Accompanied by Bridgit Mendler’s Hurricane and the familiar grinding sounds of an espresso machine, James Conway slid a small matte black book across the coffee table. “Have you got a copy of this? If you don’t, you should,” he said. It was Else Lasker-Schüler’s literary collection Three Prose Works, translated by Conway and printed by his publishing house Rixdorf Editions.

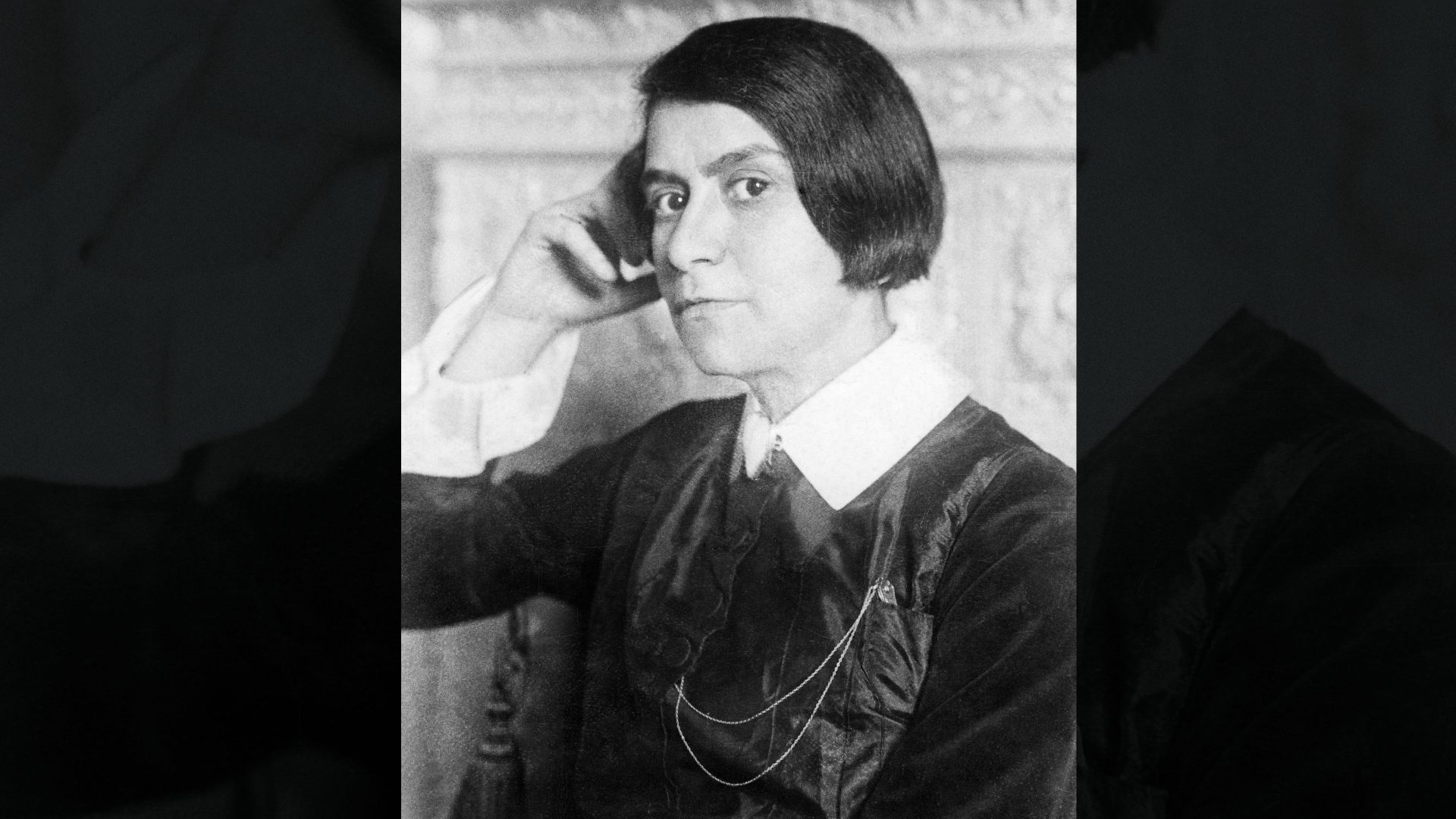

Else was a Jewish German poet, novelist and playwright. She was famous for her bohemian lifestyle and was a leading figure, and one of the only women, in the Expressionist movement. Joseph Goebbels called her a degenerate, Franz Kafka couldn’t stand her, and Karl Kraus was one of her biggest supporters. To me, she was family – my great-great-great aunt.

