At 6.27pm on June 11, 1955, during the third hour of racing at the 24 Hours of Le Mans, a Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR sports car smashed into the banking in front of a spectator enclosure. The car stopped dead and burst into flames but the engine block, gearbox and bonnet ripped free, ploughing onwards and scything through the dense crowd – 83 spectators were killed. It was the

worst accident in motor racing history. A priest who attended the dead and

dying said “I now know what hell looks like.”

The driver of the car also perished. At the subsequent inquiry, Frenchman Pierre Levegh was absolved of any blame – a slower Austin-Healey driven by British driver Lance Macklin had swerved across the front of him and his Mercedes struck its sloping rear, which acted as a ramp, launching it towards the spectator area, to devastating effect.

The cause of the accident was a problem as old as the Le Mans 24-hour race itself. One feature of long endurance races is that drivers in faster cars have to make split-second decisions when overtaking in order to minimise the time being stuck behind a slower car. Dive this way or that? Risk not being seen by the driver in front? Or play it safe and follow through the corners until an easy gap opens up on a straight section of track?

On that terrible afternoon in 1955, Levegh’s Mercedes team was up against Jaguar, their co-favourites for victory. Driving for the latter and leading the race was Mike Hawthorn, who three years later would become Britain’s first Formula 1 world champion. He was under pressure from another world champion driver, Argentine Juan Manuel Fangio in his Mercedes. Both had just lapped Levegh and were battling for the lead.

At Le Mans, cars are frequently entering and leaving the pits. To run for 24 hours fuel, tyres and, indeed, drivers need to be replenished and Hawthorn was due into the pits, located on the right-hand side of the track. But Macklin, up ahead, was unaware of Hawthorn’s intentions and pulled to the right to allow the train of faster cars to pass.

Hawthorn saw this but, not wanting to pull up behind Macklin, decided he had time to overtake the slower car before stopping at his pit. He passed Macklin on the left and immediately swung right across the front of the Austin-Healey towards his pit.

Macklin, startled, swerved left straight into the path of the lapped Levegh. Macklin recalled feeling the heat of Levegh’s exhaust as the Mercedes passed over his head. Fangio, realising he had no time to brake, dived between Hawthorn’s Jaguar and Macklin’s Austin-Healey, leaving paint on both.

Macklin’s damaged car slewed across the track into the pit wall and then came to a crumpled rest. Levegh’s car did not. Out of the corner of his eye, Hawthorne saw the car’s engine block and bonnet flying into the crowd “like a spinning top”.

Despite the death toll the race continued, the organisers probably correctly figuring the emergency services would be hampered by departing spectators. Hawthorn would go on to take the most soulless of victories.

Although the part he played in the tragedy was inadvertent and guiltless –

all drivers were exonerated – Levegh’s name is forever linked with that dreadful day almost seven decades ago. And the accident will perpetually

obscure what was (almost) one of the greatest drives ever seen at the 24-hour race three years earlier. As the 70th anniversary of the 1952 race approaches, maybe Levegh’s feat that year deserves to step out from the shadow of the catastrophe that claimed the lives of so many.

The 24 Hours of Le Mans was first run in 1923. In the early days of what is considered the world’s greatest – certainly most arduous – motor race, drivers attempted to complete the entire 24 hours by themselves. Nowadays the rules insist each car has three drivers sharing stints. The dangers of someone attempting to drive at speeds of up to 300km/h for a full 24 hours are obvious. The 6km, pedal-to-the-metal blast that was the Mulsanne straight was notorious – especially in the early morning hours – renowned for sending tiring drivers to sleep at the wheel.

Although many had attempted a solo drive, only Edward Ramsden Hall, a

Yorkshireman born into a wealthy textile mill-owning family, had succeeded. His career had begun before the second world war, in what was known as the era of the Bentley Boys – a group of wealthy, privately educated British drivers who had won Le Mans and other endurance races throughout the 1920s and 1930s in their eponymously named cars.

Some would change from racing overalls into dinner jackets as evening dawned at the 24-hour race and then continue driving throughout the night. All gentlemen amateurs, to them sport was something of a playboy adventure.

Hall also competed in Olympic bobsleigh and played university cricket. At Le Mans in 1950 he had entered a pre-war 4.3-litre Bentley S6 (a car by then 16 years old) and somehow dragged it into eighth place. Not once did he get out. When asked by journalist Denis Jenkinson “How?” Hall replied: “The key is to wear green overalls, dear boy”.

Pierre Levegh was not of similar stock. He was a Parisian garage owner; a serious, professional racing driver, not a dilettante racing for japes. His real surname was Bouillin but he took the name Levegh in tribute to his uncle who had raced – and died in – cars in the early part of the 20th century, but also so his mother would not know he too was risking his life in the manner her brother had.

