It was almost midday when we spotted the distant forms of two hikers on the ridgeline ahead of us. “Must be the girls from Menorca,” my wife guessed.

We’d last seen the two young women bandaging their blisters in a little hostel several evenings before but I was sure that Narina was right. After all who else could it be on these remote trails?

“Jerry is probably a day ahead by now,” I mused. “And Niki is almost certainly several hours behind us.”

After a week hiking along Galicia’s least-known Camino route, we were familiar with all the other hikers in this section of the Sil Valley. Jerry, an Irish ironman-pilgrim who was making his eighth long-distance hike, had a reputation for a particularly rapid pace. The lone Zimbabwean hiker Niki, meanwhile, would still be tramping her way through the thick pine forests where earlier that morning we’d come across the fresh tracks of a small pack of wolves.

It was hard to imagine that, barely 20 kilometres to our north, the main route of the world-famous Camino de Santiago would be crowded with an endless procession of thousands of anonymous hikers. Many would be rising in the predawn darkness, such was the rush to get to the next albergue before the bunks (allocated on a first-come-first-served basis) were all taken.

While upwards of 440,000 pilgrims arrive in Santiago de Compostela each year via the Camino Francés (the French Way), only an estimated 1,000 or so walk the so-called Winter Way that runs along the southern flanks of the mountains.

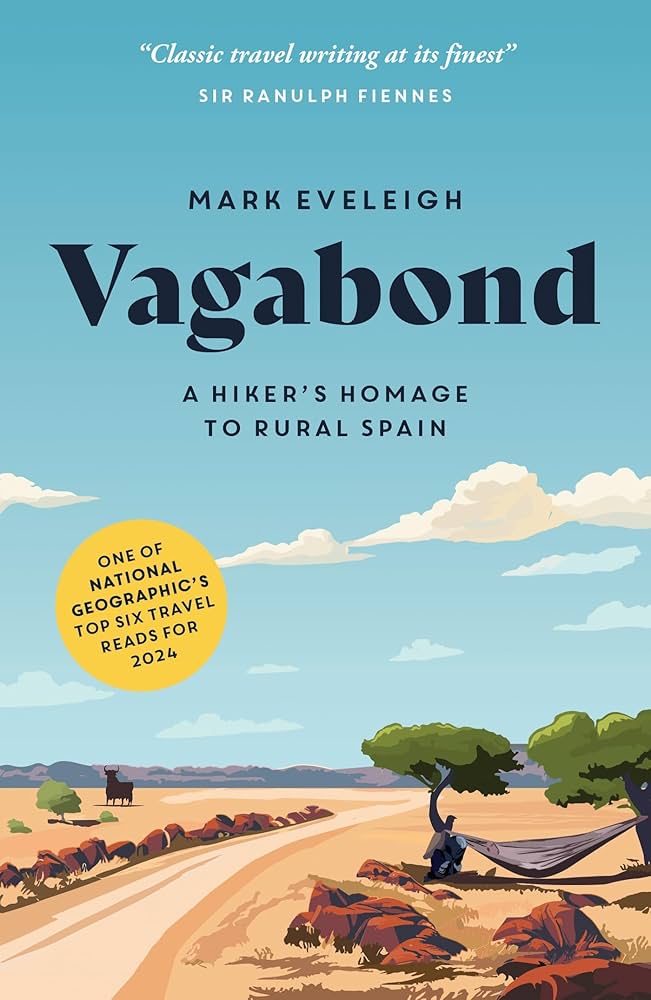

I’d been intrigued by the many barely known alternatives to the world-famous Camino since I hiked coast-to-coast across Spain, researching my new book, Vagabond. That 1,225km solo hike, at the ripe old age of 54, was made more challenging still by the fact that I’d slept rough – either in my trusty hammock or simply on the rocky Spanish ground on the treeless plains of the high Meseta.

In the first month on the trail I’d only encountered 20 other hikers. It had come as something of a shock, therefore, when my route coincided with the French Way and I fell into step for a few days with what appeared to be a ragtag refugee column of hundreds of footsore wayfarers.

The Galician highlands can be extremely bleak, even in midsummer, so it’s hardly surprising that medieval pilgrims established what they called the Camino del Invierno (Winter Way). Lying in the southerly rainshadow of the mountains, it avoided the worst of the blizzards. In 2016 this route was incorporated into the growing list of official trails that lead to the hallowed city of Santiago de Compostela.

More recently, small numbers of experienced hikers had come to the realisation that the Winter Way was an appealing alternative at any time of the year, so it was not entirely unusual that Narina and I had set out on our “winter walk” on midsummer’s day.

With a starting point in the city of Ponferrada, the Winter Way is 267 kilometres long, but we’d planned to set off instead from farther east in Astorga. While it would bring our total distance to 319 kilometres, I knew that the first two days spent on the crowded French Way would provide a powerful contrast to the subsequent solitude of the southern hills.

