Maria Sibylla Merian confidently straddled the two worlds of art and science in the 17th century and her influence remains strongly felt today. Her colourful life passed through as many stages as the butterflies that she revealed to the world.

The German naturalist and pioneer enjoyed a successful career as an artist, botanist, naturalist and entomologist, but it was her revelation of the life cycle of insects, especially butterflies, that really brought her to the world’s attention as she unveiled the previously unknown process of metamorphosis.

Her ground-breaking contribution to her field came 150 years before Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution in On the Origin of Species hit the press. She also caught the attention of the Royal Academy more than 250 years before the first woman was permitted to join.

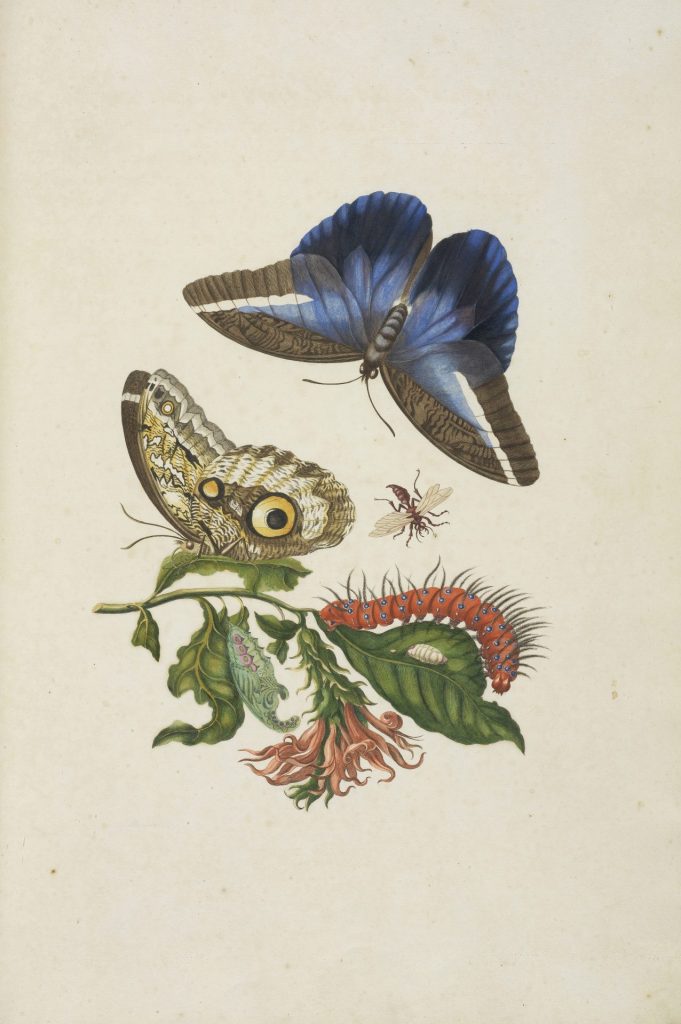

Her main life’s work, Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium, caused a sensation across Europe when it was first published in 1705, as her observations contradicted the popular theories of the time about how insects developed, especially the belief that they spontaneously emerged from mud, waste and plant matter in a process known as “spontaneous generation”.

At a time when natural history was a valuable tool for discovery, Merian uncovered a mass of new facts about plants and insects. The knowledge she collected over decades didn’t just satisfy those curious about nature but also provided valuable insights into medicine and science. She was the first to bring together insects and their habitats, including the food they ate, into a single work.

By any standards her achievements are remarkable, but for a woman in 17th‑century Europe she truly earned that often-overused title of trailblazer. The first European woman to venture solo into the Amazon rainforest on a scientific research expedition, she discovered unknown animals and insects in the interior of Suriname and her classification of butterflies and moths is still used today.

“Maria Sibylla Merian was a rising figure in the late 1600s, early 1700s, in times when women did not have a voice,” said Dr Blanca Huertas, a senior curator of lepidoptera at the Natural History Museum in London. “Her courage travelling to new worlds and her immense talent has been an inspiration to many scientists, artists and naturalists alike. She was a pioneer in beautifully combining science and art to make a wider impact on her works, such as Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium, which has been translated into several languages.”

Born in Frankfurt to a family of Swiss origin, she was interested in flowers and insects from an early age. She collected butterflies and caterpillars and raised silkworms to study their life cycles.

After the death of her father, her mother married influential still life artist Jacob Marel who recognised the talent of his stepdaughter and encouraged her. At 13, Merian created her first drawings and watercolour paintings. She became a prolific painter of European insects and plants, reproducing the images from specimens she had captured in different stages of their life. She continued her research and observed how caterpillars pupated themselves and how the most beautiful butterflies and moths burst out of their colourless cocoons.

