You may have noticed that a lot of people, brands, and even heads of state have been posting Japanese animation-style images on social media recently, that mimic the famous Studio Ghibli look. That is because last month, OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT, released an update of its image generator. While many users apparently did not seem to think twice before sharing Ghibli-fied versions of their personal photos, others including myself, were left deeply unsettled by this new wave of so-called AI art.

In a 2016 video that is making the rounds again, Ghibli co-founder Hayao Miyazaki calls an AI generated clip “an insult to life itself.” It makes sense that an artist who has built his career creating sumptuous hand-drawn animated films, would not be thrilled about machines designed to generate images with barely any human input. And, as many have pointed out, he would almost certainly disapprove even more of this new machine churning out cheap approximations of his signature style as quickly as internet users can type a simple prompt.

I can already hear the tech bros calling me a luddite. Admittedly, it is not the first time that a new mode of image production has been criticised by sceptics – photography was first seen as a lowly replication mechanism before being accepted as a true art form – and it is certainly not the first time that a new technology has prioritised automation and efficiency over skill and artistry. But unlike irrational techno-fears – like the 19th century belief that telephones were conduits for evil spirits or the more recent conspiracy theory that 5G technology causes Covid-19 – the backlash against generative AI is grounded in very real concerns.

There are also concerns that AI is contributing to the disinformation crisis

AI models are trained on huge amounts of data, much of which is taken from uncredited copyrighted material. In 2024, thousands of creatives including musician Thom Yorke, actress Julianne Moore, and Nobel Prize-winning author Kazuo Ishiguro signed a statement saying that “the unlicensed use of creative works for training generative AI is a major, unjust threat to the livelihoods of the people behind those works, and must not be permitted.” There are also concerns that AI is contributing to the disinformation crisis, as AI models frequently “hallucinate” false information when used as a search engine, and they can also be used to create deepfakes to deliberately mislead people. And there is, of course, the not-so-small matter of the huge environmental impact of generative AI whose demand for electricity and water is astounding.

Even if it were possible to put these concerns aside – which, to be clear, we shouldn’t – it would still be difficult to shake the sense of unease that AI-generated images elicit. While I firmly believe it would be a waste of time to enter into pseudo-philosophical debates about whether AI-generated images can ever truly be considered art – any definition of what art is or should be is merely an open invitation to be challenged – it does seem worth exploring why, for so many of us, the idea of a creative machine feels so wrong.

