called the King Edward Teds, who spawned an offshoot, the Edwardian Devils.

The First Scandinavian Teddy Boy Festival took place in Finland in 1998, attracting bands and enthusiasts from many different countries, and these days in Vantaa, Finland, there is a regular rocking night called the Dixi Teds Rock’n’Roll Club, while in the Mediterranean, a band from Mallorca called the Wild Coffees describe themselves as Teds and cover Cavan’s Teddy Boy Rock’n’Roll, one of many such bands on the international rocking scene.

This shared interest in a particular style of dress and music now regularly blurs national boundaries, and has proved powerful enough to bring people from different countries to bespoke events such as the 2018 Rock’n’Roll Weekender held in the tiny Brittany village of Saint-Gorgon (population 414) to watch the likes of Black Raven, UK outfit Phil Haley & His Comments, and draped-up French group the Blood Teds, or to more long-running gatherings like the annual Rock’n’Roarin’ Festival in Madrid.

Of course, the UK Teds of the early 1950s were unusual in that they were a youth movement not initially linked to any particular style of music, having existed for two or three years before rock’n’roll hit Britain. There were no Teddy Boy bands playing in drapes in those days, yet various Teds wound up becoming famous musicians, John Lennon and Paul McCartney being the obvious examples.

In addition, 21st-century European society is in many ways very different to the Britain of 1953 that the London Teds and Teddy Girls were rebelling against, just as the social and economic conditions that produced the mods of 1964 or the punks of 1976 were specific to their respective eras. Times have changed greatly, but the essential youth culture fashions have survived.

Largely shorn of its more nuanced associations, the classic Teddy Boy look took many years to catch on as a style choice across the Channel, yet today you’re just as likely to encounter drapes and creepers at specialist music festivals in mainland Europe as in the UK – although your chances of finding anyone there with “a sports cap pulled well forward, a false tooth, the latest hair cut, and shifty eyes” are probably minimal.

Teddy Boys: Post-War Britain and the First Youth Revolution by Max Décharné is published by Profile Books