Like many other countries around the world, mine has been struggling with US cuts to foreign aid. The current administration in the White House has a particular eye on South Africa, and president Trump issued an executive order cutting all aid to the country.

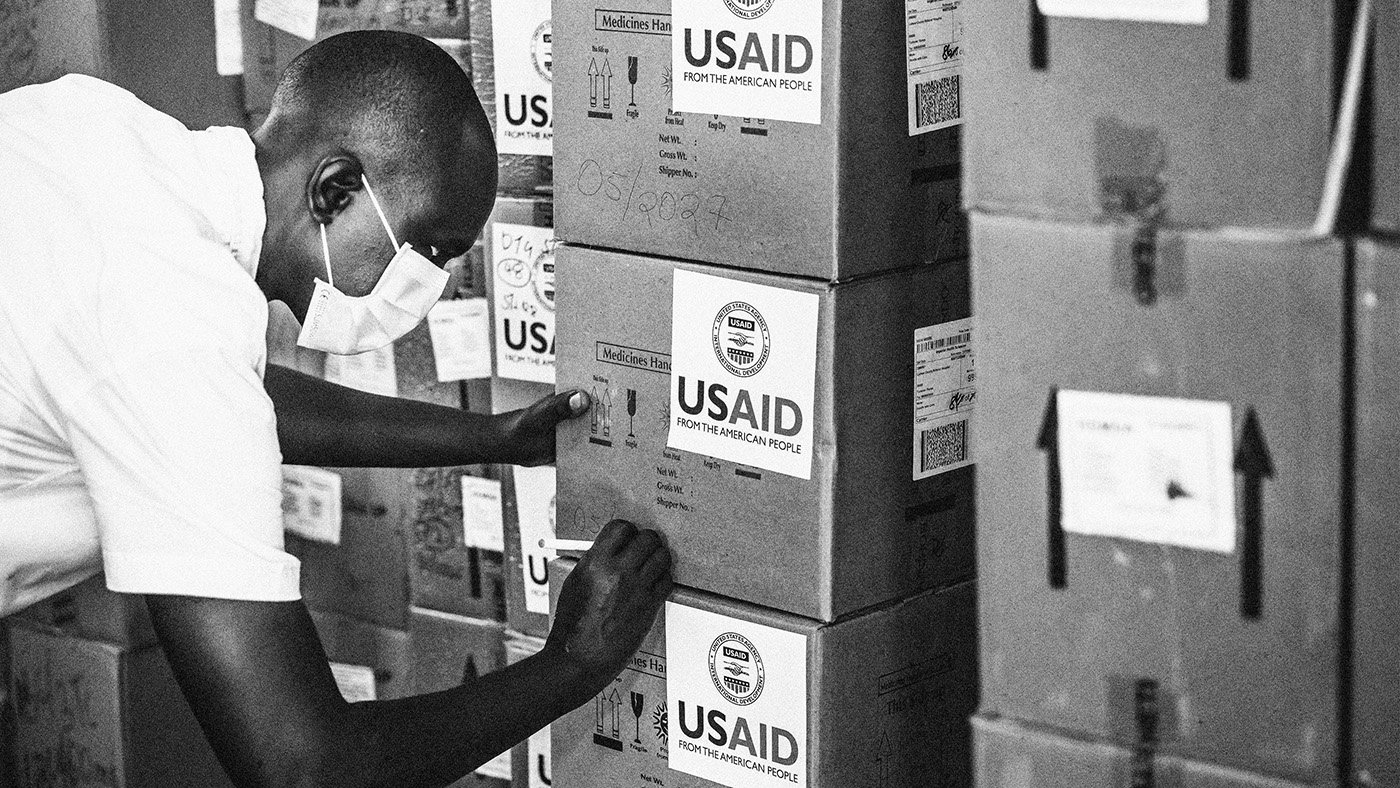

Trump’s aid cuts could force up to 5.6 million more Africans into extreme poverty in the next year. It will lead to millions more cases of malaria and childhood malnutrition. South Africa, as one of the key recipients of the US president’s emergency plan for AIDS relief and other health programmes, has been particularly affected in that area.

“We are expecting deaths.” This short and simple sentence from an activist in a webinar reverberates around my mind. The question of precisely how many deaths hangs in the air. If you do want to put a number to it, an impact tracker puts the estimated deaths from the Aids funding freeze at 31,740 for adults and 3,378 for children.

You can hardly be a health journalist in South Africa without covering HIV. We have the dubious accolade of having the most people living with the disease in the world. That, together with our relative stability, means we’ve had decades to build up a strong research base, and a system to prevent and treat the disease.

In the last months, I have been repeatedly driven to tears by the thought that this large, effective system is being forced to a halt. On one Monday afternoon in January, my inbox was filled with desperate pleas. “Come get your medicine quickly, while you still can!” Clinics catering to trans people, men who have sex with men, and other at-risk groups were given one day to shut their doors. After years of building up trust with vulnerable groups and giving out care, many of these clinics are now empty.

On the research side, years of work have been stopped, and researchers have scrambled to move their work elsewhere, even though the research itself is now often useless. The innovations, like possible vaccines and cures, that would have been a breakthrough for the whole world, are now hanging in the balance, and the research that might inspire them has no future. “Surely that can’t be right?” I am asked by friends and family. Aren’t there procedures and contracts? Yes, I say. There are. But it doesn’t seem to matter.

What strikes me as important and perhaps strategic is that not just the fruits of research and aid are being cut off, but the whole stem and plant that supported them. Any recourse the local workers may have wanted to pursue would likely have gone through the teams in the US that have been their trusted partners for years. But, often, these people and departments have been unceremoniously let go and are desperately confused themselves. There is seemingly no one to turn to.

For some insight that is less burdened with stories from those desperate or sick, I ask my partner, who is a journalist with a political slant, what he thinks. Trump campaigned on the slogan ‘America First’, and this intention is turning out to be rather linear, he says. Trump’s actions aren’t putting America first in terms of global aid or research, it is simply about keeping American money at home.

That pragmatic analysis has me falling into ideological rabbit holes of whether countries, particularly rich Western, historically powerful nations, should be giving aid to anyone. I’m no philosopher, but I do know that how the aid was pulled back is problematic, and people are suffering because of it.

Of course, there is always hope. When I write the endings of my stories about how resilient Africans are and how people are pushing beyond the devastating effects, I’m not being trite. There are strategies, court cases, and other opportunities being pursued. And that matters. But, as those expected deaths start ticking up -whether they are being seen and counted or not – it’s hard to believe that’s enough to stem the tide.