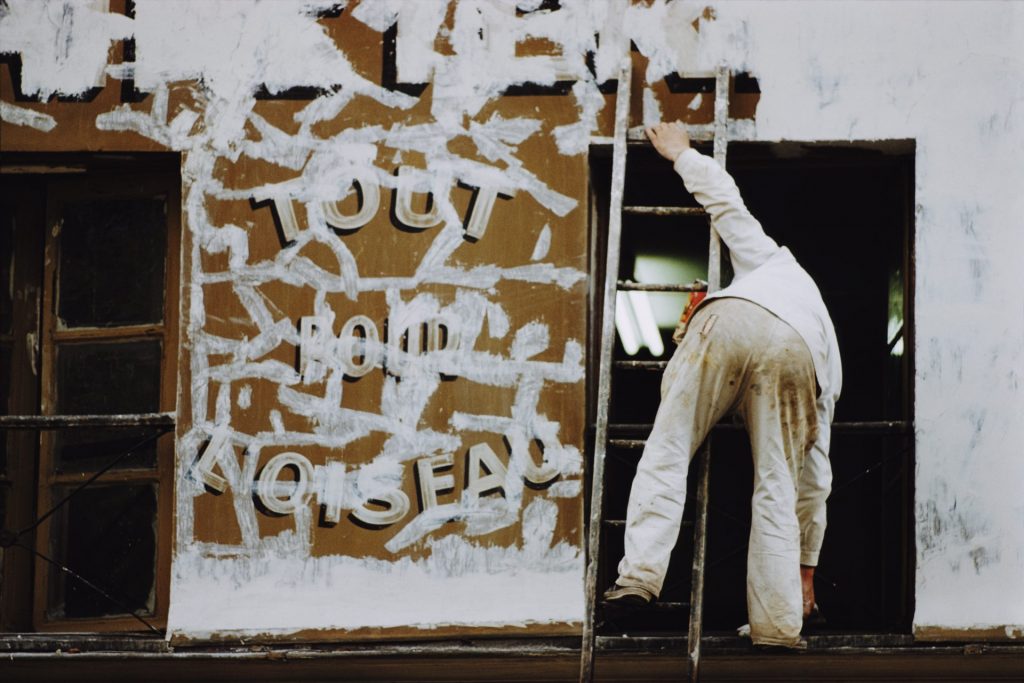

‘Haas seemed to work with the city to create a new visual definition of Paris’. Clockwise: Visitors near Nôtre-Dame, 1955; prospective purchasers check the goods at a book market; men fishing on the Seine, 1954

Many of us have seen Paris, the city of light. But few have seen the light of the city like Ernst Haas.

Haas, who called himself “a painter in a hurry”, was born in Vienna in 1921. He was 19 and studying medicine when he inherited his father’s camera and darkroom. Eight years later, and now a photojournalist of note – thanks in part to images of his war-ravaged hometown that appeared in LIFE magazine – he moved to the French capital, joining the picture agency Magnum at the request of its co-founder, Robert Capa, the master of combat photography. His new colleagues included the great humanist Henri Cartier-Bresson and the Italian-American Paris chief of staff Maria Eisner, a talented photographer and expert organiser.

Haas’s photos from that period are memorable: a gendarme struggling for control of traffic near the Arc de Triomphe, a shirtsleeved Capa looking for inspiration in the Magnum office, the langour of a cafe in the afternoon, the shadows cast by men in hats as a woman smokes at an outdoor table in Montmartre. But they are as nothing next to the images that would follow when he returned to the city in the mid-1950s, now on assignment from his new home in New York.

Haas, who would later reflect that “all my inspirational influences came much more from all the arts than from photo magazines”, was beginning to operate in the space between photojournalism and art photography. A shoot in the New Mexico desert had left him longing to bring colour into his work. Could colour film, then in its infancy and tarnished by its association with commercial photography, really capture the moods, the authenticity, the light and shade, the stark and the sepulchral that mono did in the hands of Haas’s Magnum colleagues?

The answer given by Haas’s first colour essay, on New York for LIFE in 1953, was an unequivocal yes. Spread across 24 pages in two instalments, it was titled “Magic Images of a City”. Hailed by the critic Andy Grundberg as bringing “photography into the precincts of abstract expressionism”, it was a rebirth for photography, and for Haas. “Looking back, I think my change into colour came quite psychologically,” he said later. “I will always remember the war years, including at least five bitter postwar years, as the black and white ones, or even better, the grey years. The grey times were over. As at the beginning of a new spring, I wanted to celebrate in colour the new times, filled with new hope.”

Yet he was determined to push the new medium as he embraced it. “Having the possibility to express a world in colour through colour, I was searching for a composition in which colour became much more than just a coloured black & white picture,” he wrote. Haas gave up the Rolleiflex camera, a photojournalist staple, for a smaller, 35mm Leica rangefinder and chose Kodachrome film for its rich, saturated colours. His printing methods doubled down on saturation.

In the images on these pages, taken in 1954 and 1955, Haas and the city seem to be working together to create a new visual definition of Paris; one that is very different to his vision of New York as a grid of action. Haas’s Paris is a dreamlike city of reflections, blurs and silhouettes that reveals itself at sunrise, in the twilight, in frames shaped by bridges and monuments. Many photographers and film directors have returned to this thought – think of Jules and Cynthia’s misty morning walk in Jean-Jacques Beineix’s Diva – but playing with overexposure, soft focus and shallow depth of field, Haas was the first to begin to describe Paris in what he would later call a “new hieroglyphic language of light and time”.

He went on to be voted president of Magnum, to become an acclaimed stills photographer for Hollywood and to sell 350,000 copies of his 1971 book Creation, one of the best-selling photography collections of all time. And until his death in 1986, Haas continued to innovate, creating abstract, painterly works – many involving blurred motion – that also showed insight of and empathy for the cities and people he captured on film.

As the American photographer and curator Edward Steichen said: “He is a free spirit, untrammelled by tradition and theory, who has gone out and found beauty unparalleled in photography.”