Too often, when we talk about Elon Musk, we are really only talking about Twitter – and while the social network might feel like the centre of all things to those of us still hopelessly (and harmfully) addicted to it, in reality it is quite a peripheral thing.

Twitter was a minnow of a social network even before the Musk takeover, exceeded in size by Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, LinkedIn, Telegram and others.

While the potential for the social network to disrupt elections and foment extremism is indeed a serious issue, and one that must be faced urgently, to focus solely or even mainly on Twitter (or “X” as it is now called) is to risk missing the staggering extent of Musk’s political and economic power.

Musk is often cited as the richest man in the world (the top few bounce around slightly as stock prices shift), and is worth just under a quarter of a trillion dollars – enough money to spend $1m a minute every minute for the next 25 years and still not run out. His financial clout alone rivals that of some nations.

But wealth does not explain Musk’s influence. He is heavily involved in strategic industries, too. Tesla has made significant advances in battery technology as well as in self-driving software. Musk has multiple AI ventures, and with his Neuralink startup is trying to create technology combining man and machine.

But it is in the space sector where Musk has the most clout. It is indisputable that SpaceX now has the most advanced rocketry technology on the planet, more sophisticated than any government space agency. On its own, it controls an overwhelming majority of the planet’s launch capacity. If you want to put a satellite into space, you probably need Musk.

This is compounded by the sheer scale of his other space venture, Starlink, which provides satellite internet to remote locations through clusters of thousands of fast-moving communication satellites. Starlink has so many satellites that Musk controls more satellites in Earth’s orbit than every world government put together.

If space is indeed humanity’s future, it is currently in Musk’s hands. Even in the more prosaic everyday world, he is an unavoidable fact of life in multiple strategically important industries. Musk wields power on a scale that no individual – except national dictators – has held since the days of John D Rockefeller and Standard Oil.

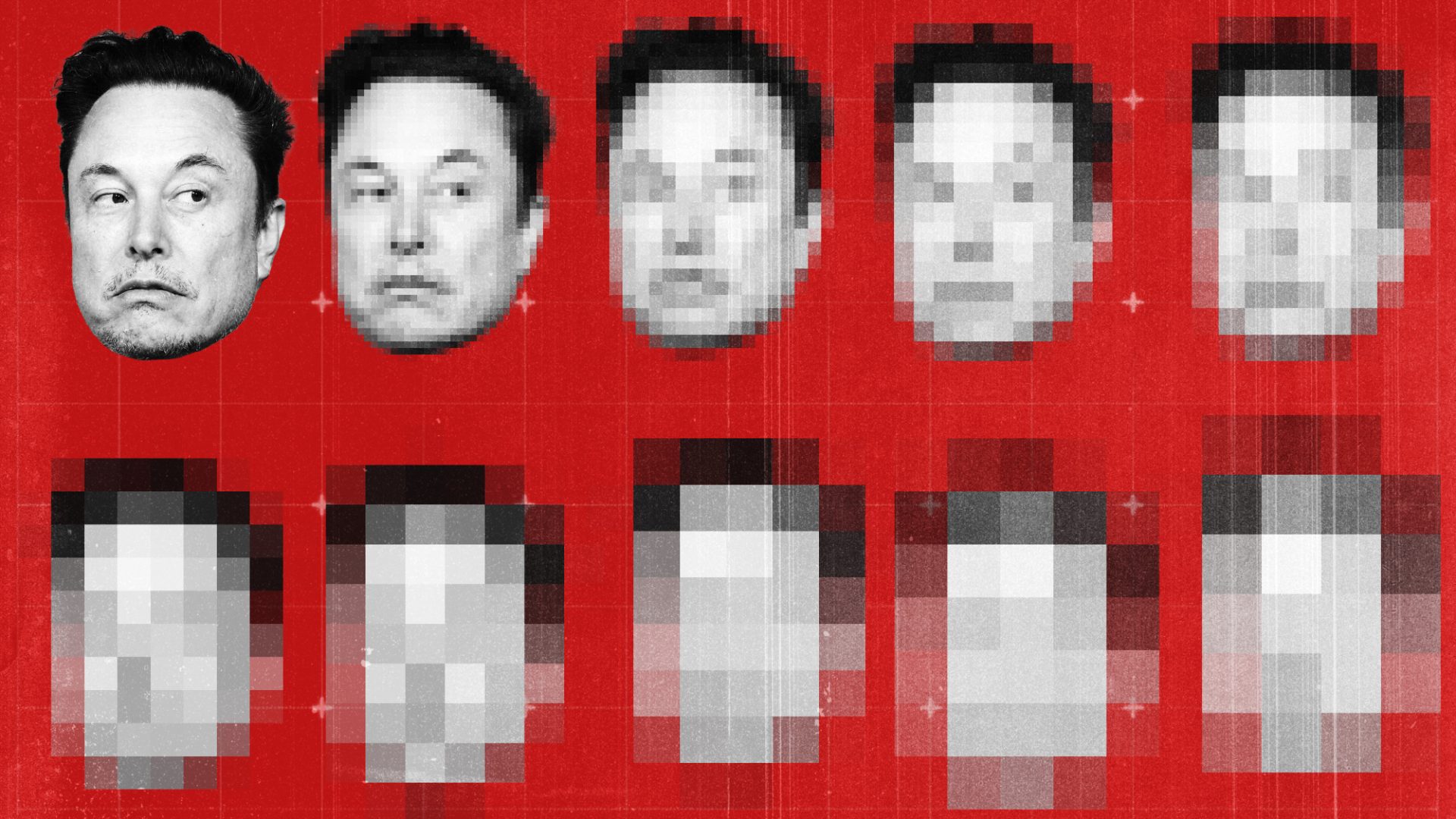

The temptation, given the very real power Musk does wield, is to portray him as a Bond villain, a super-genius beyond the abilities of mortal man – perhaps malign, but indisputably brilliant. Musk himself does nothing to disabuse such notions, and often outright encourages them. This is not a picture he is unhappy with.