In 1939, my great-grandmother, Meta Schüler, knew her family had to leave Nazi Germany. After being denied entry to America the year before, plans were made to migrate to Britain and, as she was only granted a visa for one child, she made the journey from Germany to Britain five times, transporting a different one of her children on each trip. Her other sons and daughters who could not make the journey were left with people she trusted in Britain and Germany.

While Meta belonged to the Lutheran church, her husband Lutz – my great-grandfather – was Jewish, and their lives in Cottbus near the Polish border had become extremely dangerous. Lutz was a journalist, editing daily newspapers in Cologne, Forst and, eventually, the town of Cottbus where he met and married Meta.

In 1934, the offices where he worked were burned to the ground for printing anti-Hitler articles and in the same year, his brother, my great-great-uncle Hans, was arrested in Constance and died at the hands of the Gestapo in a Nazi prison. In 1939, they arrived at the Schüler family home and arrested Lutz, as my grandmother Susanne watched. It would be the last time she saw her father in Germany. She was seven years old.

In 2011, Susanne presented our family with a memoir of her childhood. In it, she recalled how, on a bitterly cold night, her mother took her and her four siblings to say goodbye to their father in prison. The children were instructed to wait across the street while my great-grandmother spoke to the guard, who agreed to tell Lutz to look out of his cell window. The room lit up, a moment passed and the light went out again. For reasons we don’t understand, he never appeared and Meta took five crying children home.

“I knew something was terribly wrong,” my grandmother wrote in her memoir. “Perhaps if I kept very quiet, no one would make me go to England?” In another chapter, she wrote: “I didn’t even know who Hitler was, just that I hated him with all my heart”.

Two years ago, my grandmother passed away. Since then I have been driven to uncover her and her family’s path to Britain. And that led me to Else.

Else Lasker-Schüler was born in 1869 in the Prussian Rhineland town of Elberfeld, the youngest of six in a Jewish family. Her father, Aron, was a banker, known prankster and related to the famous Prague Rabbi Judah Loew, creator of the Golem legend, told to Jewish children. Despite this, Else rarely spoke of her father with any great affection, saying he was “simply worried about his dahlias”.

Her mother, Jeannette, meanwhile, was “her idol”, who instilled a love of storytelling in her daughter. “She was the real poet,” Else once said of her mother.

In 1894, Else married Berthold Lasker, a doctor and renowned chess enthusiast, and they moved to Berlin. “Lasker certainly got more than he bargained for with the marriage,” Conway explained when we spoke in a cafe in the heart of Alexanderplatz. Else equated the domestic sphere to a “tomb”, frequently took lovers and in 1899, she gave birth to her illegitimate son, Paul. Lasker likely knew that he was not his biological son and Else never named the father, Conway says. Rumours of a Greek king or Spanish prince have never been confirmed.

In 1899 Else wrote the poem Wilted Myrtle, which directly addressed her relationship with Lasker. She wrote: “You trampled my young spirit dead / And then drew back inside your own cold shell”. This frosty work was the piece that began her literary ascent, appearing in the August issue of Die Gesellschaft. It was also that summer when she met the writer and occasional vagabond, Peter Hille.

Hille was her ticket to bohemian Berlin. He introduced her to the city’s hedonistic cabaret scene and artistic community, many of whom frequented the Café des Westens, which earned it the nickname of Café Größenwahn (Café Megalomania). In 1902, Else published her debut poetry collection, Styx and, three years later, another, entitled The Seventh Day. Both collections are filled with outlandish love poems. But the journey into bohemian society was not without cost – she and Lasker divorced in 1903.

As the Nazi menace began to rear its head, Else might have attempted to assimilate. She rejected the premise entirely, taking on an identity that she referred to as “the wild Jew”, a theme that comes up in her writing. “At the time, a common insult aimed at Jews was that they were oriental,” said Conway, “and it’s as if she said: ‘well, if you call me an oriental, I’m going to be an oriental.’”