Aged 18 she married, and she and her husband, cityscape artist Johann Andreas Graff, moved to his home town of Nuremberg where she published her early illustrated botanical art books. Later she published her first work on insects, the first of two volumes focusing on metamorphosis.

Trading ships brought back never-seen-before shells, plants and animals, but Merian was not interested in collecting or studying preserved specimens. In a radical break from the convention of the time, she collected, raised and observed living insects. She was one of the first European naturalists to work in this way and recorded and illustrated the life cycles of at least 186 different species.

Her marriage was an unhappy one and in 1685, controversially, she fled with her mother and two daughters to the Dutch province of Friesland to an austere Protestant commune, the Labadists. She lived in a castle owned by Cornelis van Sommelsdijk, the first governor of Suriname, and so began her lifelong attachment to the tropical flora and fauna of this South American nation.

When her husband followed her, the Labadists declared that she was free from all marital obligations to a nonbeliever, so he returned to Nuremberg to finalise their divorce.

In 1691 she moved with her daughters to Amsterdam when it was at the very centre of the Dutch Golden Age, a hub for science, art and trade. Merian was a savvy businesswoman and, under the city’s relatively progressive laws, was able to open her own studio and work as an independent artist. She became an important figure among the city’s botanists, scientists and collectors. Her caterpillar books were also getting noticed among the scientific community in England.

Her eldest daughter, Johanna Helena, married a merchant, Jacob Herolt, who traded with the new Dutch colony of Suriname and the couple relocated there. Inspired by Johanna’s descriptions of her fascinating new home country and the cosmopolitan influences around Merian, her ideas for her own voyage of discovery began to take shape.

After eight years of preparation and fundraising, at the age of 52 she set off on her trailblazing trip to the Amazon, which would provide so much of her research material. Her trip was partly sponsored by influential figures from Amsterdam but, unusually for the time, it was mostly self-funded from the sale of over 200 of her own botanical illustrations. In 1699 she sailed nearly 5,000 perilous miles from the Netherlands to South America with her youngest daughter. It was the first ever purely scientific expedition to the Dutch colony. For two years they travelled around the jungles of what is now known as Suriname, French Guiana and Guyana.

She drew heavily on the local knowledge and assistance of enslaved people, who laboured in terrible conditions on the Dutch sugar plantations, and her book contained candid accounts of their hardship. Her independent funding gave her the freedom to criticise the colonial merchants for their treatment of slaves in Suriname and their reluctance to show any interest in indigenous crops as they focused solely on sugar exports.

She had planned to stay five years, but was forced to cut short the trip and return to Amsterdam in 1701 after becoming ill. She opened a shop selling the specimens she had collected and started on her great work.

Years of careful observation enabled her to create stunning visuals and stories of plants, insects, amphibians and reptiles from a land that most people at the time back in Europe could only imagine. She was among the first to showcase the little-known pineapple. For the first time Merian documented the metamorphosis of tropical butterflies from pupae to caterpillar and into adulthood.

She received much acclaim in Europe as she revealed a side of nature so exotic, dramatic and valuable to botanists of the time. Her paintings inspired artists and ecologists alike and her discoveries and insights are still influencing biology today.

“Merian was an original,” writes Amanda Vickery, professor of early modern history at Queen Mary University of London. “She intrigues scholars but hers is hardly a household name. The hybrid quality of her work as a naturalist has hindered her posthumous reputation.”

“In her time, Merian was prized for her contribution to entomology. Today, it’s her fusion of artistic efforts and scientific observations and the way in which her paintings defied Victorian categorisation that make her so fascinating. She is acclaimed as one of the greatest artist‑naturalists of her time.”

In 1711 Merian suffered a stroke and died in Amsterdam six years later. That same year her daughter published for the first time all three parts of her mother’s life’s work under the title Erucarum Ortus, Alimentum et Paradoxa Metamorphosis, dedicating it to her mother.

Shortly before her death, many of her paintings were seen by Peter the Great during a visit to Amsterdam. After she died he acquired a large number of them. Upon his death, the works were presented to the Academy of Science in St Petersburg, where they remain.

Over the years her illustrations have become extremely popular and are held by many prestigious collections including the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle.

A renewed scientific and artistic interest in her work was triggered in part by a number of scholars who re-examined collections of her works, such as the one in Rosenborg Castle, Copenhagen. In 2016, the Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium was re-published with updated scientific descriptions.

Maria Sibylla Merian might not be as well known as Darwin, but she was hugely talented and her place in the annals of natural history has been cemented thanks to a bevy of creatures including butterflies, moths, spiders, toads, birds, a lizard and a snail bearing her name proudly into the future. Her paintings are a fitting monument to such a unique figure whose life, too, was a blaze of colour.