Cannes in the rain. The crowds of festivaliers – the biggest attendance figures in the event’s 76-year history – smoke and bitch miserably in the

queues which stretch around the Palais and down into the jaws of the underground car park. We arrive at the theatres, the famous Debussy and the Grand Théâtre Lumière, hot and wet, and not in a good way.

You don’t care. You laugh at my first-world problems, Cannes in the rain. But it’s all anyone can talk about. Until the movies begin.

Movies change Cannes. They decide the mood, part the grey clouds. A great

film sends shivers buzzing along the Croisette, from the Palais to the Martinez. Hell, the three-and-a-half-hour Martin Scorsese premiere made me forget about Arsenal throwing the title away at Nottingham Forest. I’m

glad I went to a movie instead of watching that – I needed to sit down in a darkened room.

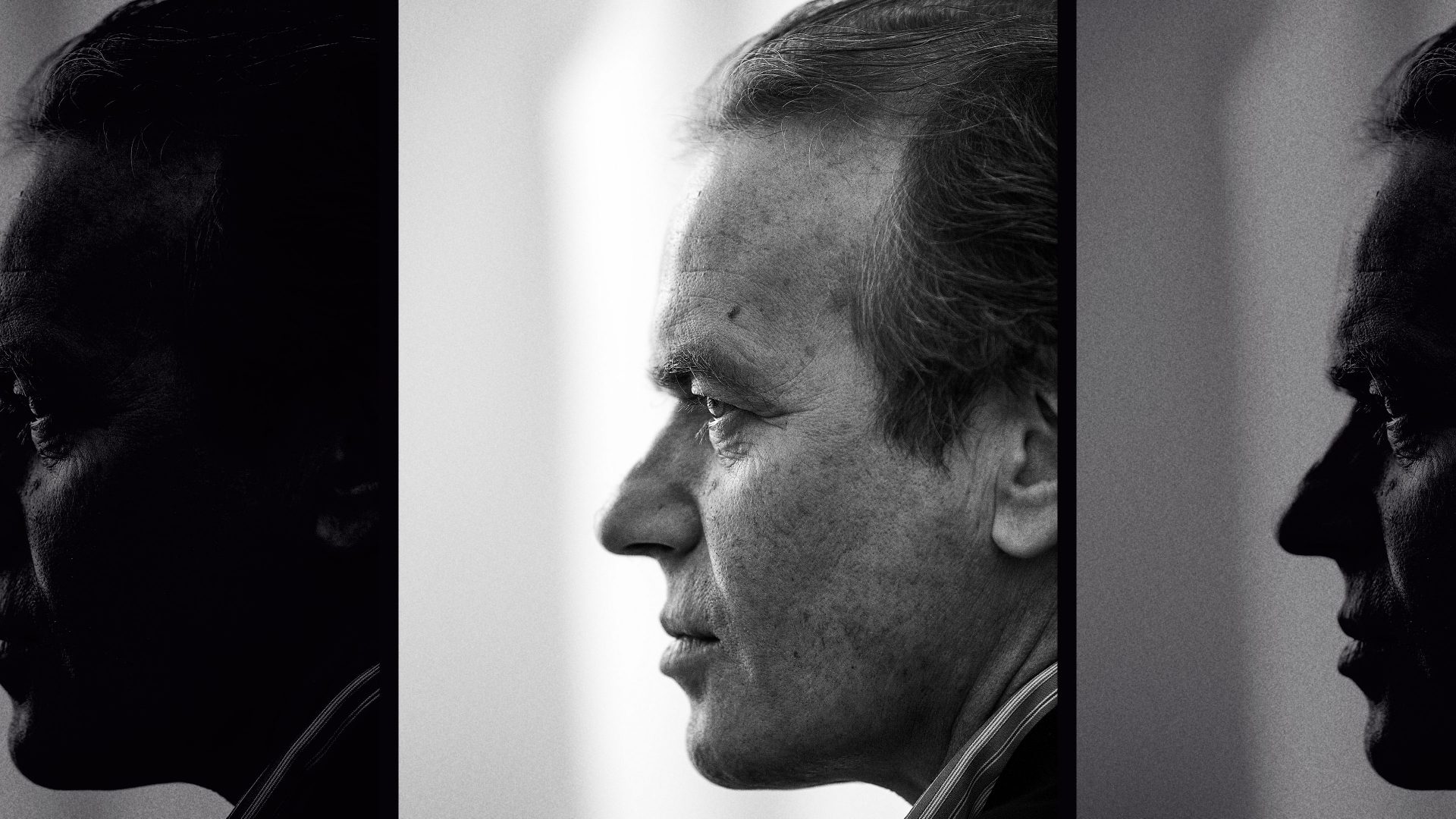

And what a movie. Killers of the Flower Moon is an epic, with Robert De Niro and Leonardo DiCaprio pulling out all the stops. I loved it. It’s not the director’s best film, but top 10 Scorsese is good enough for me. I preferred it to The Irishman, for example, and I thought that was pretty damn good.

Despite being made for Apple, this was roaring, old-fashioned cinema, a movie, a big movie on the biggest screen, with wide open spaces of America being exploited by venal, corrupt thugs murdering for money and to protect their own interests.

Based on a true story of mysterious murders amid the wealthy Osage Indian community of Oklahoma in the 1920s, it’s a tale I never knew, how these Native Americans were given a blasted plot of land (which was of course theirs by rights anyway) but struck oil and became the richest people in America. They had cars and white servants but were cruelly and systematically exploited.

Scorsese uses newsreels – some real, some digitally faked… you can’t be sure – to etch in American history. And then the drama takes over, a brilliantly scary De Niro pushing his lunk of a nephew (DiCaprio) to marry a local Indian woman (Lily Gladstone, outstanding) and have children so he can claim “headrights”, a legal loophole which means all her inheritance, all that oil money, will flow into white coffers, his coffers.

Rodrigo Prieto’s photography is crisp and rich and hauntingly beautiful and Robbie Roberston’s score delves into the American folk roots of blues, bluegrass and Indian chants. It’s a violent, weird, hallucinatory dream of a film, with a bitter edge of humour – De Niro in driving goggles looking like Toad of Toad Hall – and a shocking relevance today in its critique of the land-grabbing, greed of capitalism. Just writing about it has nudged it further up my Scorsese charts.