In reality, the situation is more complex. Musk’s business career started with failure, which turned into success thanks to a series of huge gambles that happened to pay off. These were not simple cases of Musk being a visionary who was ahead of his time – at many key moments in the Musk story, had a factor outside his control gone just slightly differently, he would be just another start-up founder now worth $10m, maybe $50m, whom no one has ever heard of.

One of Musk’s quirks is that he has been known to wonder out loud whether we live in a simulated universe – perhaps a science experiment in a lab somewhere, or even in a video game. To think of Musk in those terms, in 99 out of 100 universes Musk would not be a household name. We just happen to live in the one where his bets came off and he is famous.

That does nothing to diminish the huge personal power he wields – control over strategic industries that could determine the future of our species, outright ownership of the social network most closely tied to the global information ecosystem, and near-unlimited wealth.

But absent the idea that he must be a world-level, infallible genius to get there, that power is if anything scarier: Musk is clearly a gifted man, but he is just a man, and his blind spots have become bigger and more dangerous as he has surrounded himself with sycophants. What if the man in charge doesn’t have a plan – sinister or otherwise – after all, and is just blundering through, like the biggest overgrown toddler of all time?

Musk’s business story is the stuff

of multiple books, including a dubiously shallow biography by Walter Isaacson. But Musk’s actual business story features less invention on his part than he likes to suggest with his own public image. Musk started out in the payments business. In the early 2000s he was running an early rival to the company that became PayPal – called “X”.

PayPal, which was founded by a group of libertarian tech execs including Peter Thiel (who later founded the surveillance tech company Palantir) was based in the same building as Musk, and both companies were struggling to attract enough funding to stay afloat – so they merged, with Musk becoming chief executive.

Musk was soon ousted as CEO in a boardroom coup organised by Thiel, because of his insistence that the newly merged company needed to dump the consumer-friendly (and banker-friendly) name “PayPal” for its product, and instead use his preferred brand name, “X”.

At the time, that name triggered red flag alerts with the banking system, which identified it as a pornographic site. Musk was quickly out of a job, but with millions in his pocket to spend or invest.

He soon found a promising prospect – a company called Tesla, founded in 2003 by the engineers Martin Eberhard and Marc Tarpenning. The two men had hit upon almost the exact formula that eventually propelled Tesla to its stratospheric success.

The first truly breakthrough product for an electric car would be aimed at car enthusiasts who wanted a top-end sports car, and who did not want to compromise on performance or style for a “green” car. The sales of that top-end luxury model could be used to finance the development of a lower-cost, mass-market electric car that would then supplant its petrol-engine rivals. The core ideas that made Tesla were theirs. Musk invested in the company in 2004.

Three years later, he made his move – not least because he was furious at being (accurately) described as an investor in the company rather than a founder – and ousted both Eberhard and Tarpenning. Soon after, the Roadster they had spent years perfecting hit production, with Musk (who had won the right to be called a “co-founder” in the subsequent lawsuits) serving as its face.

Tesla has always struggled to live up to its early promise: Musk has consistently promised that the self-driving car was imminent, but he is yet to deliver. Manufacturing scaled up far more slowly than he hoped. Tesla has been slow to refresh its range and offer up new models that compete with its rivals. The Tesla pick-up, the “Cybertruck” model, has been widely panned.

Tesla sells fewer cars than almost any big car manufacturer you can name, but is worth more than all of them put together, thanks to the belief retail investors have in Musk.

The danger to Musk is that the bubble of his myth pops before he has cashed out – a significant majority of Musk’s wealth is still inevitably tied up with Tesla – and that is a high point of weakness.

SpaceX is a similar story of an investor who came to rule the roost, though Musk has an even stronger claim here to say he was willing to take huge risks that almost no one else would. His entire space project came within days of bankrupting potentially both of his companies and perhaps even himself, as he sought to get a working launch rocket after two early explosions.

Musk would also like to be credited with the actual engineering breakthroughs that helped to build the best reusable rocket system on the planet. But the record on that is mixed – it is well known to Musk’s inner team that he needs to take the credit for such things. So (according to some biographers of his companies) his team let him believe just that, telling him “he” provided the breakthrough for problems someone else had already solved.

Musk has an ability to wring more out of his workers than almost anyone else on earth, to set impossible deadlines and push people to achieve them, and this, coupled with his willingness to take gambles that almost no one else would dream of, has propelled him to unimaginable success.

But none of that makes him superhuman or immune to human frailties. The Musk of 2024 is paranoid and credulous, routinely sharing the most ridiculous and racist of conspiracy theories online. He is ever-more obsessed with his “enemies”, and disdainful of anyone who would try to point out that the rules also apply to him.

Musk is not a Bond villain. He is, in many ways, so much more dangerous than that – he has the power of a fictional villain, but neither the plan nor the self-control. That could prove far more destructive than bad intent ever could.