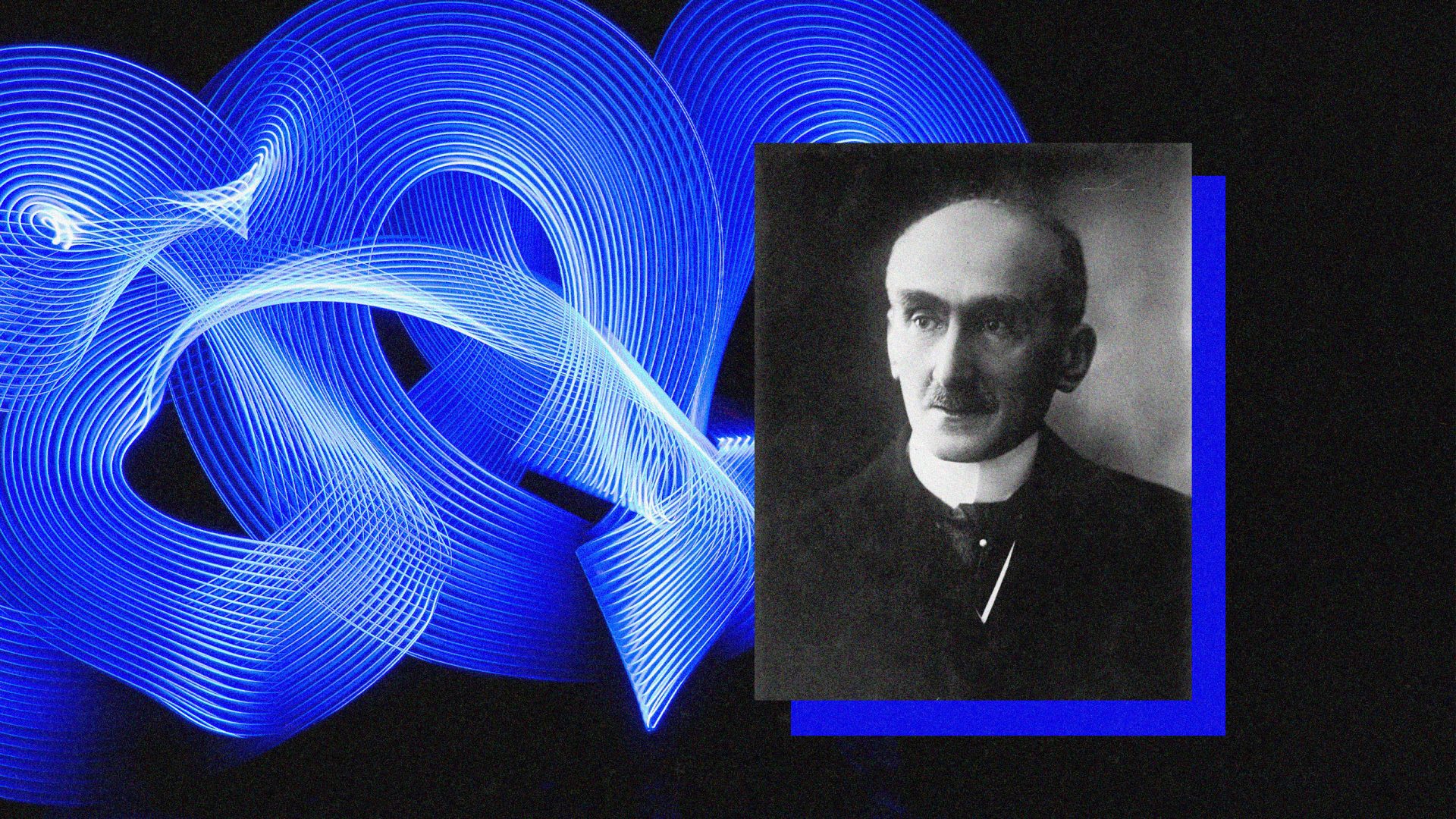

Before Alan Turing was even born, a French philosopher called Henri Bergson spent a lot of time thinking about creativity. He described life, and by extension our minds, as ever-changing, open-ended, creative, processes. Generative AI systems are trained on pre-existing data which is broken down into parts, and remixed based on patterns, algorithms and the probabilistic calculation of what the user is most likely to want. These models can only generate variations and permutations of what they have been fed, and are constrained by predefined parameters. If such a technology had been around in Bergson’s day, he would have said that this has nothing to do with creativity. For Bergson, creation is not a synthesis of pre-existing elements, but a truly unpredictable process of maturation that produces something completely new.

In the early 20th century, Bergson was a prominent critic of the idea that life and mind could be reduced to cold mechanical processes. But he understood why it was so tempting to do so. There are aspects of our intellect, such as pattern recognition and our ability to generalise and to classify, that seem quite mechanical. Similarly, when we are occupied with the practical demands of everyday life, we conform to norms and habits that function as sets of rules that dictate our behaviour, and when we engage in small talk, we often speak in clichés choosing from a large selection of pre-existing ready-made phrases. But Bergson’s point is that none of this even scratches the surface of our mind. If we try to fit consciousness into a machine framework, we end up focusing only on the mechanical aspects of the mind and completely miss everything else. AI enthusiasts argue that these new technologies open up new possibilities for creativity, but, if we follow Bergson, it seems that their models actually emulate the least creative aspects of our minds.

Beneath the surface of our predictable more mechanical self, lives what Bergson calls our fundamental self. It is there that our inner life takes on its own unique colouring, which no concept or algorithm can adequately capture or replicate. And it is from there that true creativity can “spring forth” as “an original and unique emotion”. For Bergson, human creativity is an intimate process of maturation driven by effort from which we can derive a sense of fulfilment – not merely the pleasure of being admired or recognised, but the joy of having participated in the act of creation.

This is why so many of us, like Miyazaki, have a knee-jerk aversion to generative AI. It effectively robs us of the joy of one of the most meaningful human experiences: the creative process itself.