It’s a bit long, some people grumped. Really? How many hours of Succession do you watch (I like Succession, don’t get me wrong)? Surely you can stretch to 206 minutes of the greatest living American film-maker? It’s better than sitting in the rain. And, certainly better than watching Arsenal lose away.

Another marathon is the new documentary from Steve McQueen. So long indeed, that it came with a 15-minute interval. The director himself, taking to the stage in the Debussy Theatre where he announced his film-making talent to the world exactly 15 years ago with Hunger, acknowledged the length in his intro and pointed out the toilet facilities like a flight attendant, complete with hand gestures.

The film is Occupied City and occupied four hours of my life. What a wonderful four hours, though. I’m so glad I saw it. Everyone should see it.

Hardly anybody will, though, not at that length. There’s talk of a shorter version for release. I can’t see him bowing to such pressure, but it might not be his decision. There’s a lot of talk in Cannes.

McQueen tells the story of Amsterdam, the city where he’s lived for 27 years (you didn’t know that, did you?) and adapts what I imagine must be a brilliant book by his wife, Bianca Stitger, whose script and text here is one of the film’s masterstrokes. I’d recommend putting on the captioning or subtitles when you see it, because it’s like reading a dense and intelligent novel about the past at the same time as watching images of the present.

Occupied City is the story of Amsterdam’s capitulation to and collaboration with the Nazis and the city’s complicity in the extermination of its Jewish population. Narrated flatly yet chillingly by Melanie Hyams (I don’t know who she is, but her pronunciation of the countless Dutch and German names is spot on), the film unveils a scarcely believable history lesson of cleansing and murder, families killing themselves rather than facing living under Nazis, of deportations, humiliations, slow exclusions and otherings, a cold and calculated erosion of a people, 60,000 killings.

While the modern-day camera lingers outside an innocent-looking house, 6 Beethovenstraat, for example, the narration tells what happened to the people who used to live there. Extraordinary stories of cruelty and slow, systematic cleansing. In the end, the narrator just says: “He was taken into the dunes and shot.” Or: “His wife, brother and children were murdered in Auschwitz in 1942.” On the many spots where these gradual atrocities took place. It was once Jewish home or a shop. “Demolished” says the narrator as that story ends. Now there is a new building there, a gym or a dance studio or an office.