He had already raced four times at Le Mans for the French-based factory Talbot team with a best-placed finish of fourth in 1951. The following year the Talbot cars were all entered privately as, after many fallow years, the factory had withdrawn official support. Levegh, by now, knew Talbot’s designs well. He spent weeks improving the car in his workshop and believed he knew it inside out. But funds were limited. Instead of a professional driver, Levegh was again paired with amateur René Marchand, with whom he had shared fourth at the previous year’s race.

Levegh wasn’t best pleased. He knew Marchand’s abilities were limited and he also knew any time Marchand spent in the car would be detrimental to his chances. He told nobody in advance, but decided he would not get out of the car once he’d climbed into it for the 4pm start on June 11. He was going to attempt to stay awake for the full race.

But, of course, it’s not just the 24 hours of competition. Drivers have to be awake in the morning as the car is being prepared, they have to eat sufficiently before the race starts, they have to fulfil the formalities of a racing driver even before they climb into the cockpit. And once there it’s not only a matter of staying awake for 24 hours (something difficult enough sitting in your front room watching Netflix with copious cups of coffee), it’s like concentrating for a 24-hour maths exam while simultaneously fighting a 24-hour wrestling match, and trying to avoid 59 other cars, all carrying drivers at varying levels of attentiveness.

When a human stays awake for so long, unsurprisingly they start to lose concentration, their short-term memory suffers, their judgment is impaired and they feel drowsy. More significantly it’s considered comparable to having a blood alcohol level of above 0.1% (or 100 milligrams of alcohol per 100 millilitres of blood). This is over the legal driving limit for the UK and most other nations. Consequently, coordination is impaired, muscles tense, stress rises and the risk of accidents increases exponentially. The brain compensates by entering a state known as “local sleep” – some neurons shut down and although the individual may appear awake, their ability to perform simple tasks declines significantly. And Levegh was 46, no spring chicken.

