Perhaps because of recent commentary from tech billionaires, perhaps because of intriguing developments in quantum mechanics or perhaps because people are so unhappy with the state of the world these days, questions about reality and meaning seem to be everywhere.

Such questions were never ignored completely, but given the increasingly fantastical answers that people have been entertaining of late, this seems like a good time to reflect on what we know, what we can know and what we know to be impossible.

One way to answer these questions more systematically is to invoke the concept of an effective theory, which is the deep yet simple-sounding approach to reality that physicists have taken for years.

Effective theories employ what is measurable to make physical laws whose claims to applicability extend only over the regime that has been tested. Such theories make predictions and describe measurements while acknowledging the possibility of a more fundamental description of nature that might emerge when measuring devices and measurements improve.

That’s OK, because the most elemental description isn’t always the most enlightening. Particle physics posits that elementary particles are the core ingredients of nature. String theory takes this paradigm further to say that particles arise as oscillating fundamental strings. Both would agree that without the underlying presence of elementary particles, matter would not exist.

Yet even the most inveterate theoretical physicist would say this doesn’t mean that we can easily interpret everything in terms of those basic ingredients. Knowing music comes from oscillating atoms doesn’t tell us what music is. A music theorist would describe music very differently than an atomic physicist would. They are both correct, but they answer different questions that apply on different scales.

I find effective field theories comforting. They say that you don’t have to know all the answers in order to find meaning and make predictions that you can test. You don’t have to know about those more fundamental ingredients underlying what we see if you can’t detect any measurable consequences.

This is a way to think about almost anything – after all, we can’t say much about things we don’t even know are there. But physics goes a step further: it tells us that a theory isn’t necessarily complete when predictions fail, even by a tiny amount. A new theory can take over at a fundamental scale; it doesn’t negate the existing theory but shows how that theory is an approximation – albeit often a very good one for the range of interest.

For instance, Isaac Newton’s laws work well enough to send a man to the moon, but quantum mechanics and relativity are more fundamental laws of nature. We should keep effective theories in mind because new ideas will be consistent with that framework. You don’t have to drop everything you thought you understood about the world. And physicists still can trust their predictions. They might be approximations, but they are accurate enough to describe what we can currently observe.

This does, however, lead to a major insight: that small inconsistencies can reveal enormous underlying ideas. Those inconsistencies might be measurements that don’t quite agree with predictions, or they might be purely theoretical.

The fundamental description of reality isn’t necessarily just one single thing. Effective theories are indeed a source of comfort in this context amid our search for meaning. Even without knowing all the elementary components, and even though life, our planet, the solar system and the universe as we know it are all ephemeral, we can still think of the world as a relevant system and find meaning.

Indeed let’s remember that just as complex phenomena require fundamental particles for their existence, nearly eight billion humans require one world – ours – to survive. Whatever other realities might be possible, the work we do to create effective theories reminds us to treasure and preserve the beauty of the reality that underlies our existence today.

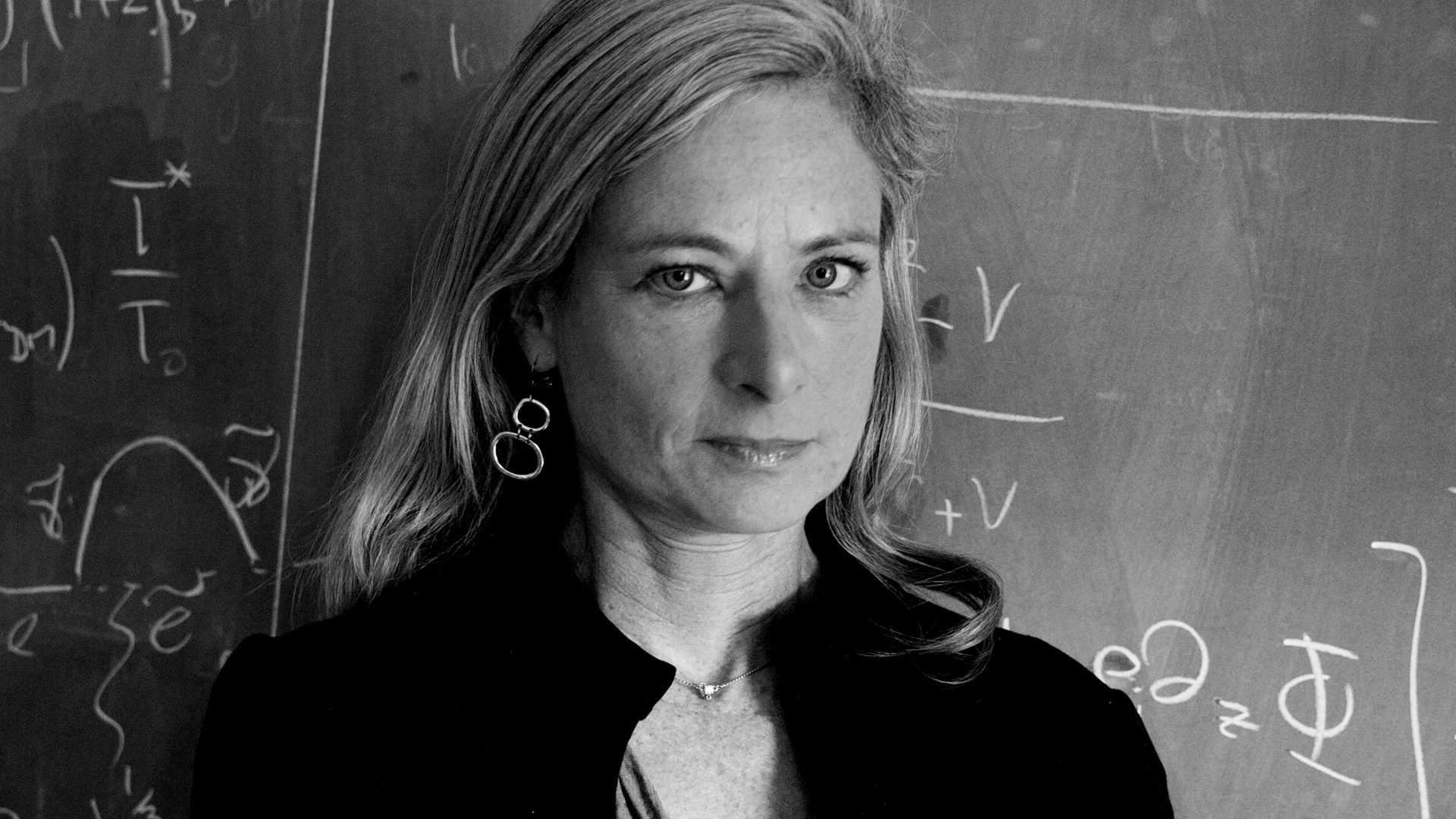

Lisa Randall is a theoretical physicist working in particle physics and cosmology. She is the Frank B. Baird, Jr professor of science in the physics faculty of Harvard University © The New York Times Company and Lisa Randall