It’s such an extraordinary experience watching Occupied City. The present is in the foreground, images of Amsterdam in lockdown, its people going about their business, on demonstrations, facing off police, complying with rules (or not). And yet this present is also not the story as the history goes on underneath, in the background but also somehow in the foreground. There’s no archive, no artifacts of the past, no letters or photos – a genius way of showing how stories get erased, built over, forgotten.

Stitger has been on these pages before, her documentary Three Minutes: A Lengthening, about the discovery of a short piece of film about a Jewish ghetto town before the Nazis arrived, being one of my favourites of last year.

I don’t know what Occupied City is – art piece, installation, documentary, cinema, history. It is, certainly, a masterpiece.

There was a strange connection between Occupied City and Jonathan Glazer’s film The Zone of Interest. I say strange because Glazer tends to do films from another planet, works so unusual that they’re unlike anything else, ever: Sexy Beast, Under the Skin, Birth.

This is his first film in 10 years and, with uncanny timing, it premiered to huge expectation on the same day as Martin Amis’ death was announced, the author on whose book it is very loosely based.

It’s the story of Rudolf Höss (Christian Friedel) and his young family, all growing up and living in their nice house right next door to Auschwitz, where he is a fast-rising concentration camp commandant, impressing Hitler with his keen organisation and for hitting good numbers. The night sky is lit up outside their window with fires and the days are often cloudy with smoke from chimneys.

Told in stark black and white and all in German – Frau Höss is superbly played by Sandra Hüller, and Best Actress could be hers for a Lady Macbeth sort of role – there’s something of Michael Haneke’s The White Ribbon about it, with a smattering of McQueen’s Hunger and something of Ralph Fiennes’ Amon Göth in Schindler’s List.

These are all good things, as is another screeching Mica Levi score (she did Under the Skin) punctuating and grinding away.

There are superb shots and tableaux here, beautifully lensed East European countryside (fabulous cinematography from Lukasz Zal who did Ida and Cold War for Pawel Pawlikowski) all masking an infernal death machine, while Höss’s trip to the Concentration Camp Commander’s summit and ball

in Berlin is borderline genius, if it weren’t so horrific to contemplate.

And I guess that’s it. Glazer’s looking for a way to deal with how our horror at the Holocaust has been dampened, made banal, how it was just people doing their job, very well. If I’m honest, and of course I have to be, I thought it was all impressive but the film didn’t chill me or shock me or actually move me. That might have been the point, but it’s an odd point, because Glazer’s films usually take you somewhere extraordinary – which of course the Holocaust was, but it has now become ordinary. I hope I make sense.

Maybe the film will win the Palme d’Or and at this halfway stage, my head says it’s the film to beat and I think it would be a worthy winner.

I did wholly love Todd Haynes’ latest, May December, which features my favourite Natalie Portman performance in ages. She plays an ambitious actress researching a film role in which she’s about to play a “ripped from the tabloid headlines” true-life story, about a married Savannah housewife who had an affair – and child – with a seventh grader. I had to read the French subtitles to work out what that really meant, yes, he was 13, same year as my kid is in! First year of big school.

The lovers are now happily married and raising a very confused blended family. The older woman is played by Julianne Moore, as brilliantly as ever

when working with Todd Haynes (Far From Heaven remains a firm favourite).

This is a strange and delicious soap opera of a melodrama, funny and macabre and campy in parts as if Portman and Moore were Joan Crawford and Bette Davis, complete with crashing music score – it’s part of Michel Legrand’s music for Joseph Losey’s The Go-Between – at key moments, even when Moore opens the fridge and decides “We’re going to need more hot dogs.”

The festival’s opener could certainly have done with at least a scintilla of the tonal mastery of Haynes. Lord only knows what the French actress Maïwenn was going for, directing and starring in Jeanne du Barry, in which she plays France’s most famous courtesan, who seduced Louis XV and scandalised Versailles. Not only is Maïwenn unconvincing in the role, she had no chemistry with her co-star, the deliberately stunt-cast Johnny Depp.

Depp is, frankly, rubbish here. Not because he’s speaking French but because he looks smug and like he couldn’t give a shit about all the fuss around his recent court hearing which has, quite clearly, upset a lot of people. This was unserious, flippant, indulgent film-making, a waste of good wigs and gold leaf paint.

Cannes can do better – and thankfully it did.