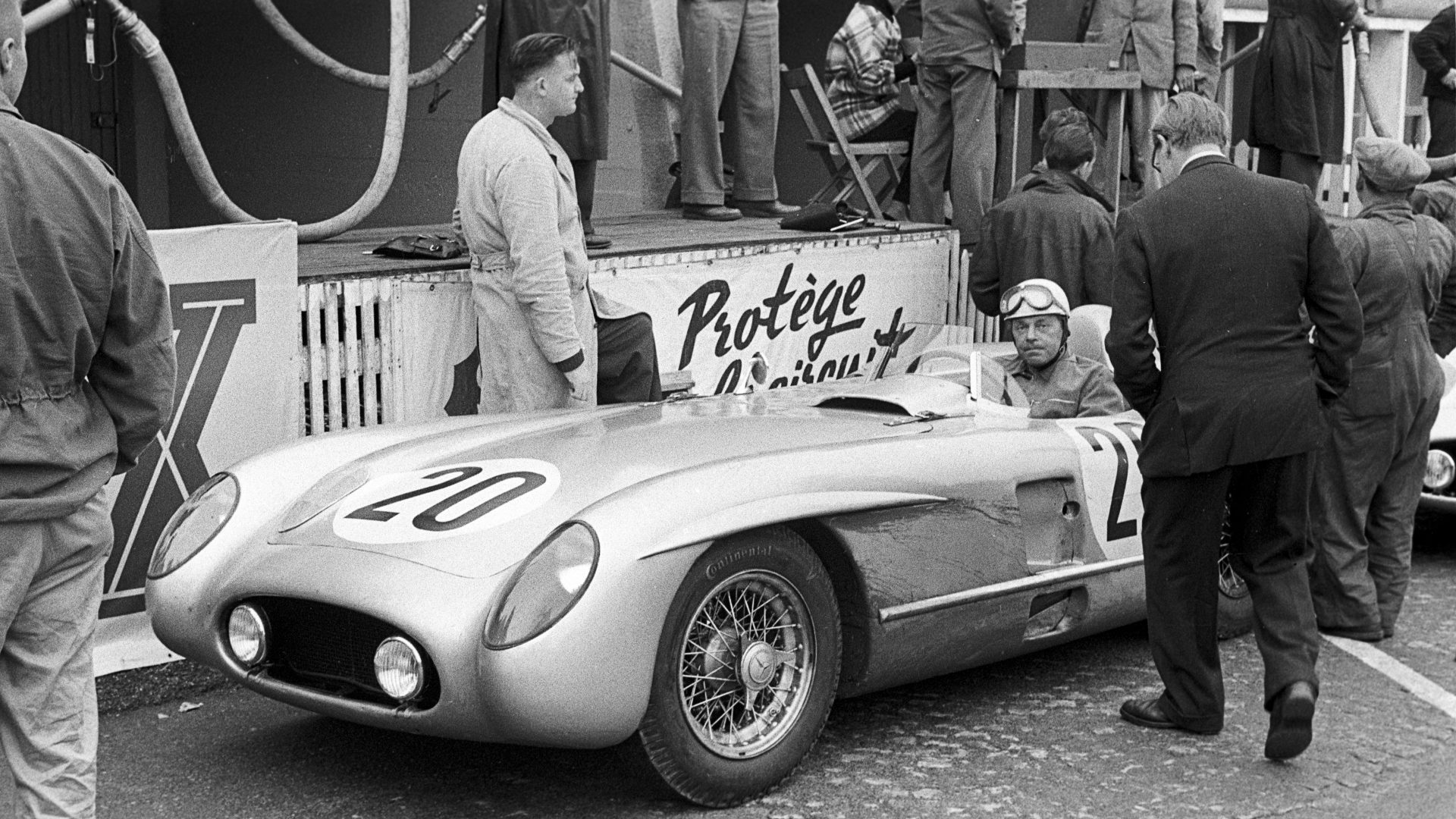

He was also up against three factory Mercedes entries, three C-type Jaguars

and six works Ferraris among the 60 entrants. Famed drivers Hermann Lang, Peter Collins and Karl Kling barred Levegh’s route to victory. Yet luck played into his hands. Jaguar, winners the previous year, had restyled its bodywork, attempting to streamline its cars for the long Mulsanne straight. However, this restricted airflow to the engines. All retired within three hours of the start due to overheating and shortly after half distance, only one of the

ill-prepared Ferraris remained. Star names Stirling Moss, Alberto Ascari and Luigi Villoresi, all Grand Prix winners, were gone.

Meanwhile, the strong Mercedes team debuting its 300SL sports coupes, which would subsequently enjoy great success, seemed oddly underpowered, running ninth, 10th and 11th in the early stages. All would be promoted by the demise of the Jaguars and Ferraris but ploughing on ahead of them was a Parisian in his privately entered Talbot.

Levegh had refused to vacate his car at the first pit stop – shouting lamely that its rev counter was broken and Marchand was too inexperienced to be

trusted without it – and it became apparent to his pit crew that he would not be getting out at all, not even for a comfort stop because he feared the team would put Marchand into the car. Later he would insist it was all a point of honour – he did not want Marchand to suffer the ignominy of retiring the car. What Marchand made of it we will never know, but onwards drove Levegh, eventually taking the lead when the Simca-Gordini of Robert Manzon and Jean Behra retired with brake failure.

With three hours left, Levegh led by an astonishing four laps (or 54km on the long Le Mans circuit). But his driving was becoming erratic. Twice he completely left the track, fortunately hitting nothing and rejoining. Foolish or brave? Whatever, it ended in failure.

The strain of driving more than 3,500km took its toll. With a mere 50 minutes of the race to run, Levegh selected first gear instead of third as he accelerated away from a slow corner. The crankshaft snapped. “France was cheated of victory,” wrote Anders Ditlev Clausager in his history of the race, although Levegh was in part the author of his own downfall, however glorious his failure.

Levegh had also failed to beat a record for the longest time behind the wheel for a winner of the race set in 1950 by French driver Louis Rosier. Rosier was also driving a Talbot with his son, Jean-Louis, as back-up driver. Unfortunately for the father who was hoping to drive the full 24 hours by himself, his gastrointestinal tract got the better of him. He’d been happy enough to urinate in his racing overalls, but defecation was one step too far. With only a couple of hours left to run he stepped from the car to allow Jean-Louis to drive two laps. His time in the car of 23 hours 40 minutes, however, will be a record that is never beaten.

The cautiously driven Mercedes strolled to a debut one-two driven by Hermann Lang and Fritz Riess, Theo Helfrich and Helmut Niedermayr. Wisely, they had shared the driving.

The following year the rules were changed. “The crazy antics of Levegh would be a thing of the past,” wrote motorsports historian Geoff Tibballs. No driver would be allowed to race more than 18 hours total or no more than 80 laps in a stint. The restrictions have become even more stringent down the years.

In 1955, fatigue played no part in what happened to Levegh and 83 spectators. The race was only two and a half hours old. But it decreed that the quite staggering feat three years earlier by a garage owner from Paris pretty much became a footnote to a tragedy. “It was epic,” wrote author Brian Laban. “A remarkable personal effort.”

Indeed it was. But for a missed gear change it might have been even more remarkable still.