“I am in bad humour, and sad, and the family can be glad they are away from me,” wrote Elisabeth, Empress of Austria, to her daughter the Archduchess Valerie in July 1898 from the German spa town of Bad Nauheim. “I have a sense that I will not rally again.”

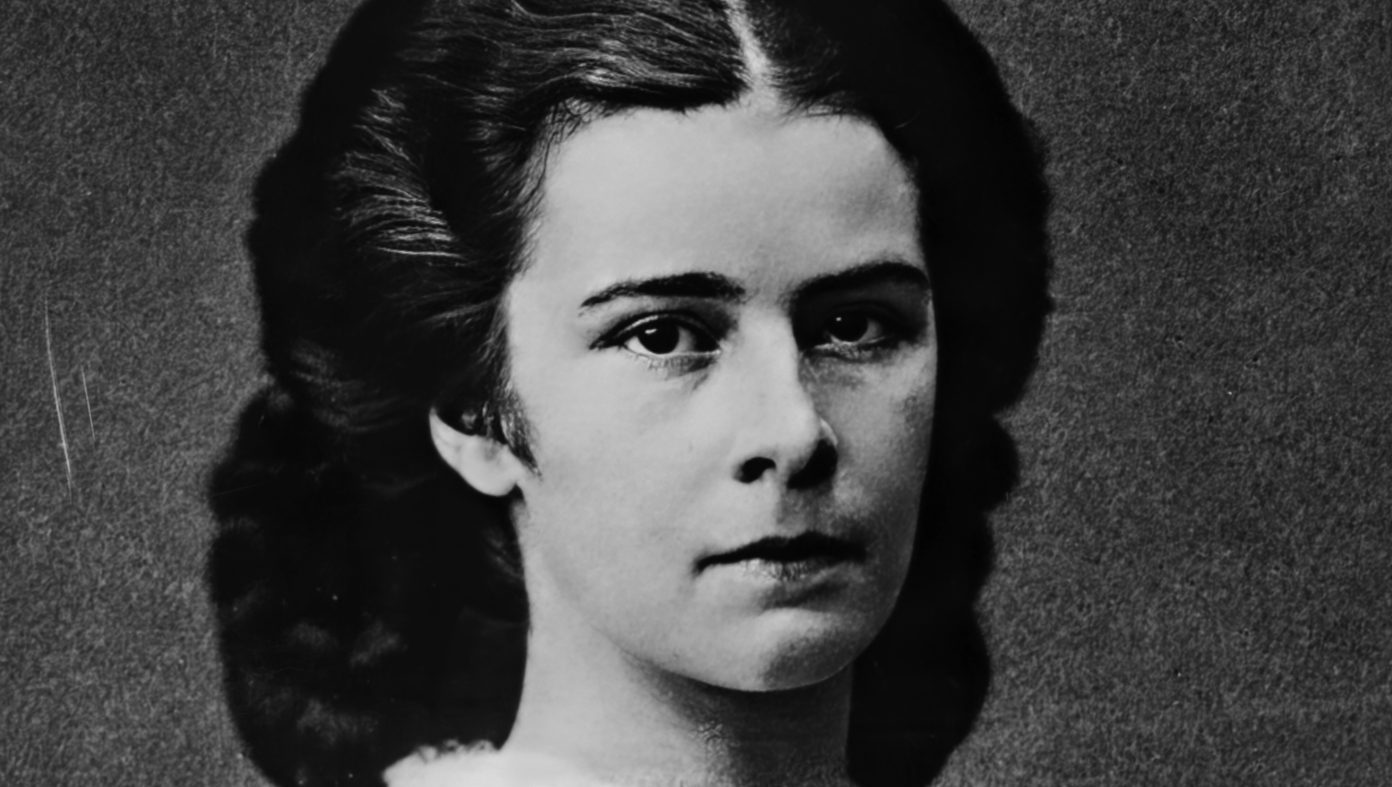

Feted as the most beautiful woman in Europe after her 1854 marriage to the Habsburg Emperor Franz-Josef, Elisabeth was in her 61st year when she wrote that letter, her famous eccentricities becoming tinged increasingly with melancholia as she aged. Her physical condition after decades of disordered eating and obsessive exercising was also of concern; in May Valerie had visited her mother on the French Rivieria and recorded in her journal: “Mama looks very ill, yet everyone here says she is better”.

Perennially restless, Elisabeth spent her later years shuttling between the spa towns and coastal resorts of Europe often accompanied only by a friend or lady-in-waiting. She had prohibited having her photograph taken when she was 30 and even stopped sitting for portraits a decade later, so travelling under pseudonyms meant she was usually able to enjoy the advantages of remaining incognito.