“Everything about her was almost designed to antagonise the Nazis. She was an independent woman, she was a single mother and an associate of homosexuals. And, of course, she was Jewish,” said Conway. Except, she wasn’t just a Jew, she was an outspoken Jew. In 1930, she joined protests in Berlin when Nazi thugs tried to prevent the screening of All Quiet on the Western Front.

By 1932, she was at the height of her career, winning the prestigious German literary accolade, the Kleist Prize. Yet, with success came a much higher profile, and, for Else, danger. “It brought her to the attention of Goebbels who wrote offensively about her and called her a degenerate,” said Conway. In April 1933, the same year Hitler rose to power, she was attacked outside her hotel by a Nazi stormtrooper and the next month, students burned her books outside the Berlin State Opera. It was time to leave Germany.

With the help of benefactors, she fled first to Zürich where she relied on the support of the Jewish community to help pay her rent. In March 1939, thanks to financial support from her publisher, she settled in Jerusalem.

It was in Jerusalem that Else wrote her most famous work, My Blue Piano. It’s a poem about homesickness, a lack of belonging – and it reminded me of my grandmother, Susanne. In her memoir, she recalled how the two war widows she was living with offered her buttered toast, marmalade and tea for breakfast and on her bed, a fresh set of traditional English children’s clothes awaited her when she was ready to get dressed. She refused the food and wouldn’t wear the clothes. A few months later on her eighth birthday, she wrote how she feared that her mother, and Germany, had forgotten her.

In My Blue Piano, Else wrote: “Back home I have a blue piano. Yet I can’t play a single note… Now the rats dance to the clattering”. The piece is written in response to the violence that started to break out in her home town of Elberfeld as Jews began to be deported. Despite being the site of her professional fame, Berlin was never her home and now, far away from Germany, she longed for home. Her rats dancing amid the rubble were Nazis.

Meeting Else posthumously, my mind goes to my late grandmother. After she passed away, we found sheets of poetry among her belongings, all written in German. Subconsciously or not, Else’s legacy is evident in our family – but what of it elsewhere?

I recently went looking for Else’s Berlin, to see what was left of it. Café des Westens did not survive the war and while it briefly became Café Kranzler after 1945, today it’s a Superdry (“slightly less romantic,” laughed Conway).

However, in the Schöneberg district, parts of Else live on. In 1998 a section of Motszstrasse was named after her and today, Else Lasker-Schüler Strasse sits right outside the Nollendorfplatz U-Bahn station. Halfway down the street, a playground invites children into her literary mind. There are dragon slides and swings formed out of the other mythical creatures that appear in her writing. The iron cladding and vast security measures around the perimeter are less poetic.

Tucked away down a quiet side street sits Hotel Sachsenhof, where, according to a plaque, Else lived from 1924 to 1933. Not only has it survived, but today it’s painted hot pink. Inside, I asked the receptionist if it was possible to see Else’s room but, sadly, due to renovations and historical debates over which wing of the top floor she lived in, it couldn’t be done.

Two doors down from the hotel is the Magnus Apotheke, named after Magnus Hirschfeld, the German physician, early LGBTQ activist and author of The Third Sex. The pair were close friends throughout their time in Berlin, and in most of their correspondence Else addressed him as “Father Confessor”. The pharmacy’s display windows are filled with anti-ageing creams, hair dye and protein powders. Above the pharmacy, pride flags fly outside apartment windows.

The colloquial expression tells us that well-behaved women seldom make history and Else was far from genteel. Why then, has a poet so successful in her time failed to achieve the same profile as some of her contemporaries? Conway thinks it’s all to do with timing.

“She was very productive in the period before the first world war but she wasn’t translated into English to any great extent until after the second world war,” he explained. Else’s translated work, therefore, emerged in the postwar era, at a time when there was a resistance to German ideas and influence.

“Each generation still discovers something unique about Else,” said Conway. Perhaps that’s the key to her legacy. After all, her writing was defined by love, hurt and escapism and as motifs, like the poet herself, they’re timeless.

Still, for me, I saw her legacy growing up. My grandmother’s storytelling, creativity and defiance all had echoes of Else – which was, after all, her middle name.