Sure enough, we hiked out of Astorga amid a parade of pilgrims that stretched as far as the eye could see across the rolling hillsides. The shuffling progress of some left it in no doubt that they felt every centimetre of the 510 kilometres they’d already marched from Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port (just beyond the French border). Our hearts went out to a few who – like the tail-enders in a zombie movie – looked unlikely to complete the remaining 257 kilometres before finding “salvation” in the form of Santiago de Compostela’s 900-year-old cathedral.

Narina and I slept the first night in a converted convent in the highland village of Foncebadón and the next morning we embarked on what is rated to be the hardest stage of the French Way as we climbed to the high pass. The spot is marked by the Cruz de Ferro (Iron Cross) which was raised by an 11th-century hermit who was celebrated for protecting pilgrims from bandits and the feral dogs that were said to roam these hills until relatively recently.

These days, fortunately, Cruz de Ferro is more famous for one of the most evocative traditions of the Camino: it is at this point where pilgrims traditionally lighten their load (both metaphorically and literally) by depositing a stone that they have carried from their distant home. As Narina and I ceremonially deposited lava rocks that we’d collected for this reason near our little Balinese beach house, it occurred to me that – after a thousand years of such deposits – the ever-growing heap at the foot of the Cruz de Ferro would make rich pickings for a geologist.

Our still tender feet were feeling every one of the day’s 25 kilometres when Ponferrada’s ancient Knights Templar castle loomed on the horizon late that afternoon. Out of every 400 or so pilgrims on the French Way only one is likely to opt to turn south to follow the Winter Way along the steep flank of the Sil Valley.

The Winter Way is hillier and longer than the more direct route but we were in no rush and figured that 13 days would be ample to cover the entire route from Ponferrada to Santiago. It is surprising that this alternative is not more popular since it should appeal to the many would-be pilgrims who are unable to sacrifice the five weeks or more that are usually recommended to complete the main Camino route.

While these northern mountains tend to escape the worst of Spain’s brutal summer temperatures the long midsummer daylight hours allow for ample walking time. When the trail was particularly dusty we covered our mouths and noses with our buffs (known in colloquial Spanish as bragas cuello – neck knickers).

There was time for picnics of serrano ham and country bread in the plazas of sleepy siesta-hour villages where the only sound was the staccato clatter of storks’ bills, like tiles falling from the chapel roof. We enthusiastically embraced the tradition of the siesta too, stringing our double hammock between mighty chestnut trees (some of which may have been planted by the Romans).

We’d often walk for several hours between villages and we carried supplies since cafes and bars were few and far between. In the village of Santalla del Bierzo we asked a woman if there was somewhere to buy provisions. She immediately paused in trimming her garden hedge to prepare coffee and toast for us on her sunlit patio: “Estáis en vuestra casa,” she said (“You’re in your house”).

I’ve often found that there’s a tradition of hospitality in rural inland Spain that has long since disappeared from the Mediterranean coast. “Buen camino,” farmers and vineyard workers call out as you pass, and “Vaya con Dios” (Go with God). It’s the timeless greeting of old Spain.

Several times we came across remote homesteads and hamlets where the inhabitants had set up what are known as donativos – offering snacks and drinks (even once a Nespresso machine) that are ostensibly free for pilgrims… but which, in effect, you repaid with a donation.

Departing before dawn one day, a well-meaning cafe owner had insisted on providing an extra wake-up call in the form of a shooter of fiery homemade liquor as an accompaniment to my morning coffee. I might have been tempted to refuse had it not been for the fact that the two Guardia Civil officers along the bar seemed also to consider it the ideal start their day.

“Salud!” they called, raising their stumpy glasses. “Cheers” and “Vaya con Dios.”

By the time we’d passed the ancient mines at Las Médulas – once the most valuable goldmine in the Roman Empire – I felt that we were plumbing the depths of what my daughter calls “Deep Spain”. Raised with her mother in the northern city of Pamplona, she finds it hard to appreciate the thrill that I get from visiting remote communities which these days have all too often been abandoned by a generation that yearns for the city lights.

We passed our evenings in backcountry bars and our nights in simple pensiones and albergues (with dorms for pilgrims) but as the days passed we began to regret that we were nearing the end of our hike and only wished we had time to go “deeper” still into backcountry Spain.

On the last day we veered off the ancient paving stones of a 2,000-year-old Roman road to chat to a farmer who was driving a small herd of the pale cattle that are known in this area – with no hint of irony, it seems – as Rubias Gallegas (“Galician Blondes”).

As we continued on our way, a scrappy terrier came bulleting out of the farmyard, barking enthusiastically. Without a moment’s thought I span around and bellowed at him. The guttural curse I dredged up from somewhere – the sort of typically horrible “Deep Spanish” blasphemy that should not be committed to type – came as a shock even to myself.

Fortunately, Narina didn’t understand. The terrier, however, clearly got the message: he skidded

to a halt with his bark turning to a shrill whine and retreated back the way he’d come.

Mark Eveleigh is the author of Vagabond: A Hiker’s Homage to Rural Spain, published by Summersdale, £10.99