At an inn in Bad Ischl that summer, for example, she was recognised by a well-known actress of the day sitting alone after her companion had stepped out of the room. Elisabeth whipped out her dentures, held them over the edge of the table, rinsed them from a glass of water and replaced them in her mouth, something that went against every aspect of strict Habsburg etiquette.

In early September 1898 she alighted in Geneva, a city that always lifted her spirits, whose lake she found particularly restorative. “It is altogether the colour of the ocean,” wrote the woman who loved travelling by water so much she had a tattoo of an anchor on her shoulder. “Yes, altogether like the ocean.”

Elisabeth spent the day before her scheduled September 10 steamer departure for Montreux visiting her favourite patisserie and buying toys for her grandchildren before returning to the Hotel Beau-Rivage. As usual she was staying under an assumed name – the Countess of Hohenembs – but was irritated to learn that word had reached a Genevan newspaper that the Empress Elisabeth herself was in residence.

The news would create considerable interest in the city as Elisabeth had become one of Europe’s most enigmatic presences. While she fulfilled many duties at the Viennese court she had always forged an idiosyncratic path through imperial life, the stifling nature of a world fuelled by formality confining her to an existence entirely unsuited to her personality.

She wasn’t even supposed to have married Franz-Josef. In 1853 the then 15-year-old had travelled to Bad Ischl with her mother and older sister Helene to meet the emperor and receive his formal proposal of marriage to Helene. When the trio was presented at court, however, he was immediately smitten by Elisabeth and before long announced he wished to marry her instead or he would not marry at all.

Having enjoyed an unusually free and independent childhood where her aristocratic Bavarian parents indulged her compulsion to roam the countryside at will and allowed her to develop a passion for literature, philosophy and the arts, a bewildered Elisabeth knew life as the Habsburg Empress would be utterly stifling by comparison. According to contemporary accounts, when she left the marriage ceremony to be paraded in a golden coach through the packed streets of Vienna, Elisabeth was visibly distraught.

She attempted to control the one aspect of herself over which she was allowed some degree of influence: her appearance. Elisabeth became obsessed with reducing her waist size and never weighed more than 50kg. In her final years, other than the occasional Sachertorte, she existed on nothing but raw milk, oranges and eggs. Her daily hair regime took up to four hours and she was also a vigorous devotee of physical exercise, installing a gymnasium in each imperial residence that she used every day.

Elisabeth’s residence at the Beau-Rivage appeared in the Genevan newspapers on the morning of her departure. Among those who read the news was Luigi Lucheni, a member of the anarchist “Regicide Squad” who had arrived in Geneva planning to assassinate the visiting Prince Philippe, Duke of Orléans. When the prince changed his plans and went elsewhere, the Empress of Austria’s presence in the city presented a much better, higher-profile target.

The one consolation of Elisabeth’s role as empress was the opportunity to indulge her love of Hungary, occupied by Austria since the 1848 revolutions. She learned the language, filled her staff with Hungarians, visited as often as she could and became the crucial influence on the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 that turned Hungary from occupied nation to equal partner in an empire.

By then she had commenced her peripatetic ways after a severe mental health episode in 1862, confiding in her journal her wish to “travel the world over until I drown and am forgotten”.

Her itinerary became more frenetic after the 1889 murder-suicide of her only son Prince Rudolf and his lover Mary Vetsera at a hunting lodge at Mayerling, commencing a tragic decade in which she lost a string of close friends and family members. After Mayerling she was rarely seen wearing anything but mourning clothes.

Leaving the Beau-Rivage, her pace quickened as she saw the lake ahead of her and the steamer taking on coal. Accompanied by the Hungarian Countess Sztáray, when she hurried towards the landing stage a man bumped into her in the street, knocking her to the ground.

“What did that man want?” she asked after being helped to her feet. “Perhaps he wanted to take my watch?”

Unaware that the man, Luigi Lucheni, had stabbed her fatally in the heart with a file sharpened to a needle point, Elisabeth walked 100 metres to the landing stage and boarded the ship before collapsing. She died within minutes from a wound so small it was mistaken at first for an insect bite.

One of the first women of celebrity in the modern sense of the word, Elisabeth of Austria was a gifted, vibrant woman imprisoned by contemporary etiquette who spent her last years travelling the continent escaping her grief and searching for herself.

“Oh, had I but never left the path that would have led me to freedom,” she wrote in one of her many poems. “Oh, that on the broad avenues of vanity I had never wandered. I have awakened in a dungeon with chains on my hands.”