Just a few months ago, there was a clear story about vaccination across Europe: the UK had got it right and almost everywhere else had got it wrong. The UK at one point had the highest vaccination rate of any major country in the world and seemed to have an unassailable head start against its neighbours.

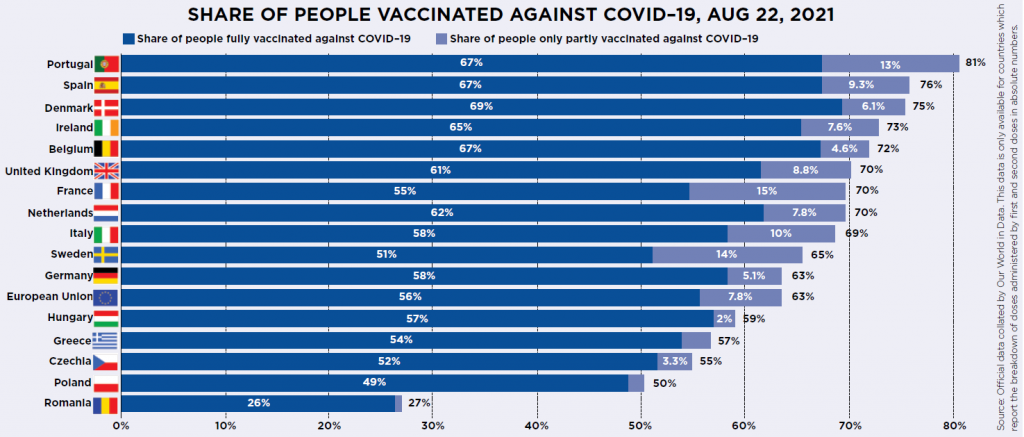

Now we’re at the end of August and things look very different. Not only does the UK not have a head start anymore, it’s been overtaken. The UK has fully vaccinated 61 out of every 100 people. Already Portugal (67 per 100), Spain (67), Belgium (67) and Denmark (69) have surpassed us in terms of the percentage of their population who are fully vaccinated, as well as those who have had one dose.

The EU’s performance across the world is also looking much better too: the EU average – now 56 people per 100 fully vaccinated – recently overtook the USA (51 per 100). America had been vaccinating at a lightning speed but has lost all momentum due to huge levels of vaccine resistance and indifference, particularly among Republicans.

But does any of the above really matter? We are vaccinating our populations to halt the progress of a pandemic that has killed millions and done untold economic damage.

Given that for as long as any of us are at risk, all of us are at risk, what really matters is getting the world’s population vaccinated as soon as possible, rather than winning some nationalistic race, especially when the virus is able to mutate more rapidly when it is able to spread quickly and readily through largely-unvaccinated populations.

So we might be able to put our egos aside and accept the UK is dropping down the international charts – but does our lower relative position versus some of our neighbours mean we’re less protected? Not necessarily.

Who has had the vaccine is much more important than how many vaccines have been dispensed. While the Delta variant is more dangerous for younger people, age remains the biggest risk factor, by some margin. Covid is still far deadlier for over-80s than over-70s, and deadlier for them than over-60s and so on and so forth, to the point that for younger adults the chance of death (though not long-term illness) is virtually zero.

The UK’s staged rollout, starting with the oldest and most vulnerable groups, couple with relatively low vaccine resistance, means that a huge proportion of our most vulnerable residents are double vaccinated. Compared to the US in particular, we have seen much lower levels of hospitalisation and deaths versus our level of infection.

Also confounding the headline statistics – this time versus Europe – is that several EU countries have opened up jabs to everyone aged 12-17, while at present the UK is only vaccinating vulnerable people (or their relatives) in this group. While this may prove to be the right decision, it does mean the headline figures for those countries are boosted by people in one of the lowest risk groups.

The Delta variant has, though, changed the nature of the vaccination game. The good news is that a double dose of vaccine does seem to be incredibly effective against hospitalisation and even more effective against death – reducing the latter by 95% or more.

The bad news is it seems certain that the Delta variant can infect the double-vaccinated, which also means they can spread the illness, even if they’re less likely to do so than the unvaccinated. That scotches hope of herd immunity, the only means of protecting people who can’t (because of allergies, immunosuppression or existing conditions) or won’t get vaccinated.

It therefore raises the bar for what authorities need to do with the vaccine – we still protect each other by getting it, but not so much as before. That means we need to vaccinate almost everyone, not just the 70% or 80% that would have been needed for the original pathogen.

That’s also before we consider the risk that coronavirus mutates further – which, when we have vaccination rates of 20% or below in most of the world’s countries remains a very high risk.

The vaccine’s effectiveness is facing very real world testing: both the UK and the US are seeing relatively high numbers of coronavirus cases once again – both around 45 cases per 100,000 people, a little over half the January peak. This is particularly alarming in the US where many older adults are not vaccinated and where cases have climbed sharply: in July the USA had just four cases per 100,000 people, so the recent spike is sudden.

The EU, by contrast, has far lower case rates than either the US or UK – the current average there is just 12 cases per 100,000, and has been steady for a month, relieving some pressure off the pace of vaccination.

But only to an extent: we are most at risk of coronavirus developing further resistance to vaccination while we have partially vaccinated populations – and a mutation in one country can quickly become a global problem, as Delta showed us.

We don’t need to treat vaccination as a race, but we do all need to hurry towards the finish line.